Assemblymember Megan Dahle ran to take her husband Brian’s vacated seat in 2020 and just last week announced that in 2024 she’ll be running again to take his place once he leaves the state Senate.

But she said it wasn’t her political significant other who gave her the initial motivation to pursue a political career.

It was a cinnamon roll: Her eldest son came home after school one day bragging that the cafeteria had given him a sugary pastry “the size of my head” that morning.

“That’s kind of how it started for me,” the Redding Republican said, referring to her 12 years so far in elected office. “I started going to the board meetings and listening and going, ‘Oh, I really should know more about this.’”

Those meetings convinced her to run for the Big Valley Joint Unified school board, where she eventually served as president. From there, she decided to run for state Assembly — reluctantly, she insists, because “she knew enough about” the Legislature via her husband to know what a slog it is as a Republican. Ultimately, she decided it was a good way to keep plugging away at education policy and other issues she cares about. And now she’s running for Senate.

She tells this story as a way to explain that nothing about her path in politics was the predictable result of her relationship to the man who ran for governor last year and was trounced by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

When she met Brian Dahle while he was campaigning for the county board of supervisors, she said she didn’t even know what that position was. She did not dream of becoming a politician as a kid. Nor did she come from a political family.

But she’s part of one now. And in the California Legislature, the Dahle clan is not alone.

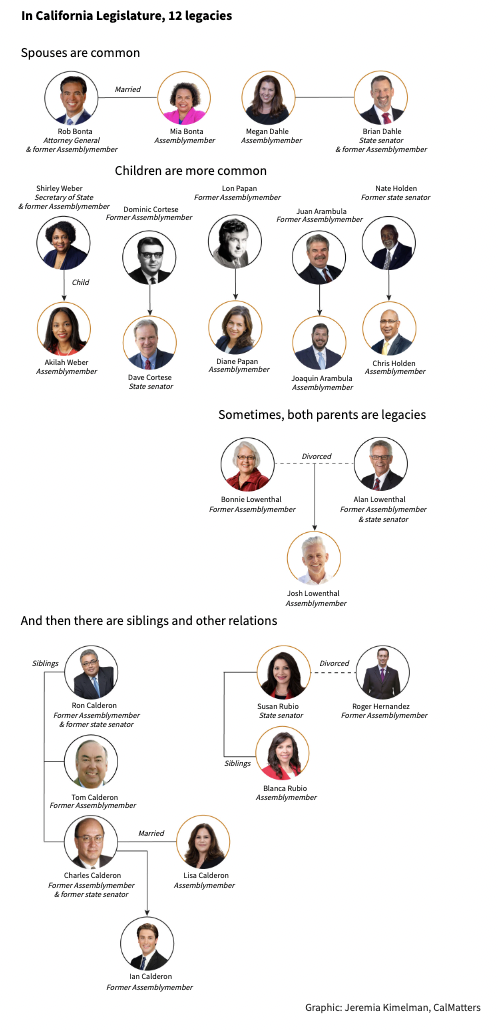

Of the 120 legislators, a dozen have current or former members in their immediate family. And the size of the Legacy Caucus may increase after the next election.

Assemblymember Dahle isn’t even the first family-connected candidate to launch a 2024 campaign.

Edith Villapudua, whose husband Carlos is a Stockton Democratic Assemblymember, is running for the state Senate. In late December, a day after Assemblymember Sabrina Cervantes, a Democrat from Corona, announced for state Senate, her sister Clarissa Cervantes, a Riverside city council member, announced that she’s running to take her place. And on Monday, San Diego County Supervisor Nathan Fletcher launched his state Senate campaign. He’s a former Assemblymember, but he’s also married to Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher, who served in the Assembly from 2013 until last year, when she left to run the California Labor Federation.

The fact that so many state lawmakers have fellow California pols in their family tree is no one-off. At least 10% of the Legislature has been related to at least one current or former state lawmaker since 2001, according to data compiled by Alex Vassar, a spokesperson for the California State Library and the unofficial keeper of legislative lore and trivia. His tally includes direct family ties, but also more distant kin, such as in-laws, nephews and great-grandchildren.

The last time the Legislature lacked a single family-tied member was 1910, according to Vassar.

What’s true of the Legislature may simply be true of politics in general. Adams, Bush, Clinton, Kennedy and Roosevelt are just a few of the most notable last names in American political history. An analysis of congressional family ties found that serving in the House of Representatives for more than one term increased the likelihood that an incumbent “will have a relative entering Congress in the future by about 70%.”

And in California, a Brown — be it, Jerry, his sister Kathleen or his father Pat — was on 15 of the state’s 18 statewide midterm ballots between 1946 and 2014, notes Claremont McKenna College politics professor Jack Pitney.

In the state Capitol, the omnipresence of political families can shape the culture — and, in the cases of relatives serving at the same time, the way that lawmaking is done.

At best, it provides a way for institutional knowledge to pass from one generation to the next despite term limits. At worst, it can provide fodder for cynics who believe that political power is only available to those who know the right people.

