Like many voters across California this fall, those in Hayward and Fremont have been flooded with mailers targeting the two Democrats tussling for a seat in the state Legislature.

Fremont Mayor Lily Mei is slammed for her role in a secretive severance payout to the former city manager, who has been charged with embezzlement. Her opponent in the state Senate race, Aisha Wahab, a Hayward city councilmember, is accused of “elder abuse” for supporting a landlord who evicted older tenants.

One thing the mailers have in common: They are funded not by the candidates, but by outside interests.

Independent expenditure committees — political spending groups that are legally required to be unaffiliated with the candidates they’re trying to support — have spent nearly $40 million since Sept. 1 trying to influence competitive legislative races across California. With voting through Tuesday, that’s 25% more than what independent expenditure committees, or IEs, spent on Assembly and state Senate general election races in 2020, nearly twice as much as was spent in 2018, and just slightly below 2016.

While the IE spending is a relatively small share of all the political cash now sloshing around California, the mailers and ads financed by these committees — concentrated into just a handful of competitive races in the final weeks of the campaign — can play an outsized role in shaping key voters’ perceptions.

Because these committees are often given innocuous names that do not mention their funders, the average voter may not know who exactly is behind a particular ad. As a result, IEs often specialize in the dark arts of negative campaigning — withering and occasionally fact-bending critiques of targeted candidates. When the mudslinging is coming from an independent group, it’s less likely to tarnish the image of the favored politician, whose own campaign can focus on positive messaging.

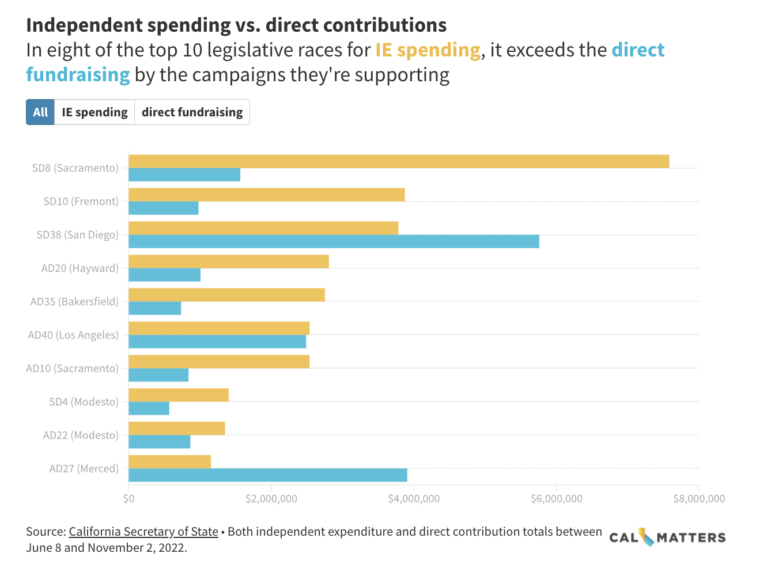

And unlike donations made directly to a candidate, spending by these IE committees is not subject to campaign contribution limits. That allows some of the state’s biggest economic interests to pour hundreds of thousands of dollars into a single legislative race, whereas contributions to campaign-run committees are capped at $4,900 per election. Often, IEs will spend more boosting a candidate than their own campaign.

In the 10 legislative races with the most IE money this year, spending has reached nearly $30 million since June. Contributions made directly to the 20 candidates in those races is less than $19 million. Most of these races pit one Democrat against another for a spot in the Legislature, where Democrats hold two-thirds super-majorities that enable them to pass tax increases and take other actions without any Republican votes.

This outside spending is a perennial feature of California elections, but this year the stakes may be especially high for industries, labor groups and others with an interest in the legislation that comes out of Sacramento.

Thanks to a wave of incumbents hitting their term limits or announcing early retirements earlier this year, California voters are being asked to fill 31 open seats in the Assembly and the Senate, of the 100 spots in the Legislature up for grabs on Tuesday. The first orders of business for this new class of legislators are likely to include picking the next Assembly speaker and voting on Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposal to tax the “windfall profits” of oil and gas producers.

“Every cycle we always say it’s an unprecedented level of spending,” said Doug Morrow, a former Democratic Assembly staffer who publishes a daily tracker of independent expenditure. “I think we are going to meet that without a doubt.”

