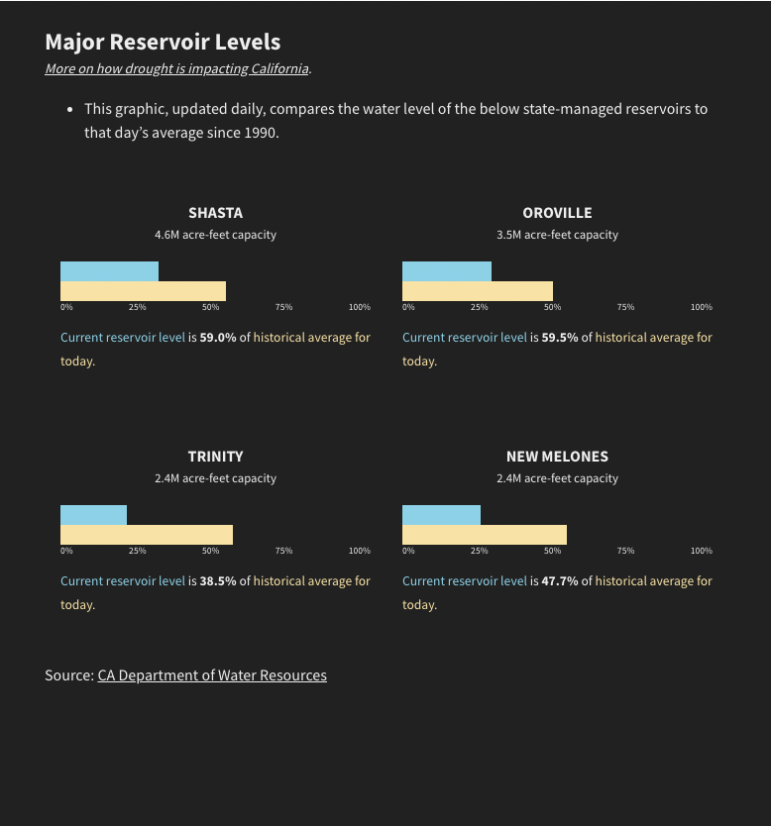

December has delivered a powerful punch of storms to California. But the wet weather comes with a dry dose of reality: The state’s largest reservoirs remain badly depleted, projected water deliveries are low, wells are drying up, and the Colorado River’s water, already diminished by a megadrought, is severely overallocated.

Throughout California, urban water managers are bracing for a fourth consecutive drought year. Nearly one out of every five water agencies — 76 out of 414 — in a recent state survey predict that they won’t have enough water to meet demand next year. That means they are likely to impose more severe restrictions on customers, with some Southern California providers considering a ban on all outdoor watering.

While December’s rain and snow show promise, water managers remember the same thing happened last year — epic early storms followed by the driest January through March in California’s recorded history.

“We’re not counting any chickens just yet,” said Andrea Pook, a spokesperson for the East Bay Municipal Utility District, which delivers water to 1.4 million Bay Area residents. The district’s water supply is in relatively good shape, with a 9% water deficit projected through the first half of 2023.

Last week the state announced an emergency regulation extending its ban on “wasteful water practices” through 2023. Included are watering while it’s raining, running decorative fountains without recirculating flows and washing vehicles with hoses not fitted with automatic shutoff nozzles, among others.

Some regions of California have more water than they need. Sacramento reported a 173% surplus for 2023 to state officials. City spokesperson Carlos Eliason said Sacramento has a healthy system of community wells to draw from in addition to the Sacramento and American rivers.

The Humboldt Bay Municipal Water District, serving 90,000 people in and around Eureka, reported an 834% surplus for 2023. Its main reservoir typically fills to the brim every year.

“Unfortunately, our system isn’t connected to other systems, so we can’t do anything to help our neighbors in other parts of the state, but we’d like to,” said General Manager John Friedenbach.

Other areas will probably cruise through the drought with some basic conservation efforts. The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission reported a 5% shortage for 2023 and the Santa Clara Valley Water District, serving the South Bay and Peninsula, has a shortfall of 11%.

