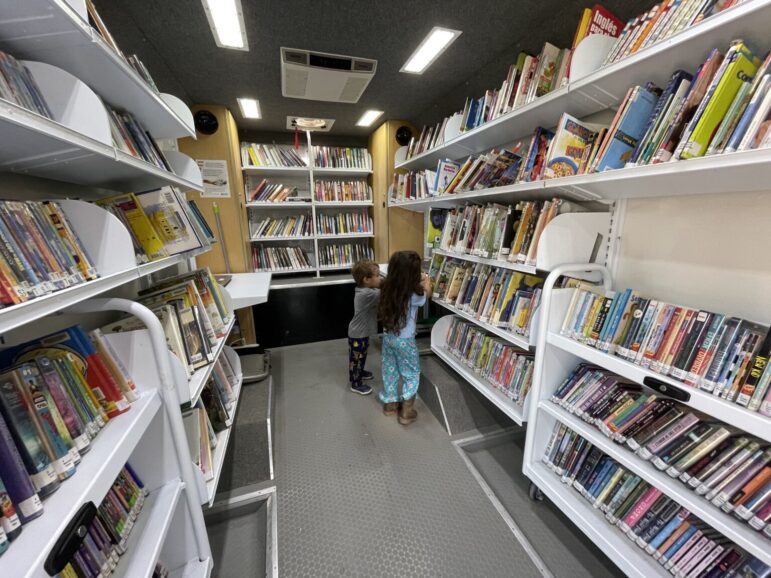

Visiting the library in the small town of Planada means visiting a bookmobile with no air conditioning in the sweltering heat of the San Joaquin Valley. But Sofia Rodriguez visits often, pulling her young children in their red wagon. The youngsters are bookworms who eagerly anticipate exchanging their library books for a stack of new ones.

It wasn’t long ago that the town of 4,100 had its own community library. But in 2014, weekly bookmobile stops replaced brick-and-mortar libraries in Planada and three other communities in Merced County. Citing budget woes, the County Board of Supervisors voted to shutter four library branches, leaving just 12 locations — half the number it once had.

“I think not having a library is something that causes a lot of the youth to be at home, locked up in their rooms,” said Olivia Gomez, a community liaison at Planada Elementary School District.

In recent years, crime and gangs have become serious problems for Planada, Gomez said. The town needs a library, a “second home” where the community can gather when they’re not at work or school.

Gomez has fond childhood memories of Planada Library. It wasn’t just a place to read, but a vibrant community center where she could hang out with friends, join a club and watch movies.

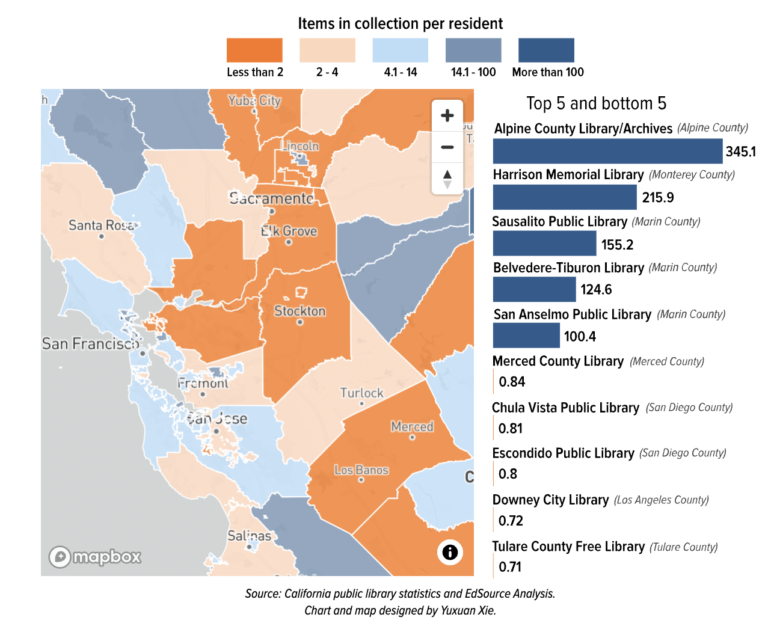

The shrinking footprint of the Merced County Library is a consequence of having one of the most poorly funded library systems in the state. Its libraries had $12 in income for each resident in 2020-21, according to the California State Library. By contrast, neighboring Santa Clara County Library, which serves much of Silicon Valley, boasts $147 in funding for every resident, among the highest in the state.

