Brandon Yung was 16 years old when he realized that most American cities weren’t designed with people in mind. Without a car to go from place to place, the urban sprawl of his south Pasadena neighborhood outside Los Angeles left him feeling isolated.

Yung would spend the next few years attending activist meetings in Downtown LA and absorbed in online urbanist communities before enrolling at UC Berkeley in 2018. Facebook groups such as New Urbanist Memes for Transit Oriented Teens helped mitigate his growing discontent for the miles-long distances that separated him from his hometown.

But in some ways Berkeley was a revelation for Yung, whose Pasadena neighborhood had best served those who had the means to afford a car.

“Prior to Berkeley, I never lived in a place I would describe as walkable,” he said. The ability to quickly walk from the grocery store or the gym shortly before class was a defining moment in Yung’s understanding of city planning.

This realization — among others — came to a head during Yung’s senior year in 2021 when he and classmate Sam Greenberg co-founded Telegraph for People, a student organization dedicated to eliminating cars on the first few blocks of Telegraph Avenue. The immediate impetus for TFP was creation of the Berkeley Southside Complete Streets Project, a plan spearheaded by the city to improve road conditions along Telegraph Avenue, Bancroft Way, Fulton Street, and Dana Street. The goal of that plan was making it easier to walk and bike, but TFP proposed going a step further and banning cars.

The coronavirus pandemic had accelerated car-free campaigns across the country when cities began closing some streets to allow outdoor dining. The growing interest in walkable streets also reflected safety concerns as pedestrian fatalities nationwide hit a 40-year high in 2021.

During his final semester at Berkeley, Yung helped organize a march from campus to Telegraph, where about 100 students shut down traffic for hours.

In the following academic year, data science student Rebecca Mirvish succeeded Greenberg as TFP leader, and the group was recognized as a formal organization. It sponsored another rally to support Bay Area Transit Month, and it is now working to turn a slip lane area at Telegraph Avenue and Dwight Way into a plaza and the outdoor parking in front of Durant Food Court into a parklet.

Movement stalled, but not in park

Today, efforts to eliminate car traffic from part of Telegraph Avenue have stalled, but not without having made some progress. In February 2022, Berkeley City Council unanimously approved a plan spearheaded by council member Rigel Robinson to raise the street to sidewalk level, slowing traffic and giving pedestrians more space to walk between Bancroft and Dwight Ways, and to implement a designated bus lane. While TFP advocated for a more progressive plan to eliminate all personal vehicles, the decision from the City Council was seen as a victory and a step in the right direction. Yet, costs for the redesign exceeded the city’s and Robinson’s expectations, putting a temporary halt to the repaving project until more funding arises.

For Mirvish, this isn’t necessarily a problem. As TFP president, she plans to broaden the scope of the organization to encompass safe streets activism as a whole. Without its original founders and with a wrench having been thrown in the group’s flagship priority, the goal is to tap into student energy for pedestrianized streets through other projects.

“My biggest priority is making sure that we’re sustainable,” Mirvish said. “We want this to be something that can last a while.”

Mirvish is high-spirited and has a clear enthusiasm for urbanism. She hosts city council “watch parties” in her apartment on Tuesday nights and recently organized an end-of-semester social to San Francisco for members to ride the new Central Subway that opened on weekends in November. These efforts are a precursor to other activities she hopes to introduce next semester to make safe streets activism engaging for participants.

“By building community in TFP and with the surrounding community and city of Berkeley, I think that’ll also lead to longevity of the club,” she said.

According to Mirvish, there’s a clear through line between car-free streets and community. It’s this connection that she seeks to make apparent through community-building efforts within Telegraph for People. And the group is attracting new adherents.

“I definitely feel lucky that I found TFP and have made meaningful connections,” said Bryan Rodriguez, a junior transfer student from Oxnard who studies political science. Rodriguez found out about the group through Instagram and promptly joined in the fall. He credits Telegraph for People for acclimating him to campus as a new student and learning about transportation in the broader Bay Area.

“TFP does a great job of informing students on local government,” he said. “I look forward to continuing with the organization.”

TFP has roughly 200 general members and 5,000 followers across its social media platforms, exhibiting a growing popularity among young transportation enthusiasts online and across the Bay Area.