“The Nepo phenomenon is not confined to Hollywood,” said Pitney. “In any field of work, but especially politics, it helps to have family on the inside.”

What’s in a name?

There are a number of reasons why winning elections might run in the family. Exposure to the world of politics might inspire someone to follow in the footsteps of a sibling, spouse or parent. Connections and know-how could be bequeathed. If there’s such a thing as raw political talent, maybe it’s genetic.

State Sen. Dave Cortese, a Campbell Democrat, is quick to concede another reason: Name identification. His father, Dominic, served on the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors before nabbing a seat in the Assembly and, in the pre-term limit era, holding it for 16 years. That was a lot of time spent reminding voters of the “Cortese” name.

That came in handy when the younger Cortese launched his first campaign, for a seat on the East San Jose school board in 1992: “It’s me and a couple other people running, and I’ve got a name at that point that’s got 12 years of Board of Supervisors and another 12 years of state Assembly recognition in the area, right? I mean, that’s name ID that goes from ’68 to ’92.”

In another study of congressional elections, University of Pennsylvania professor Brian Feinstein estimated that “dynastic politicians” get a 4-percentage-point electoral boost on average, thanks solely to their connection to a previously elected family member. Feinstein called this effect the “brand name advantage” to distinguish it from “capital advantages” that might come with being related to a politician — a working understanding of how to put together a campaign, seek endorsements or raise money.

Cortese said he got a bit of that from his dad, too.

As an 11-year-old helping out on his dad’s first supervisorial campaign, he said he fell in love with precinct walking and canvassing at the county fairgrounds. Twenty four years later, he said he “tried to sort of mimic that process.”

And though he said his father did nothing to either persuade or dissuade him from getting into politics, Cortese recalled that he did give him one valuable piece of advice: “Just make sure that you’re reaching out to the right people.”

‘Good training’

Diane Papan, a San Mateo Democrat elected to the Assembly last November, remembers getting a similar early education in retail politics from her dad, the pugnacious Lou Papan, a former Assemblymember who served as an “enforcer” for Willie Brown during his reign as Assembly speaker.

She recalls stuffing envelopes and knocking on doors, watching her father joke and glad-hand his way into the good graces of constituents and fellow lawmakers, getting a better-than-average fifth-grader’s schooling on how a bill becomes law and lobbying her father at the kitchen table to vote her way on certain legislation.

“Good training,” she said.

For many years of her childhood, Papan said that working on her dad’s campaigns was also one of the surest ways to spend quality time with him. And after a decade hiatus, when her dad ran for office again, she and her future husband were called to go knock on doors again.

“Running for office is a family affair,” she said. “It really does take the family buy-in.”

While Papan said her father instilled in her an early love of politics and policy making, she rejects the idea that it put her in the Legislature. California’s current crop of lawmakers is full of former staffers and the trusted friends of former lawmakers. A family tie is just one other kind of connection, she said.

Plus, Papan said she faced her own hurdles, as a female candidate. “Here’s where I get on my soapbox a little: It’s a lot easier for a man to be a chip off the old block,” she said.

Not that being a chip off of anyone’s block is a guarantee of anything.

Papan’s sister, Gina, a Millbrae city councilmember, has run for the Assembly twice with no success. Last year, Daniel Hertzberg ran for his father Bob’s Senate seat in the San Fernando Valley, but lost despite racking up a formidable list of endorsers and financial backers. And in 2020, Sylvia Rubio, sister to current Assemblymember Blanca Rubio and state Sen. Susan Rubio, lost her bid to replace outgoing Assemblymember Ian Calderon.

Rubio’s loss was no renunciation of family ties in politics, however. The victor was Lisa Calderon, the outgoing incumbent’s stepmother.

Family values

More so than almost any member of the current Legislature, Assemblymember Josh Lowenthal, a Long Beach Democrat elected last November, would seem to fit the description of a dynastic politician. Both his parents, Alan and Bonnie, served in the Assembly. His father went on to the state Senate and finally to Congress, before he retired last month. The Assemblymember’s brother, Daniel, is a superior court judge.

But unlike Cortese and Papan, Lowenthal does not point to warm childhood memories of the campaign trail as a source of inspiration. His parents didn’t launch their political careers until both sons were adults. And Josh Lowenthal was technically the first in his family to win an election as student body president in 1989.

Lowenthal notes all this to make the point that in his family, politics is “more about values” than a pre-trodden path.

Before his parents ran for office, the Lowenthals were local activists, and he spent his childhood getting carted to protests and sit-ins. He regularly came home from school to find a living room full of community organizers, but a kitchen without table grapes (out of solidarity with United Farm Workers).

“My brother and I were certainly encouraged to be aware of the world around us,” he said. But they weren’t pressured to go into public service of any kind — certainly not into electoral politics. Lowenthal said he made that choice on his own after the election of Donald Trump as president in 2016.