A library system’s annual income per resident is a key number that influences nearly every aspect of a library such as staffing levels, the quality of materials available to check out, whether professional librarians staff branches, the prevalence of fines and fees, how many hours the library is open or, as is the case in Planada, whether a community has a library at all.

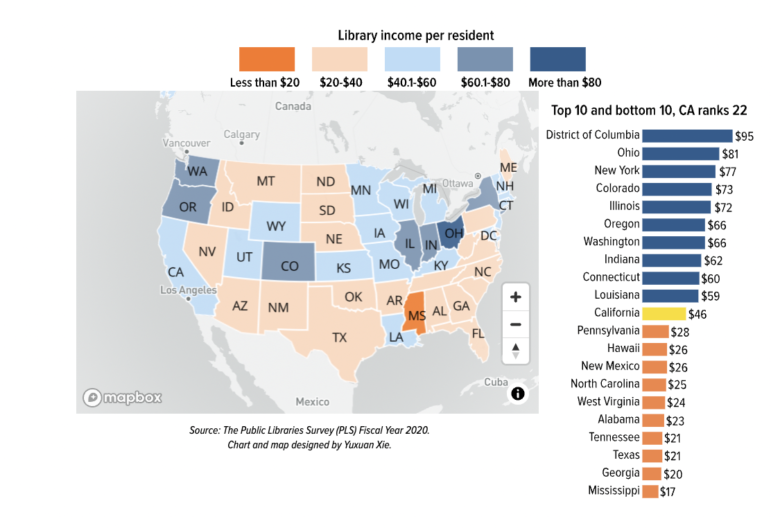

Vast disparities in California’s libraries mirror the state’s yawning equity gaps: The state’s most underfunded libraries are found in counties with high poverty and those with the lowest percentage of people over age 25 with a bachelor’s degree, according to census data. Libraries tend to be better funded in wealthier coastal and urban areas, and underfunded in the San Joaquin Valley, Northern California and other inland areas.

The question of how to fund libraries is made by elected public officials. Scant funding comes from the state or federal government annually — about 66 cents and 25 cents for every Californian, respectively. California’s library systems are hyperlocal agencies that receive 94% of their funding from local government.

John Chrastka, the founder of EveryLibrary, calls this the “ZIP code lottery.” EveryLibrary, a national political action committee focused on building voter support for libraries, has supported ballot initiatives aimed at raising funds for libraries in California and across the country.

“If you have a poor ZIP code, you have poor services; if you have a rich ZIP code, you have better off services,” he said.

Counties that fund libraries are also more likely to have an active Friends of the Library chapter that can raise funds and encourage volunteering, Chrastka said.

“There are times where the funding is limited because of economics, and there [are] times where it’s limited because of philosophy of government,” Chrastka said.

A tale of two library systems

The cities of Gilroy and Los Banos have a lot in common. They are close in size — Gilroy has 58,000 residents and Los Banos has 46,000 — and both are cities in agricultural regions with an increasing number of Bay Area expats seeking more affordable housing. Less than 50 miles separate the two communities, but the libraries seem to operate in different universes.

The Los Banos Branch Library is an older building just under 4,000 square feet with just one room for its patrons. It is open five days a week; no library in Merced County is open every day and most are open just two or three days a week.

By contrast, Gilroy has a gleaming, two-story library that spans 53,000 square feet — even larger than Merced’s main library. It features a meeting room that can hold 100 people and a classroom dedicated to adults learning to read. It’s open every day, like nearly every location in Santa Clara County, home to Silicon Valley.

