Entering a contentious debate over reading, Gov. Gavin Newsom proposes that districts base literacy instruction on decades of research known as “the science of reading” as the next step to getting all children reading by third grade.

In budget language, Newsom is calling for literacy experts to create a “literacy road map” that would emphasize “explicit instruction in phonics, phonemic awareness, and other decoding skills” in the early grades. They are among the fundamental skills grounded in scientifically based research.

The road map would signal to teachers, school boards and administrators that California will join other states favoring “structured” over “balanced” literacy and other approaches that spend little or no time on phonics. (See Sec. 58, page 123 of the proposed TK-12 trailer bill.)

But unlike other states, California imposes no requirements on districts regarding how to teach reading.

Each district can decide how and what to teach, even if they use ineffective strategies and curriculums that can set back whether a child learns to read.

Children with undetected learning disabilities or who enter school with little exposure to reading are especially affected. The literacy road map wouldn’t change that hands-off approach and therefore won’t make much of a difference, critics argue, until the state puts its leverage and resources behind it.

California’s literacy road map would be a voluntary, instructional guide. Other states, including Colorado, Mississippi, Tennessee and Connecticut, have created comprehensive early literacy plans as their literacy road maps. They require or incentivize districts to train teachers and adopt textbooks tied to the science of reading.

The decision to write a “road map” comes at a time when there is a push across the country in districts and states to improve literacy. Last year, only 42% of California’s third graders, the students most affected by distance learning and Covid disruptions, read at grade level. That’s down from 48.5% in 2019, although scores have stagnated for decades. Only 30% of low-income students were at grade level.

The initial reaction to Newsom’s proposal has been mixed. Advocates agree that it is important to emphasize fundamental reading skills, which also include vocabulary and reading comprehension, in statutory language and in an unambiguous, practical instructional plan. But they argue that Newsom’s literacy road map is a mile marker, not a route to effective instruction.

Efforts by the state so far “have been disconnected and haphazard,” said Arun Ramanathan, who is transitioning from CEO to senior adviser of Pivot Learning, an Oakland-based national nonprofit that works with districts on improving math and reading.

“A road map will be meaningful if it directs districts to utilize their funding to buy the right curriculums and supplemental materials and then train teachers in them,” he said.

Napa County Superintendent of Schools Barbara Nemko, a co-chair of State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond’s Task Force on Early Literacy, is more hopeful.

“I am a big believer in taking the first step. Right now we have nothing, leaving everyone on their own to do what they want,” said Nemko. “It’s good for the state to put out the notion that the science of reading is the right way. Given the opposition, this is a good place to start.”

Linda Diamond disagrees. “I see nothing in it that strengthens literacy instruction,” said Diamond, a retired executive of a California-based reading improvement firm who continues to track literacy legislation and teacher preparation programs across the nation. “No teeth, no accountability mechanism. In a local control state, it is just words. Districts will continue to pick and choose from a hodgepodge of resources.”

The road map will be more specific and practical, said Linda Darling-Hammond, the president of the California State Board of Education and an education adviser to Newsom. “Here’s what a literacy instruction block can look like based on what we know from the science of reading. Here is the way that you can organize reading, writing, speaking and listening, the resources you can access and break it down in very concrete ways grade by grade.” It will be distributed through county offices of education and others involved in the state’s system of support for districts and schools whose students are doing poorly in reading.

Shelly Spiegel-Coleman, a leading advocate for English learners, said she is pleased that the road map specifically calls for addressing English learners’ need to develop listening and speaking, and aligning with reading approaches for those students. “This is an excellent beginning,” she said.

Todd Collins, a Palo Alto Unified school board member and literacy advocate who founded the California Reading Coalition, said, “I’m sure that it’s good to make state guidance a little more accessible. But is that going to meaningfully change the way districts provide instruction? Are they going to buy foundational skill supplements and send all of their kindergarten-through-grade-two teachers to training to improve their grasp of foundational skills? I don’t think the road map is going to have much effect on that.”

Heather Hough, executive director of PACE, a California university-based research nonprofit, agrees. “A road map can set a vision, but structures must be in place to ensure it is implemented by collecting data and holding people accountable,” she said.

The state does not do that. It does not know which reading curriculums districts are using and how well students in TK to second grade are learning to read. It does not require districts to report a plan for reading improvement in those early grades to parents and the community as part of its main planning document, the Local Control and Accountability Plan, and then update them on progress.

“The upshot,” wrote Elliot Regenstein, a national early education authority, in a 2021 report, Building a Coherent P-12 Education System in California, “is that many districts do not really know how children are doing in those early years, and there is certainly no larger statewide sense of how young children are progressing.”

