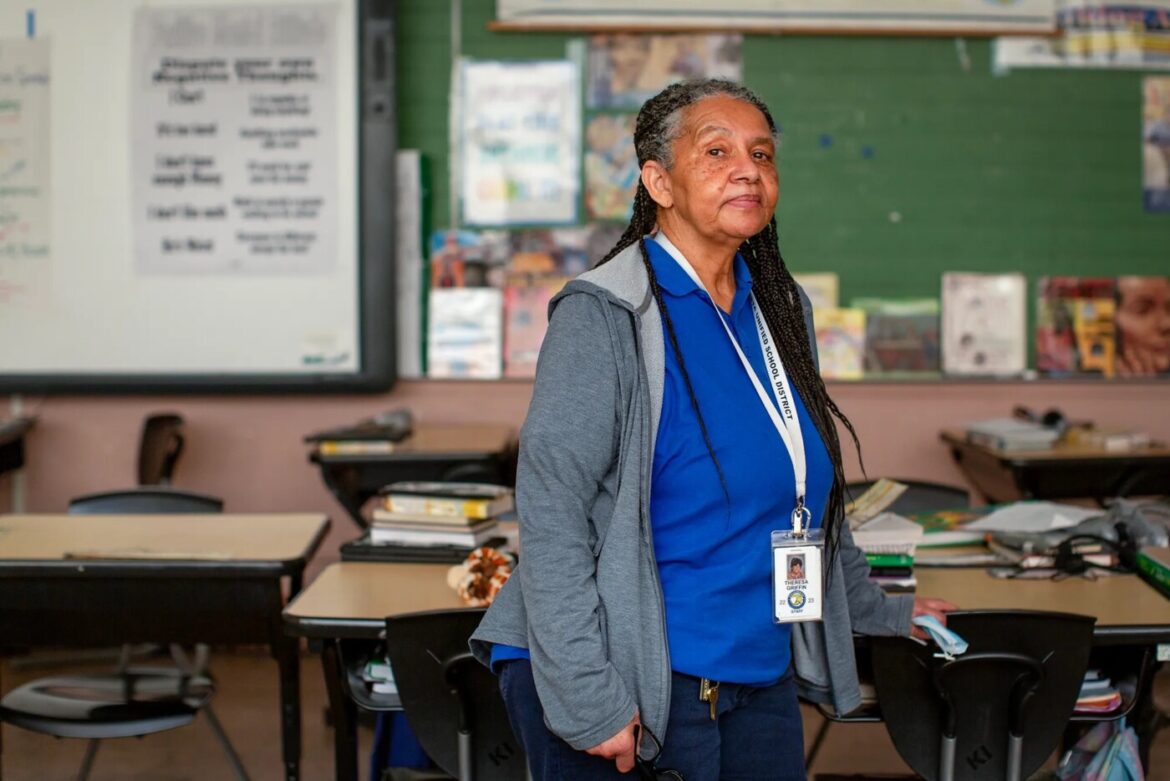

Halfway through a chilly school day in February, Theresa Griffin’s sixth grade classroom at Stege Elementary is more chaotic than usual. On the white board, Griffin writes the names of talkative students who will be staying behind after the lunch bell rings. A knock on the door interrupts reading instruction.

Six younger students need a classroom to work in while their teachers are attending a conference. Griffin spends 10 minutes rearranging tables to make space for them. Griffin is willing to do anything she can to help her colleagues — if she can offer a little support, maybe they’ll stick around at the school where many teachers leave after a few years. At the start of the current school year, Griffin was the only teacher at Stege with more than five years of experience — she’s been teaching at the school 23 years.

Located in Richmond just north of Berkeley, Stege serves the highest percentage of students from low-income households in the West Contra Costa Unified School District but its teachers on average have less experience than all but one other school. And that experience disparity isn’t unique to Stege and West Contra Costa — it plays out in schools throughout California.

The dearth of experienced teachers at high-poverty schools contributes to one of the defining traits of public education: the achievement gap between students from low-income families and their higher-income peers. At schools throughout California, standardized test scores plummet when poverty rates rise. Last school year, 47% of students statewide met English language arts standards and 33% met math standards. At Stege, those rates were far lower, just 11% and 9%, respectively.

Over the past several decades, solutions to teacher staffing disparities have swirled within California’s state Legislature, local school boards and among academic researchers. Chief among them: paying teachers more to work at high-poverty schools. But again and again, teachers unions have shot down that idea.

The unions’ opposition frustrates some researchers who point to the benefits of what’s called “differentiated pay.” But labor groups point to the complex and fragile ecosystem that can be disrupted by trying to address just one piece of the broader inequality plaguing public education.