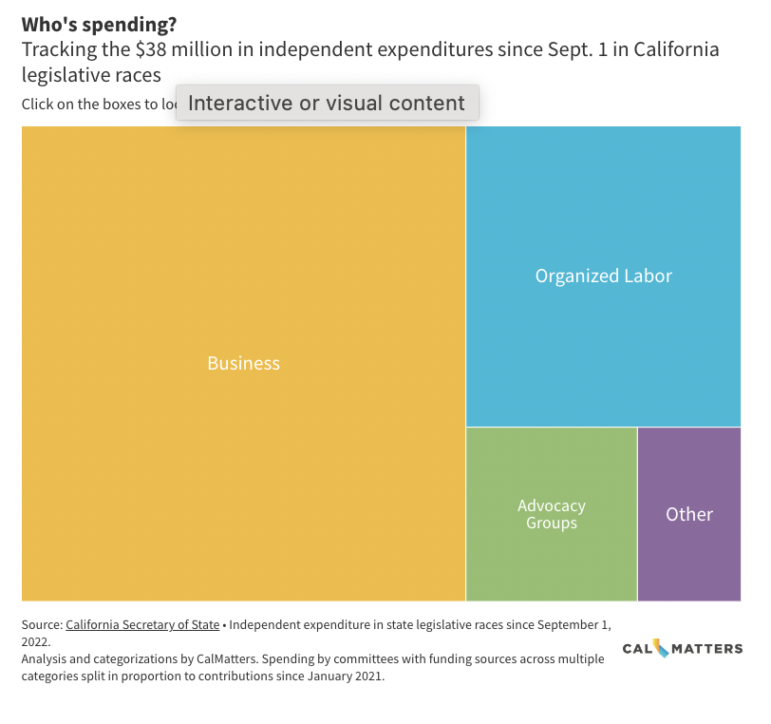

No surprise, the biggest sources of outside spending in legislative races so far are oil and gas companies and electric utilities. Together, those groups have spent more than $7.6 million, roughly one-fifth of the total. Most of that spending has been unleashed since Newsom announced his oil tax plan; the oil industry’s flagship IE committee dropped nearly $5 million into seven legislative races on Oct. 10 alone.

Other big spenders include:

- DaVita and Fresenius, the dialysis companies combating Proposition 29, a third union-backed proposition to regulate their clinics, and who have fended off similar attempts in the Legislature. Davita has spent $2.3 million directly, and since July the two companies together have contributed another $1.4 million to separate committees that have spent $5.4 million in state legislative races.

- The Service Employees International Union, one of the largest union umbrella groups in the state, has contributed $2.8 million to independent expenditure groups through its local chapters and its statewide council. The largest of those, Nurses and Educators California, which also received a small fraction of its funding from unionized school workers, has spent more than $1.5 million on legislative races.

- Realtors, both through the state association and individually, have channeled more than $2.6 million through nine IE committees.

- A committee supporting Robert Rivas’ bid to become the next Assembly speaker has sprinkled more than $550,000 into 15 open Assembly seats. That doesn’t put the PAC in the top 20 list of big independent spenders this year, but it is drawing a lot of attention. With all the committee’s funding from sitting lawmakers who might otherwise route those funds through the state Democratic Party, it’s seen by many as a direct financial provocation to Speaker Anthony Rendon.

A ‘barrage of attacks’

In the East Bay Senate race, Keep California Golden, one of several IEs opposing Wahab, has spent more than $700,000 so far in the race, with roughly a quarter going toward ads and polling to back Mei and the remaining 75% being spent attacking Wahab.

Other anti-Wahab spenders include Keeping Californians Working, funded by charter school advocates, the parent company of Southern California Edison and other business interests; Jobs PAC, sponsored by the California Chamber of Commerce; and Housing Providers for Responsible Solutions, a coalition of Realtors, landlords and developers.

Since Sept. 1, 17 committees have spent a total of $2.3 million to help Mei and $1.5 million to benefit Wahab. They do that by either boosting their preferred candidate or tearing down her opponent.

More often than not, they’ve opted for the latter.

One mailer paid for by Keep California Golden claims that Wahab endorsed Sajid Khan, who lost in the June primary for Santa Clara district attorney. Khan argued that criticizing the sexual assault sentence handed down to former Stanford University swimmer Brock Turner as too lenient would be harmful to communities of color.