The Santa Clara County Library recently hosted the Try-It Truck, a mobile engineering lab for kids. The library has also begun to invite park rangers into libraries to educate the community about local flora and fauna. Children who want to explore a local park can check out a backpack complete with binoculars, a magnifying glass, a first aid kit and books that help identify local wildlife.

The Santa Clara County Library is in one of the wealthiest counties in the state, but it makes efforts to address equity issues in its communities, said library spokeswoman Diane Roche.

“We’re fortunate,” Roche said. “We want to be able to provide the best services, the best resources, as much availability and accessibility as we can.”

Recently, the library system created a new position for a community outreach specialist — a reflection of the library’s priority to provide the public information about housing, food, health care and other resources. Erik Poicon will visit library sites in the neediest parts of Santa Clara County: Milpitas Library and the Ochoa Migrant Center in Gilroy, which is a bookmobile stop.

“This position builds on this existing relationship with the public and allows libraries to go further in connecting people in need with the government and nonprofit services that they require,” said Mike Wasserman, president of the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors and president of the library’s Joint Powers Authority Board, in a statement announcing the hire.

All these facilities and services are possible thanks to Santa Clara County Library’s long history of success at the ballot box. In 1994, voters approved a parcel tax that also created the joint powers authority that governs the library system. Voters also regularly approve additional funds to improve library facilities. Residents of Gilroy easily passed a bond measure authorizing the city to borrow $37 million for a new library in November 2008 — during the Great Recession when many library systems were making cuts.

Dion Bracco, a longtime Gilroy City Council member, said he didn’t fully understand the importance of libraries until he joined the board of the Santa Clara County Library to represent Gilroy. Now the self-proclaimed conservative said he can’t find fault in the way this government agency is run — and neither do his constituents.

“It’s very fiscally well-run,” he said. “All the libraries are top-notch libraries. We get awards constantly.”

In contrast, Merced County’s library system has been financially troubled for decades. In 1993, Merced County briefly shut down its library system. This came on the heels of voters narrowly defeating a half-cent sales tax measure that would have helped the county avoid a financial crisis.

Patrons and Friends of the Merced County Library helped to resuscitate the library system, but it has continued to struggle. The shutdown of four branches in 2014 resonates in the tight-knit town of Planada that is almost entirely Latino, where just 5% of adults have a bachelor’s degree and where many who work in agriculture live in migrant camps.

Before she moved to Planada, Rodriguez took her kids to weekly story time in Merced. It was a way for her daughter, now 4 years old, to socialize and begin learning to read. She rarely makes the 10-mile trip now given the time and gas it requires.

“We definitely miss story time,” Rodriguez said.

There are improvements in the works. A long-awaited new bookmobile with a functioning air conditioner and Wi-Fi is scheduled to come online soon. Library advocates lobbied the county to open during the evenings as a pilot. Part of the main branch of the second floor is under construction so that it can be transformed into a teen center.

But the Merced County Library could use the funding that comes with voter support, said Donald Barclay, current Friends of the Merced County Library president. Unfortunately, neither the peak of the pandemic, nor the current period of inflation and high gas prices have seemed the right time to seek a tax increase, he said.

In the meantime, the library and its advocates are working to remind residents of libraries’ importance — an uphill battle when the system is a shadow of its former self, Barclay said.

“It’s been almost 50 years of people in Merced County not knowing what it’s like to have a really well-funded library,” Barclay said.

The role of libraries

Surveys show that Americans are making good use of their libraries. But a misconception lingers that public libraries’ importance has diminished as technology overtakes the flow of information. Library advocates argue the rising importance of digital access and literacy has made libraries vital in a new way. To start, public libraries are a rare free place for those who lack reliable access to the internet.

Public libraries complement the formal education system, but libraries serve a unique role that schools don’t replicate. It’s one of the few remaining public institutions where people from all walks of life are welcome, whether to read, relax in air conditioning or gather with a club without paying a dime, said Barclay.