The California Teachers Association codified its opposition to differentiated pay in its policy handbook, which explains that school districts use what is known as a “single salary schedule” to pay all teachers at all schools the same wages based on their experience and education levels. “The model is widely accepted because it is seen as less arbitrary, clearer and more predictable,” the handbook states. “Because of these factors, the single salary schedule will continue to be the foundation of educators’ pay.”

Claudia Briggs, a spokesperson for the association, said public school districts should not be using their limited pool of funds to pay certain teachers more than others.

“(Differentiated pay) can be very divisive and hard to implement fairly and consistently,” Briggs said. “And it doesn’t get to the root of the problem.”

In 2009, the statewide union assailed legislation authored by former state Sen. Darrell Steinberg that would have barred districts from laying off a larger share of teachers from high-poverty schools. School employees are typically laid off based on seniority, with newer teachers being most vulnerable. Steinberg said the state needed to step in to ensure that high-poverty schools could build strong teams of educators. The California Teachers Association argued for local control over layoffs.

“(The union) put up billboards saying I wasn’t friendly to education,” Steinberg said. “Some fights are just worth having.”

The union also rallied against merit pay in federal programs like Race to the Top that would have required districts to use test scores to evaluate teachers. Under pressure from the union, California lawmakers refused to implement a system of teacher evaluations, weakening their chances of winning a chunk of the $4 billion in competitive grants offered by the Obama Administration.

Briggs said differentiated pay is a “Band-Aid.” She added that paying higher salaries for teachers at certain schools is a decision for local districts and their unions, but the California Teachers Association opposes it as a statewide policy. State lawmakers should focus on raising salaries and improving working conditions for all teachers, she said.

In any conversation about improving teacher retention, union leaders, including those at the California Teachers Association, are likely to mention community schools as a more holistic solution. Community schools partner with local social service, mental health and other medical providers to link students and their families with the help they need. Union leaders say community schools can remedy the hardships facing students, rather than simply paying teachers more to single-handedly address the impacts of poverty.

“Paying higher salaries for hard-to-staff schools is a flawed solution,” Briggs said. “It doesn’t address the reasons they’re hard to staff in the first place.”

In 2018, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond told CalMatters during his election campaign that he believes all teachers should be paid more, and that the focus should be on improving working conditions. Thurmond said the studies on differentiated pay showed mixed results, specifically citing research by the Learning Policy Institute. One study by the research organization found that teachers at high-poverty schools were more likely to leave because of the pressures of standardized testing and unhappiness about their administrations, not compensation.

Thurmond, who won election and re-election with strong backing from the teachers union, wouldn’t comment for this story, but Deputy Superintendent Malia Vella replied on his behalf and made clear that his opposition to paying teachers more in high-poverty schools hasn’t changed. Instead, Vella said, the solution is raising salaries for all teachers along with smaller class sizes, more mentorship and affordable housing.

“A complex problem needs a complex solution,” Vella said. “Yes, raising salaries, but also doing all the things we know will make the system sustainable.”

Statewide snapshot

It’s a common pattern within the teaching workforce: young teachers begin their careers in high-poverty schools, put in a few years of service and transfer to a school in a more affluent neighborhood once they acquire a bit of seniority. Schools serving wealthier families tend to have more classroom resources, higher test scores and more involved parents. Teachers feel physically safer and more supported by their principals and administrators.

The result is a constant drain on schools with the neediest kids, which serve as training grounds for novice teachers.

CalMatters analyzed teacher experience data from 35 California school districts and 1,280 schools, including those from urban, suburban and rural communities. The correlation between student poverty and teacher experience is most obvious in large urban districts. In San Diego Unified, the state’s second-largest district, 17% of teachers at the 20 highest-poverty schools have less than five years of experience. At the more affluent schools, just 6% have less than five years of experience.

Staffing data from other large urban districts, including Long Beach, Oakland, and Sacramento, show a similar trend. These trends align with national research showing that high-poverty communities have the least access to experienced teachers.

The West Contra Costa Unified School District has 64 schools. Among them, the percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced-price meals ranges from 7% at Kensington Elementary to 77% at Stege. In 2022, Stege Elementary was identified as one of the 474 lowest-performing schools in the state.

The median years of experience among the 13 teachers at Stege, according to district data from 2022, is three years. Griffin is the one teacher in the school with more than six years of experience, and she believes her consistent presence makes a difference.

“When you have kids that come from families where they have a lot of strife going on, they don’t have anybody that is consistent,” Griffin said. “Children like to have consistency, and when you don’t have consistency they don’t know what to do.”

Experience is just one of the ways experts measure the quality of an educator. A teacher’s education level and effect on student test scores are also often factored in.

However it’s measured, there’s a large body of research showing that teacher quality is more influential than every other factor in a student’s education. That includes a student’s socioeconomic background, language abilities, school size and class size. At high-poverty schools, where students are more likely to be achieving below grade level, a quality teacher can make an even bigger difference. Andrew Johnston, an economist at UC Merced, said the research makes clear that an effective teacher can have a profound impact on all students.