An underused reading framework

The road map won’t be the first time the state has cited fundamental reading skills like phonemic awareness, which is the ability to identify distinct units of sounds in spoken words, as essential. The 2013 English Language Arts/English Language Development Framework devoted sections to it, although the state did not promote or train teachers in the massive document. The 2021 California Comprehensive State Literacy Plan contained references as well, although that 150-pager was written to tell the federal government how California would support districts with their own local literacy initiatives, said Darling-Hammond.

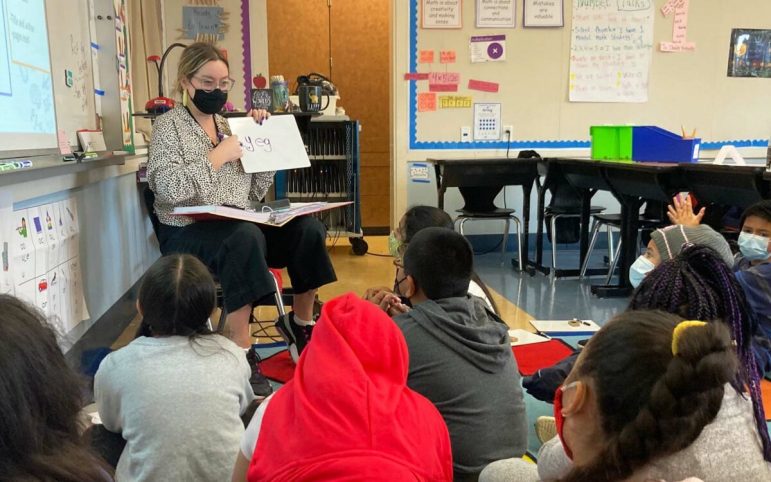

Leslie Zoroya, reading project director for the Los Angeles County Office of Education, said she looks forward to the road map. “If practical, it could be powerful,” she said.

“I hope it includes what teachers want to know,” said Zoroya, whose office trains teachers and district administrators in the science of reading through a $5 million federal grant. “What does quality evidence-based instruction look like? How do I use it when a curriculum is not aligned with the science of learning? How do I use assessments to identify skill gaps? The how is really important.”

Darling-Hammond said that the proposed literacy road map’s coherent set of best practices, with guidance on how to adopt them, is a critical next step to literacy improvement because the governor and Legislature cannot legally mandate curriculums under local control laws. Other local control states, like Colorado, work around mandates by funding only effective reading curriculums and textbooks from an approved list and training programs that teach the science of reading and explicit skills, like LETRS.