Driving forces of change

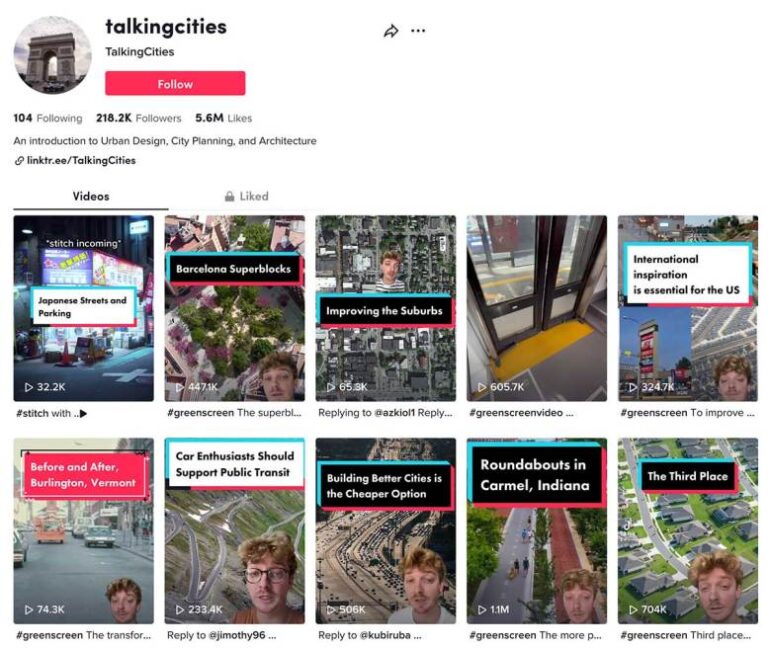

Urban planning has seen a rise in popularity among young adults in the last few years as an unexpected offshoot of pandemic-era regulations. Sparked by street closures across the country, the extra space made for socializing and outdoor dining was appealing to many and led to permanent car-free changes in numerous places, from John F. Kennedy Drive in San Francisco to open Fifth Ave. in New York City. Social media, too, raised teens’ and 20-somethings’ awareness of pedestrian-friendly city design through popular channels like Mr. Barricade and TalkingCities on TikTok. In some ways, Telegraph for People represents Gen Z’s both burgeoning fascination and frustration with America’s car-dependent cities.

“One of the silver linings of the pandemic (is) that we thought about our streets,” said Susan Handy, an Environmental Science and Policy professor at UC Davis.

Her research focuses on transportation and auto dependency. She believes that social media in particular “doesn’t hurt” in terms of getting young adults to begin thinking about other modes of transportation besides cars.

Gen Z members are also driving less and obtaining their licenses at lower rates than ever before. According to data from the Federal Highway Administration, 67 percent of 18-year-olds in 2004 had a license, compared to 58 percent in 2020. Handy states the reason for this is multifaceted, noting cultural and financial factors as potential forces.

“Kids are probably less interested in driving for cultural and prestige reasons,” she said, acknowledging that the social clout car ownership has historically bestowed on students has waned over the last few decades. However, “the reasons are also going to differ by community,” as some can’t afford to drive or have parents who are hesitant to put them behind the wheel.

Handy believes that this trend can only be seen as something positive, though, as research has shown that the longer amount of time teens and young adults spend without a car, the more likely they are to gain experience using other forms of transportation such as biking or riding the bus. Gen Z’s capacity to build a stronger “transportation literacy” will determine their level of car-dependency in the long-run, according to Handy.

“The research suggests that maybe [young people driving less] is not as lasting and as dramatic a change as we think,” she said, and that permanent shifts remain to be seen.

Accelerating car-free conversation

But TFP itself is inspiring similar groups elsewhere. At Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, for example, undergraduates Jesse Edelstein and Roni Wine hope to turn the main commercial corridor near campus, Thayer Street, into a car-free haven with the Brown Urban Mobility Project.

Wine stated that his inability to walk around the city to run errands after moving from Brazil is what piqued his interest in safe street design. For Edelstein, it was the little attention paid to roadway safety and infrastructure. “But we also understand the climate implications of a world dominated by sprawling, car-dependent cities and we want to join in the advocacy effort to confront that,” he said.

“Our goal is to accelerate conversations about car-free urban spaces so as to open people’s minds to how much quality of life they can gain from living in a city designed for people, not cars,” Edelstein said. “It is not easy to get to different parts of the city without biking on multiple-lane, high-speed roads.”

Although the project is in its early stages, the Brown students hope to replicate similar outreach efforts by TFP through a heavy social media presence and campus activism.

“We also really like how they incorporated fun into the organization’s day-to-day activities to keep the community united and active,” said Edelstein.

Still, if there’s any place in the country where a car-free future should materialize, it’s Berkeley. The city’s rich history of progressive activism makes it fertile ground for radical safe street design.

Even there, it isn’t easy. From funding issues to pushback from businesses fearful of what a redesign could mean for their retail sales, TFP faces an uphill battle.

Brandon Yung, though, remains optimistic. Now an analyst for the California Department of Housing and Community Development, he understands TFP’s purpose to be larger than the current policy disputes with the historic avenue.

“[TFP’s] number one purpose is to get people involved,” he said. “It doesn’t take itself too seriously … the whole Telegraph thing is inherently fun … it’s very Berkeley.”

Yung, who still lives in Berkeley, primarily gets around by walking or biking. Dishes clank in the background as he cooks dinner during a phone interview. The way he perceives it, TFP is an extension of the environmentalism movement with its core premise co-existing alongside green, sustainable modes of transportation. And, at the same time, it’s a project that mandates envisioning a future built upwards — one that is filled with greenery, quirky shops, and plazas.

“I think that young people are frustrated that environmentalism is built on a movement of saying ‘no,’” he said. “This is the forefront of trying to articulate an environmentalist movement premised on imagining and building rather than rejecting.”