“What’s amazing is that when we randomly assign a kid to a high-quality teacher, not only are they doing better in the years after that, but they’re doing significantly better in adulthood,” Johnston said. “A good teacher increases a student’s future earnings and decreases incarceration rates.”

The suggestion of differentiated pay triggers questions about whether money alone can entice the best teachers to work at the highest-needs schools. And that leads to the thornier question of which teachers deserve to be paid more.

John Zabala is the president of United Teachers of Richmond, the local union for West Contra Costa Unified. He was previously a school psychologist at another high-poverty school in the district. His experience has led him to support the idea of differentiated pay, but he knows that union opposition makes it untenable.

“I think we have to be open to things,” he said. “But I can already hear the teachers in other schools being upset that they’re not getting additional pay.”

Griffin also thinks teachers at Stege Elementary should be paid more, but she’s in it for the mission more than the money. She said teachers’ compensation is less important than their commitment to maintain high standards for all students. It’s a way of showing love to students who might not have anyone else who believes in them.

“I demand excellence, and I will help you get there if you’re willing to get there with me,” Griffin said. “But I’m very strict and sometimes that can be hard on them because they’re not getting that from anywhere else.”

Challenges at high-poverty schools

Griffin comes to school dressed in jeans and a blue polo shirt under a gray hoodie. After making copies in the front office, she walks in a steady gait down the long hallway to tidy her classroom before school starts. She declines to share her age, saying her students have been trying to figure out how old she is.

She speaks slowly in a soothing voice. As students file into the classroom, Griffin asks them to remove their hats and hoods. She delegates tasks to her students: one oversees the pencil sharpener while another distributes textbooks.

As students begin working independently on their iPads, Griffin takes attendance. From the corner of her eye she sees one student chewing gum.

“My trash can is lonely,” she tells him without looking up from the class roster.

Teaching students who live in poverty is uniquely challenging. They often come to school without having eaten breakfast or dinner the previous night, making it harder for them to focus and easier for them to be disruptive. Those experiencing homelessness or moving frequently have erratic attendance. Students with emotional traumas can require teachers to serve as both therapists and social workers.

“At some of the schools where I served, the way they treated kids of color was just horrible in my eyes,” said Griffin, who knows that Black and Latino students are more likely to be living in poverty. “They had very little expectations for their academics.”

At Stege, 44% of students are Black compared to 13% districtwide. Among them, 12% met or exceeded standards in English language arts and only 6% met or exceeded standards in math last school year.

Jeremy, a Black student in Griffin’s sixth grade class, said he likes how Griffin “does it old school.” He admits he’s talkative in class, and so he understands when she scolds him.

“She’s more experienced,” Jeremy said. “Other teachers get used. They get played because they don’t know how to control their students.”

Researchers say the benefits of experience usually plateau after five years in the profession, with the steepest learning curves occurring in the first three years.

The number of veteran teachers at a school can provide clues to the work environment as well as the job market in the surrounding community. Under most union contracts seniority must be considered when a teacher applies for a job, so more veteran teachers at a school is often an indicator of a less stressful work environment.

“When teachers at high-poverty schools get a couple years of experience, they tend to transfer,” said Dan Goldhaber, the director at the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research, which studied gaps in teacher quality.

In other words, high-poverty schools see more turnover, while schools in more affluent areas see more applicants for teacher vacancies.

Mary Patterson is a teacher at Longfellow Middle School in Berkeley Unified. With 62% of students qualifying for free or reduced-price meals, Longfellow has more than double the poverty rate of the other two middle schools in the district. Patterson uses the term “headwinds” to describe the challenges her students face, such as dealing with biases because they are Black or Latino or being from a low-income or a divorced family.

“Our job’s harder. It just is,” she said. “But we teach every kid we get. We’re not a school that complains about our students.”

Patterson wrote an article almost 20 years ago about reducing turnover among newer teachers. The piece examines how administrators often require newer teachers to teach more subjects, resulting in longer hours with less pay. Add a high-poverty student body to those working conditions, and you get a work life that’s unsustainable for many educators, Patterson said.

The salary solution

Over the years economists as well as education and policy experts have studied the benefits of compensating teachers more to work in more challenging environments. Some researchers say differentiated pay alone isn’t a sustainable solution.

“The term ‘combat pay’ has been used in a pejorative way to describe those pay schemes,” said Tara Kini, the director of state policy at the Learning Policy Institute. “But if it’s not paired with strengthening the working environments in those schools, then it doesn’t hold up in the long term.”

But experts agree that it’s one method of increasing retention at hard-to-staff schools.

“The papers that have come out recently say that pay flexibility is super useful to schools and students,” said Johnston of UC Merced. “What happens with rigid pay schedules is that the person who’s totally checked out is being paid the same as a person who’s being a real hero for students.”