Sonoma County’s major reservoir was at just 39% of capacity last week, its lowest level ever recorded, but Don Seymour, the county water agency’s deputy chief engineer, said there is no reason to panic. “That’s still a lot of water,” he said. “We could stretch that out into the spring of 2024.”

But other regions of the state — mostly in Southern California — aren’t as fortunate. Millions of Southern Californians will likely face outdoor watering restrictions or even bans, with probable exceptions made for the hand-watering of trees.

The Las Virgenes Municipal Water District, for instance, expects a 63% shortage based on average historical demand. The district serves 77,000 people in Agoura Hills, Calabasas and other nearby communities in western Los Angeles County.

“That means that if a household normally uses 100 gallons of water, we’ll be able to deliver 37 gallons,” said Las Virgenes’ public affairs officer Mike McNutt.

The district purchases between 20,000 and 25,000 acre-feet of imported water annually from the region’s wholesaler, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. This year that delivery could drop to 11,000 acre-feet, according to John Zhao, the district’s director of facilities and operations.

McNutt said residents have already cut water use by 35% from pre-drought levels, mostly from outdoor conservation. Most homes in the region, he said, are fully outfitted with high-efficiency appliances, toilets and showerheads. That means there is limited room to improve without more drastic action, which the district hopes to avoid.

But if drought conditions continue, Las Virgenes customers could be hit with a total outdoor watering ban in 2023 — a step up from the region’s one-day-per-week allowance implemented last spring by the Metropolitan Water District.

Las Virgenes has a 10,000-acre-foot reservoir to fall back on, and McNutt said the district may also seek transfers of water from nearby communities with water to spare — arrangements he said would have to be negotiated through the Metropolitan Water District.

Most Southern Californians — 27 million people — rely at least partially on the State Water Project, a system of dams and canals that moves water from the Sacramento Valley to Southern California. On Dec. 1, the Department of Water Resources announced it will initially allocate just 5% of the supply that water districts requested from the state — bad news for those with no other water source.

“We are 100% reliant on the State Water Project,” McNutt said.

The Ventura County communities of Thousand Oaks and Simi Valley face a similar dependency on the State Water Project.

“We wouldn’t exist without that imported water,” said Wanda Moyer, Simi Valley’s water conservation coordinator.

Simi Valley is expecting a 68% shortage in 2023 and will implement a total outdoor watering ban if the state’s delivery projections don’t improve, Moyer said.

In June, when Metropolitan’s once-weekly watering limit for gardens and lawns took effect, “people were angry,” she said.

Breaking the rules triggered a warning the first time, then fines. Next year, Simi Valley’s repeat offenders may face a tactical measure – the use of water restrictors.

These tools are basically washers with a hole in the center. Inserted inside a pipe, a restrictor allows just a trickle of water to pass. Las Virgenes has been using them since June on repeat water-use offenders. The district, which has installed more than 200 restrictors, keeps the device in place for two weeks before removing it, McNutt said. If violations continue, it’s reinstalled for three months, he said.

Moyer said scofflaws whose water pipes are fitted with restrictors “will be taking a military-type shower.”

Water connections serving non-residential sprinklers for lawns and other landscaping could be shut off completely, she said, following multiple violations.

Fort Bragg, on California’s North Coast, nearly ran out of water in 2021, forcing management into a stage 4 “water crisis” mode. A small desalination unit, capable of processing 200 gallons per minute, was revved up to meet basic needs for the 7,500 local residents. Meanwhile, outlying communities, like the seaside bluff town of Mendocino and isolated inns, restaurants and homes, saw wells run dry. Fort Bragg delivery trucks, carrying water provided by the city of Ukiah, brought relief.

Things have improved for Fort Bragg. In 2022, late spring rains recharged its reserves, said John Smith, the city’s director of public works. Its small reservoir is brim-full, and the desalination unit is ready to go if needed.