While Wahab took part in campaign events sponsored by the local Democratic Party and the Working Families Party alongside Khan, she didn’t officially endorse him. Wahab says she’s disturbed that the mailers would use victims of sexual assault for political gain; her campaign has sent a cease-and-desist letter trying to stop the mailers.

“The people that even came up with these lies genuinely should be ashamed of themselves, and they should be fired and never work in politics again,” she told CalMatters.

“There should be some recourse for people dealing with IEs that literally can say whatever they want and then hide behind the First Amendment.”

Mei, who has been attacked in mailers from IEs backing Wahab, condemned the “barrage of attacks” in the race.

“Women should be allowed to run on their merits — not attacked based on gossip or guilt by association,” Mei said in a statement from her campaign. “Attacks like these devalue our lived experience as leaders committed to public service and making a difference in the community.”

Some local political watchers say the bevy of attack ads has set the terms of the debate.

“It’s unfortunate that the overall tone of the race has been so negative,” said Al Mendall, a former city council member from Hayward. “I wish the debate was focused more on issues and less on extraneous issues and negative attacks.”

Mei’s biggest supporters are charter school advocates and DaVita. Opportunity PAC, a committee funded by teachers’ unions, SEIU and other organized labor umbrella groups, has spent more than $663,000 opposing her.

For the entire campaign, independent expenditure committees have put in $3.8 million to either support Mei or oppose Wahab, far more than the $1.1 million Mei has raised for her own campaign. And IEs have invested $2.9 million to back Wahab or attack Mei, while Wahab has raised $1.2 million.

Strange political bedfellows

For the average voter, the path a dollar takes from a corporation’s treasury or union’s political fund to the attack ad mailer in their inbox can be hard to follow.

Keeping Californians Working, one of the groups boosting Mei, isn’t funded by a single source or industry group, but represents several different spenders. California law requires the committee to list its top three contributors from the prior 12 months who have donated more than $50,000. In the case of Keep Californians Working, that’s Farmers Group, a PAC funded by employees of the Farmers Insurance company, Uber and Edison International.

But that’s only the top three. To learn about the other major contributors — the state’s largest charter school advocacy organization, DaVita, trade groups for soda manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies, and the owner of SoCalGas and San Diego Gas & Electric — a voter would have to dig through the committee’s filings on the state’s rickety campaign finance data portal.

And finding out who funds the funders — the Charter Public Schools Political Action Committee, for instance, received more than 40% of its money this general election from Walmart heir Jim Walton — requires yet another layer of digging.

That lack of transparency has its benefits for funders, said Dan Schnur, a political analyst who teaches at USC and who used to lead the California Fair Political Practices Commission, the state’s campaign finance regulator.

“The average voter isn’t going to spend a great deal of time digging into the identity of these large-scale funders, and so an innocent sounding name of an independent committee is a very effective shield,” he said.

But if voters don’t know who funds the IEs, the candidates do. “The candidate is going to care a lot more about who funds these efforts than the average voter. So they’re going to know and they’re going to remember.”

A double-edged sword

From a candidate’s perspective, a flood of friendly spending from outside groups has its obvious benefits. But it can also come with its costs.