In public school districts in California, administrators negotiate with local teachers unions to agree on a salary schedule, which determines how much educators get paid based on their education level and years of experience. Most, if not all, school districts post their teacher salary schedules on their websites.

Teachers know exactly how much they and their colleagues are earning. Union leaders say this transparency is partly an effort to reduce historical pay gaps for women, people of color and other marginalized groups. The salary schedule also helps cultivate solidarity among a teaching force: Educators know they’re all being paid fairly compared to their peers, union leaders say. This lays the groundwork for collective bargaining and teachers’ loyalty to their unions.

Union leaders contend that differentiated pay would undermine collective bargaining — that instead, all teachers deserve raises.

“I absolutely believe that if we had a way to get teachers who were more effective and assign them to (schools with poorer students), we’d be better off,” said John Roach, the executive director of the School Employers Association of California. “But the collective bargaining process does everything it can to avoid identifying teachers as being better than another.”

Trying to pay the best teachers more to work in high-poverty schools inches school districts toward an even more fraught conversation about evaluating teacher quality. Experts, teachers unions and policymakers have argued over how to assess teachers for decades. From one perspective, teachers who have a history of raising their students’ test scores are seen as more qualified teachers.

Researchers refer to this measure as the “value-added” score assigned to a teacher. Eric Hanushek, a Stanford University economist, championed this way of assessing educators starting in the 1970s.

“On average, standardized test scores have shown to be really important,” he said. “This is not the only thing that measures a good teacher, but it’s an important part.”

Opponents of the value-added model argue that a teacher’s effectiveness can vary widely from year to year depending on the types of students and various other social and economic factors outside the classroom.

One policy mechanism has been around for 10 years as part of an effort to close achievement gaps. California’s Local Control Funding Formula, which is the state’s system for funding K-12 schools, sends more money to districts for their foster children, English learners and students from low-income households. But the intended results of the formula can only be fully realized with differentiated pay, Hanushek said.

“If you aren’t allowed to use the money in the best way possible, the whole system is being undermined,” he said.

Hanushek also said districts should be able to use test score data to send their most effective teachers to the highest-poverty schools with more pay. This would allow districts to directly target the extra money they receive via the formula, giving in essence a pay bonus to lure the best teachers to work at those schools.

But without support from teachers unions, that notion remains a pipe dream. Districts instead rely on the personal passion and commitment of individual teachers to close the achievement gap.

“If you take (differentiated pay) off the table, there’s not a lot you can do to get really high-quality teachers into poor schools,” Hanushek said.

In California, school districts avoid value-added measures. District officials assess teachers through classroom observations, but tenure protections prevent disciplinary action based on low test scores alone.

Policies in other states suggest differentiated pay could make hard-to-hire positions more desirable and more competitive. In Hawaii and Michigan, districts enticed special education teachers with salary increases between $10,000 and $15,000. One study found that in Georgia, higher pay for math and science teachers reduced turnover by up to 28%.

Griffin, the teacher at Stege Elementary, said the district once offered a $10,000 stipend for teachers who committed to work at a high-poverty school for two years. But she said most teachers left after fulfilling that commitment.

Like the California Teachers Association, local unions are also calling for more community schools. Zabala, the union president for West Contra Costa Unified who supports differentiated pay, also believes the community school model is a crucial piece of the needed reform. Since 2021, California lawmakers doled out $4 billion in community schools grants. West Contra Costa Unified is guaranteed a total of $31 million until 2027.

“I don’t believe that a stipend or pay differential is sufficient,” Zabala said. “There also needs to be a change in how we conceptualize schooling.”

Meanwhile, West Contra Costa Unified’s teachers just narrowly averted a strike last month after negotiating a 7% raise this year and a 7.5% raise next year — raises that will apply equally to teachers at schools with the wealthiest and poorest student bodies. Zabala said these raises will be crucial for attracting teachers to all of West Contra Costa Unified’s schools, especially amid a teacher shortage. He said his bargaining team also asked for one-time $2,500 stipends for teachers working in high-poverty schools, but district officials rejected that proposal.

The situation looks dire at the district, as it needs to cut $20 million this year to afford those teacher raises. Zabala expects much of those reductions to come from after-school and mental-health programs at high-poverty schools.

But Griffin said she isn’t overly concerned. If anything, she’s indifferent to the threat of budget cuts. She said she’s going to keep doing what she has always done: focus on her students.

After her students leave her class at the end of the day, Griffin begins tidying up her classroom, picking up books and papers her students left behind. She admits she’s tired, but only because she’s a morning person and not because her students were especially rowdy that day.

“I think you just have to have it in your heart to do what you need to do to help the kids,” Griffin said. “If it’s not in your heart, it makes it harder to do.”