The city asked residents to use 20% less water, which they did — plus some.

“We asked for 20%, and they conserved 30%,” he said.

Earlier this year, Californians were slow to respond to drought warnings. In fact, their usage went up last spring. Californians emerged from the driest January, February and March on record with the biggest jump in water use since the drought began: a nearly 19% increase in March compared to two years earlier.

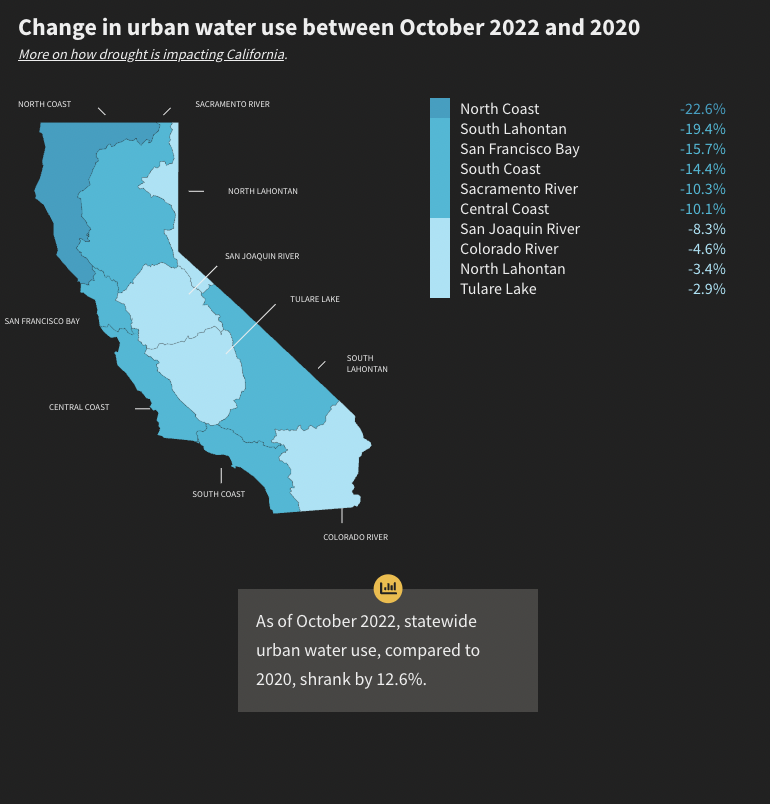

But many Californians have stepped up since then. In October, statewide urban water use dropped 12.6% compared to October of 2020.

Still, the cumulative savings (only 5.2% compared to 2020) fall far short of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s request for a 15% voluntary cut.

Santa Rosa’s water director, Jennifer Burke, said water use in the city of 180,000 is down 18% of average since June of 2021, thanks in part to rules limiting outdoor watering to nighttime hours when evaporative losses are less.

In Sacramento, residents have curbed water use by more than 20% by limiting residents to watering twice weekly from March through October and once per week the rest of the year. This ordinance, Eliason said, is permanent.

“We wanted to make sure water conservation is a way of life,” Eliason said.