That was crucial when the Oak fire struck communities just outside Yosemite National Park in July, said Mariposa County Administrative Officer Dallin Kimble. The Mariposa County Library became a site where residents could get crucial information and charge their phones, and where children could make art and play games.

Proposition 13 hurts libraries

Proposition 13 slashed property taxes in 1978, which financially devastated funding for education and California’s libraries. Libraries supported by waning general county funds haven’t often fared well against fire or law enforcement departments, especially during a budget crunch.

“Boards are faced with the question: Do I send someone to help with a heart attack or do I staff a library?” Kimble said.

Local ballot initiatives have been a lifeline for libraries on the ropes in California. Citing budget constraints, Lassen County stopped funding its libraries in 1992. Two years later, voters in Susanville approved a special library district that reopened the library, though the outlying areas of Lassen County are, to this day, not served by a library. The Fresno County Public Library is the best-funded library in the San Joaquin Valley thanks to a one-eighth cent sales tax first passed in 1998.

But by requiring a two-thirds majority on special taxes, Proposition 13 also made it harder for communities to raise funds for their libraries. In 2016, a measure to raise a one-eighth cent sales tax for libraries in Kern County failed with 51.7% of the vote.

During that election, Kern County faced another major hurdle for library funding: political opposition to taxation. Local Republican leaders, who supported a failed attempt to privatize the library system, opposed the measure. Kern County’s 900,000 residents now have the worst-funded county library system in the state with just $7 per resident in annual income in 2020-21. EveryLibrary worked in support of the measure, and its failure still stings for Chrastka.

He said local political leadership at the time was “unwilling to fund a community institution that has a provable multiplier effect on quality of life, educational outcomes and literacy services, because of a philosophy of government that says tax is theft.”

When states fund libraries

The Athens County Library in Ohio serves a population in Appalachia with even higher rates of poverty than Merced County, but its libraries have better funding than most in California.

That allows nearly all of its libraries to open at least six days a week for its 62,000 residents. It has a bigger budget than Merced County with over twice the number of librarians and a bigger collection of books. Its libraries offer unique services, such as allowing students to check out a bike to ride to school. And unlike Merced, it has been growing. Three of its seven branches have been added since 1974.

This is all possible thanks to robust funding from the state of Ohio. The state kicks in 57% of its funding, bringing its annual income to $62 per resident.

Disparities exist in Ohio, too, especially between those communities that can supplement the state funding with local funding and those that can’t, said Michelle Francis, executive director of the Ohio Library Council. Maintaining infrastructure can be a particular struggle. But compared with California, funding for Ohio’s library systems is downright lavish.

Ohio has the best funded libraries in the country, on average, thanks to a dedicated Public Library Fund that provides 48% of income for its public libraries. Each library system is guaranteed a basement level of funding, and some are more reliant on state funding than others.

Francis takes pride in the fact that Ohio shows its appreciation for libraries by regularly topping other states with its number of visits.

Ohio bests California in other ways, too: It has nearly triple the proportion of librarians. In poorly funded library systems like Kern and Merced counties, staff members split their time between two branches open two or three days a week. Many will not often have a trained librarian on staff.

Formal training in library science makes it possible to address patrons’ complicated questions and to design high-quality programming at the branch level, said the director of the Kern County Library, Andie Sullivan.

This is one reason Merced County Library struggles to provide programming at all its branches, said deputy librarian Amy Boese. Merced’s nonprofessional staff who do receive their library science degree often go elsewhere.

“That’s a detriment to our communities,” said Boese.

State funding alone isn’t a silver bullet. Hawaii’s libraries, for example, are almost entirely state-supported but that amounts to $26 in income per resident, according to the 2020 survey Institute of Museum and Library Services.

For financial stability, libraries should ideally have funding from several sources. In states where there’s an over reliance on one source of funding — whether local or state — there are less robust services, said Chrastka.

Ohio residents have fought hard to preserve high levels of library funding.

“I have to honor the state of Ohio,” said Francis. “They said, ‘Libraries are important, we are behind them, we have a strong belief in them,’ so we were able to get support directly from the state.”