Influx of untrained teachers

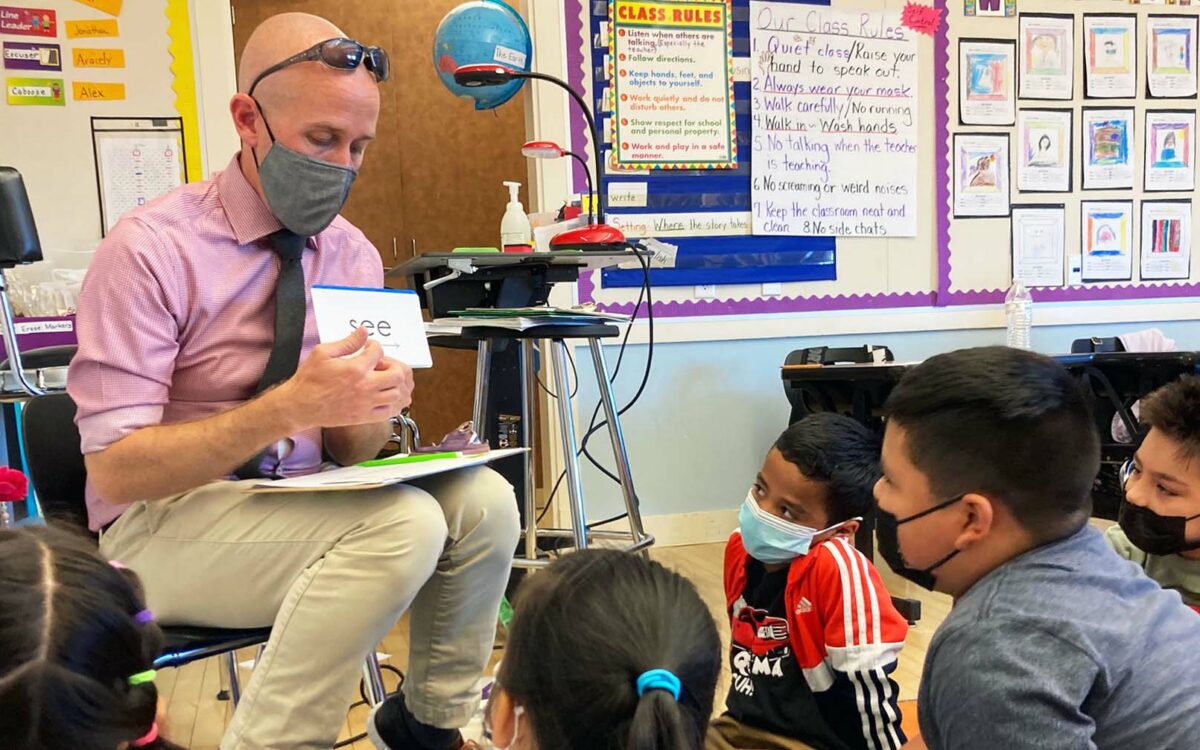

About half of new teachers during the past several years have not finished a teacher education program, Darling-Hammond said, and an increasing proportion enters with emergency credentials. Many are in low-income schools or small districts that may not have literacy coaches or reading specialists who can provide the reading training they lack.

“The literacy road map will be a tool that will be particularly helpful in these contexts, and hopefully we’ll make it clearer what the (English language arts) framework intends in terms of implementing the science of reading,” she said.

At the same time, starting in fall 2024, all teacher credentialing programs must begin instructing prospective teachers in new reading standards approved last fall by the Commission on Teacher Credentialing that are aligned with the science of reading. Candidates for a new TK-3 credential must learn the same standards.

As a result, two years from now, some new teachers trained in structured literacy will find themselves in “balanced literacy” districts that stress independent reading over sounding out words. They’ll be handed textbooks, like McGraw Hill Education’s Wonders and Benchmark Education’s Benchmark Advance, that conflict with the teaching skills they’ve just mastered.

A survey by the California Reading Coalition of 331 of the state’s largest districts found that nearly three-quarters used those two textbooks alone.

At the same time, the state will be increasing the number of literacy coaches and specialists trained in the science of learning, Darling-Hammond said. “We hope some of them will also bring more consistency and knowledge base to the schools where it may not have been.”

Recognizing that teachers’ access to effective literacy training “may be inadequate,” Darling-Hammond said the state is trying to understand the need.

Moving forward, she said, the literacy road map “may be a centerpiece” of future professional development “so that anyone who needs it can get access,” she said. It will be integral to the goal of achieving “uniformly strong instruction for everyone in every school.”

Missed opportunities

Earlier this month, Newsom issued a news release highlighting 10 “historic investments” in literacy, totaling nearly $10 billion, that California has made since he became governor “to support evidence-based policy changes and improve student literacy outcomes.” It was a political document in his continuing war of words with Republican nemeses in states like Florida and Texas.

“Instead of dabbling in the zealotry of whitewashing literature and banning books, California is making transformational investments to ensure our students can read,” he said, without offering evidence that dollars have been put to good use.

The list included some notable efforts: $28 million to empower parents with an early start to literacy by partnering with First 5 California; $25 million to the UCSF Dyslexia Center to create a multi-language tool to screen for learning difficulties, and $15 million to help 6,000 teachers receive a supplementary certification to teach reading.

But 90% of the money was in discretionary funding that districts could choose how to spend. It’s not clear if many districts, faced with a multitude of spending demands, have channeled money to improve reading — or would have, had Newsom and state leaders urged them to make early literacy a priority. They didn’t.

To Collins, the five-year, $250 million plan in the current state budget for literacy coaches for about 330 of the state’s highest-poverty schools illustrates the shortcomings in state policy.

Because the administration set no expectations for coaches or directives for instruction in the budget language, Collins predicts that “districts will spend mostly on more of what they have done that we know doesn’t work.”

Included in the appropriation is $25 million to train coaches, but eight months into the fiscal year, the California Department of Education has yet to solicit applications for a county office to run the program. And there’s no requirement that coaches in schools getting money undergo the training.

Newsom is proposing another $250 million in next year’s budget to double the number of reading coaches in more low-income schools. But the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office called it “premature to provide additional program funding” before knowing whether the first $250 million proved effective.

Ramanathan points to Connecticut’s literacy law, which allows districts to use state funding for materials and textbooks only if they buy from an approved list.

“A state’s power lies in incentivizing and guiding; that is typical outside of California,” he said.

As with state funding, districts directly received record one-time federal funding for Covid relief since 2020. The last and biggest installment of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund alone provided $15.3 billion and required that at least 20% go toward learning recovery. The money must be spent by the fall of 2024.

Covid funding presented a once-in-a-generation opportunity as well as relief. At best, state funding is projected to level off, if not decline, in the coming years.

However, many districts have not yet spent much of their federal learning loss money, Ramanathan said.

Referring to the road map, he said, “Better late than never.”