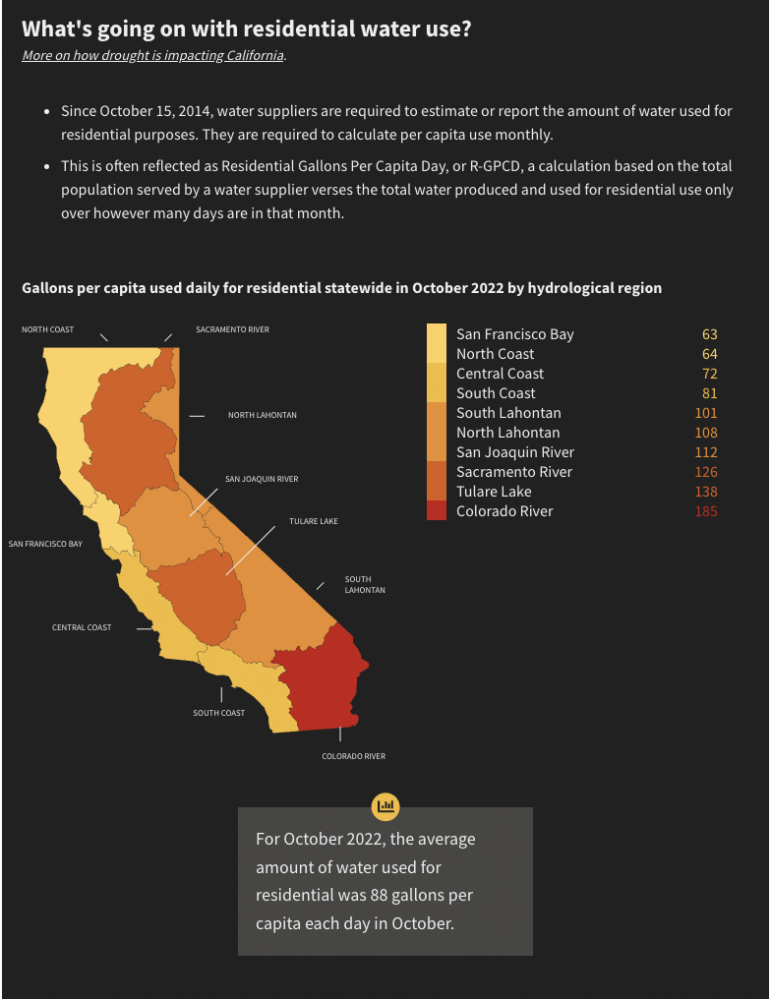

For many Californians, it already is. The state’s residents have streamlined their water use and reduced waste for decades. Daily residential water use statewide in October decreased to 88 gallons per capita, compared to the five-year average of 97.

Jeffrey Mount, a senior fellow with the Public Policy Institute of California, said California’s overall water consumption has remained the same since the 1980s even though the population grew from 30 million to 40 million.

“That is a good indication that adjustments can be made as things get drier,” Mount said.

An even steeper trend toward conservation has been logged by the East Bay Municipal Utility District. The customer population has grown by 35% since 1970 while overall water use has declined by 45%.

In recent years, residents have increasingly swapped out grassy lawns for drought-smart landscaping, and they are currently limited to watering outdoors no more than three days per week. These measures have reduced water use during the ongoing drought by 14 to 15% — what Pook describes as “conservation on top of conservation.”

Green grass will go brown next year, and in the long run, vast areas of lawn will probably disappear permanently as Californians adjust to aridification.

“I see communities prioritizing socially functional turf versus non-functional turf,” said Dan Drugan, a spokesperson for the Calleguas Municipal Water District, which supplies, among other towns, for Thousand Oaks and Simi Valley.

In October, the Metropolitan Water District passed a resolution encouraging communities “to reduce or eliminate irrigation of non-functional turf with potable water.” This followed a May, 2022 emergency order from the State Water Resources Control Board banning non-functional turf irrigation with potable water on commercial, institutional and industrial properties statewide. The Pacific Institute has calculated that such efforts could save California as much as 400,000 acre-feet of water annually.

But no matter how tight the state’s water supplies get, keeping urban trees alive will probably be a priority.

“We’re seeing, in all urban areas, a frantic effort to conserve urban forests,” Mount said, noting that urban trees provide shade, reduced ground-level temperatures and natural water treatment services.

Even in communities served by Las Virgenes, where much of the water under current restrictions is designated for health and human safety uses, spokesman McNutt expects residents will hand-irrigate with buckets of shower water and pots of kitchen water to keep trees alive.

“The last thing that anybody wants – anybody – is for the trees to die,” he said.

Mount, who recently eliminated most of his own backyard turf — sparing just a narrow strip for his dogs — said he takes some solace in the fact that green grass remains a prominent feature of institutional landscaping, for it means there is still room to improve.

“That makes me more sanguine than most about the future,” he said.