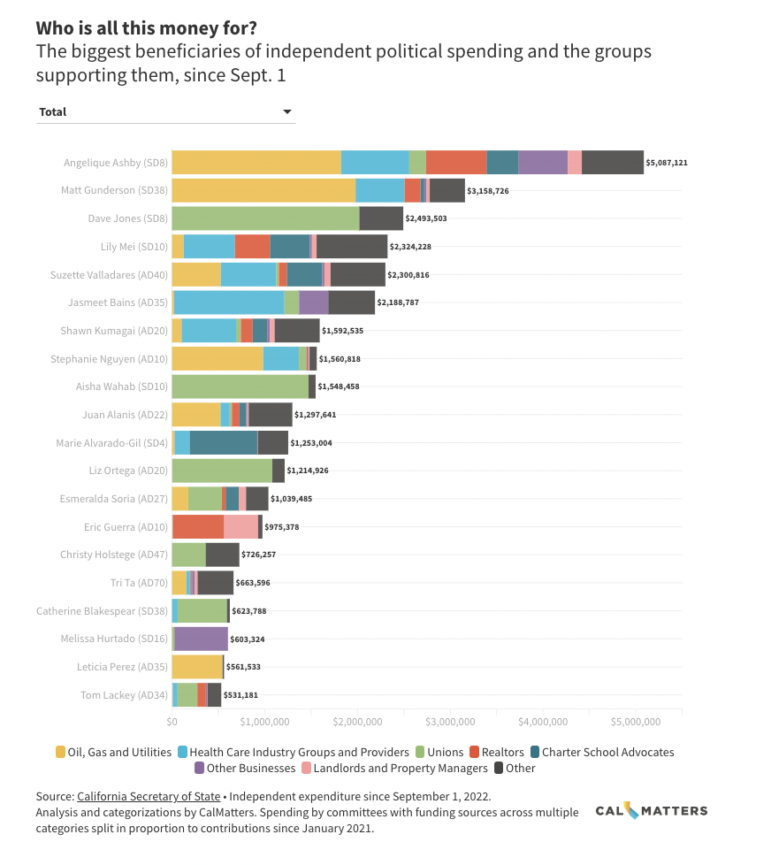

In the state’s most expensive legislative race, Democrat Angelique Ashby has been the beneficiary of nearly $2 million in spending by oil and gas companies and utilities. That includes spending by the oil and gas industry’s flagship independent expenditure committee, the Coalition To Restore California’s Middle Class, to support Ashby and oppose Dave Jones, her Democratic opponent for the state Senate seat representing Sacramento. But it also includes energy industry money routed through other committees.

That gusher of money has helped elevate Ashby while bashing Jones. But the IE spending has also opened Ashby up to the criticism — made regularly by Jones and his allies, including in multiple mailers funded by a labor-backed IE committee — that she is the candidate of “Big Oil.”

Ashby has denounced that support, while pledging to work with Newsom on his proposal to cap “windfall profits” and “out-of-control gas prices.” Jones supports the governor’s plan.

Also supporting Ashby, with more than $1.1 million in spending, is another IE — Fighting for Our Future Committee, funded by the Realtors, the California Building Industry Association and California Apartment Association — that has sent mailers calling Jones a career politician who wants to “take away Medicare” because of his support of single-payer health care while state insurance commissioner.

In the overlapping state Assembly race, Eric Guerra, a Sacramento City Council member, has been buoyed by nearly $1 million in outside spending by the committee funded by Realtors, landlords and developers. During his primary campaign, he also got some outside financial help from charter school advocates and a committee largely funded by the soda industry.

Guerra’s campaign distanced itself from that IE spending. “We may not have done things the way they’ve done them, but that’s really not our choice. What they put out is not our responsibility,” said Michael Terris, Guerra’s spokesperson.

But Terris did note that Guerra’s Democratic opponent, Stephanie Nguyen, an Elk Grove City Council member, is backed by the same oil industry committee that supports Ashby.

“When Big Oil has come in with over 1 million for Stephanie Nguyen, we wonder about that,” Terris said. Guerra has “been pounding at Big Oil on gas prices and has vowed to support the governor in efforts to rein in the price at the pump.”

Nguyen’s campaign told CalMatters she supports giving families relief from high gas prices, and wants to see more details from Newsom’s proposal.

For her part, Nguyen was hit by an IE mailer about a tax lien on her business, a nonprofit that helps Asian immigrants. Andrew Acosta, spokesperson for her campaign, said that attack caused a drop in donations. The nonprofit has sent a cease-and-desist letter on the mailer.

“That’s the real-word implications,” he said. “These ads that people think, ‘This is a nice hit on her,’ is wrong.”

Amar Shergill, chairperson of the California Democratic Party’s Progressive Caucus and a critic of what he sees as the party’s dependence on oil industry spending, said that candidates should have to either defend the financial company they keep, or forcefully renounce the money.

“Saying that ‘I don’t have control over independent expenditures’ isn’t enough,” he said. “They should be asked to explain what their policies show that would attract that kind of expenditure.”

A glut of outside spending can also make a candidate’s life more difficult even after Election Day. For someone who might be earnestly skeptical of Newsom’s proposal to tax oil companies, for example, a surge of oil industry support could call into question the sincerity of that future “no” vote.

Morrow, the independent expenditure tracker, recalls the possibly apocryphal quote from former Assembly Speaker Jesse Unruh about the relationship between lawmakers and special interests: “If you can’t eat their food, drink their booze…and then vote against them, you have no business” being in the Legislature.

In the December special session on the windfall tax, newly elected legislators “are going to be put to the test for that,” said Morrow. “I don’t think they asked for Chevron to come in and help push them over the line, but naturally, if they vote the wrong way, they’re going to get slammed.”