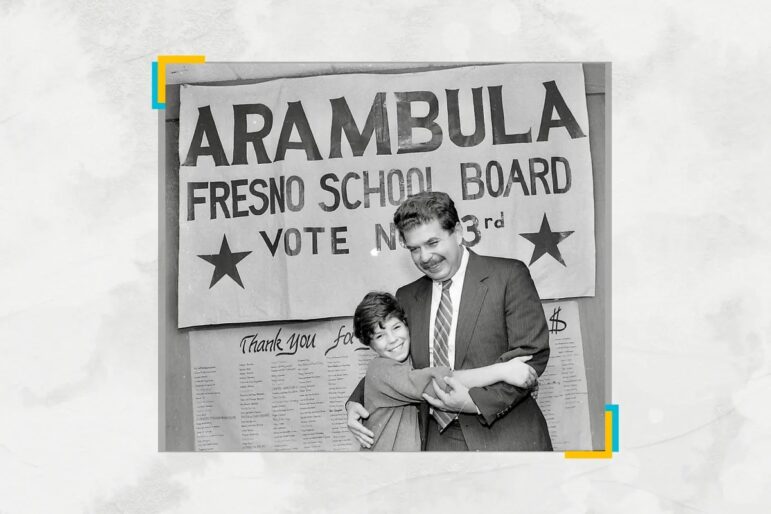

Assemblymember Joaquin Arambula, a Fresno Democrat, said there was no dynastic master plan in his family either. His father actively discouraged him from following him into politics, he said.

When he told his father in 2016 that he planned to interrupt a stable and lucrative career in emergency medicine to run for a vacant Assembly seat, Juan Arambula, who represented the same area from 2004 to 2010, waged a six-month campaign to persuade him to pass on the opportunity.

“He was trying to be a little protective, as fathers are supposed to be,” he said.. “Having understood what it takes to be in elected office, I think he really tried to talk me out of it.”

Dynamic duos

Most of the lawmakers interviewed for this story gave at last partial credit for their political careers to the family members who came before them. Then there’s Sen. Rubio, who gives her older sister Blanca all the credit.

“I say (to her) ‘I’m here because of you, whether it’s good or bad,’” she said. “She owns it.”

Assemblymember Rubio is happy to accept. The self-proclaimed “responsible” one who still brags of beating up her younger siblings’ school yard bullies, she said she first noticed the open position in Baldwin Park city government that launched her sister’s electoral career.

The conversation, as she recalls it, was succinct: “I was like, ‘Let’s run you for city clerk,’” and she was like, ‘Okay.’”

Blanca Rubio said her plan to engineer a modest political dynasty was born of frustration. The Rubios came to California as kids from Mexico and spent much of their childhood riddled with insecurities.

They were undocumented, self conscious of their accents and condescended to by teachers, she said. Their parents assumed that politics was a rarified sphere for people like the Kennedys.

But when Assemblymember Rubio won a seat on the local water board, it was a revelation to see the caliber of people already on the inside, she said.

“I was like, ‘That guy’s dumb,’” she said. “Just by knowing that that guy was dumb and he could do it, (we knew) we could totally do this.”

Now that both are in Sacramento, the sisters share a sense of vindication. But it’s their parents who might better appreciate the magnitude of the accomplishment, said Sen. Rubio. She chokes up when she recalls her parents’ visit to the Capitol to witness their daughters’ first joint inauguration.

“He was standing in front of this beautiful white building, he just looked up and he was crying and said, ‘Beyond my wildest dreams.’”

The Rubio sisters have found that serving with a family member also has its perks. By accompanying one another to various social events, they can more easily network with legislators in the other chamber. And if either have any difficulty persuading a lawmaker to introduce one of their bills, they each have “automatic jockeys” on the other side.

“I know that if I can’t find anybody I can, you know — I’m the oldest, I’m gonna make her take the bill,” the Assemblymember said.

Family benefits

Brian Dahle said it was particularly helpful to have his spouse in the Legislature last year when he was challenging Newsom. “The governor’s probably not going to be inclined to really do a lot to help me out when I’m poking at him, so Megan did more of the heavy lifting on her side and we were still able to get things done,” he said.

Even legislators with relatives who are no longer serving sometimes find their family connections to be useful.

Assemblymember Mia Bonta, an Oakland Democrat, was elected to replace her husband Rob in the Assembly after Newsom named him attorney general in 2021. The two still often work together; she introduces legislation sponsored by her husband’s office.

Sen. Rosilicie Ochoa Bogh, a Rancho Cucamonga Republican, said that after she told her husband’s cousin Russ that she planned to run for Senate in 2020, the former Assemblymember who briefly represented the Beaumont area in the early 2000s, pulled out his Rolodex. She said he’ll still pick up the phone if she’s looking for a veteran’s advice.

And when Cortese came to the Capitol as a senator that same year, he found that his dad, then in his late 80s, could still open doors for him.

“All of a sudden, I started having people come up to me — and it still happens every week, sometimes, multiple times a week — saying, ‘I know your father,’” he said.

Some will say it “straight out.” Others only hint at it. But Cortese said he often hears some version of the same message: “You’ve kind of got a legacy to uphold here.”