More than 100 students in Lodi Unified School District spent part of the summer running relays and braiding jump-ropes from plastic bags, all while learning more complex writing and reading skills in English.

This summer school program was designed to strengthen English language skills for elementary and middle school students who speak another language at home and have not yet mastered English. At the same time, it aimed to give the 16 teachers who participated the skills to support these students throughout the school year.

The program, titled “The Prolific Plastic Pollution Problem,” focused on the history of plastic and the effects of plastic pollution.

“It was kind of exciting because I got to learn something new,” said 12-year-old Nicolas Magaña. “I learned that plastic could end up in some places in the ocean and it could pollute the air or the environment, and it could be bad for us.”

Nicolas said the class helped him improve his writing, which he hopes will serve him in seventh grade.

Since 2015, the San Joaquin County Office of Education has been working with different school districts to offer courses like this one, designed by Karin Linn-Nieves, director of the county office’s language and literacy department. Linn-Nieves is a former teacher who has 36 years of experience working with English language learners. She said one reason she designed these courses is that most teachers do not have enough training on how to deepen students’ knowledge of English.

“It’s showing teachers how to take texts that are a little more difficult than they’re used to giving kids and how to make them accessible, and then really juice the language out of them,” said Linn-Nieves.

She bases the curriculum on California’s English language development standards, which are supposed to guide teachers on how to help students who speak a language other than English at home to build English proficiency.

“We have this beautiful set of ELD standards now that most teachers are unfamiliar with,” Linn-Nieves said. “So my personal charge has been making these standards more understandable through concrete classroom examples.”

Seventy percent of teachers nationwide said they didn’t feel fully prepared to meet the needs of English language learners, in a survey conducted by the English Learners Success Forum, a collaboration of researchers, teachers, district leaders, and funders.

Renae Skarin, senior director of content at the English Learners Success Forum, said California does more training than many other states, but teachers often still do not get enough practical training on how to use strategies in the classroom. Ideally, she said, teachers need to learn how to integrate language development with content so that students are learning both language and content at the same time. In addition, it is important for teachers to have time to work together to analyze student work and discuss how their strategies are working.

“That’s so powerful, even if you can do that once a week, or once a month, where you get teachers talking together, bringing in data and research and looking at student needs and where students need more support, and really intentionally target student needs in the moment,” Skarin said.

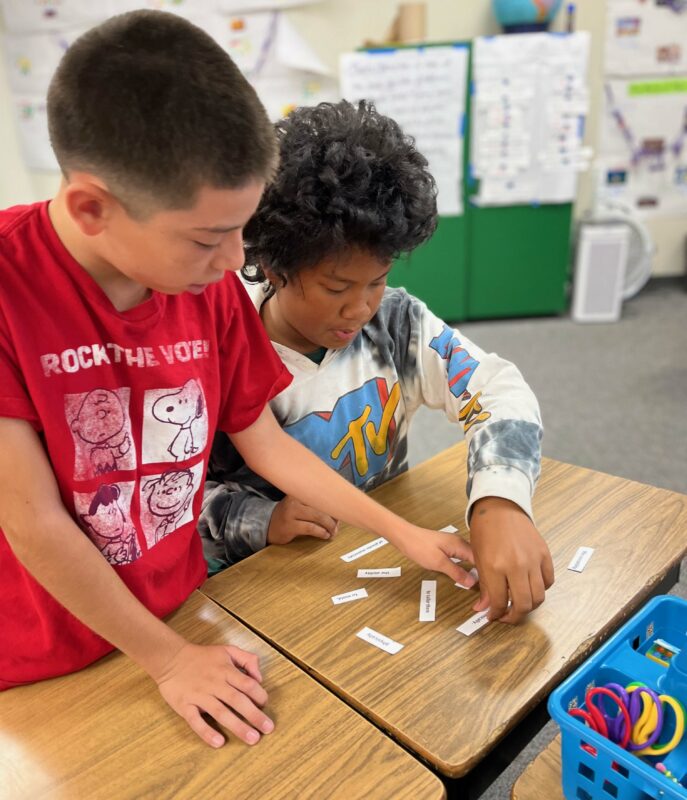

Linn-Nieves designs her courses to be interactive and hands-on so that students are excited about learning. In one activity called “running dictation,” students break up into teams. One student runs across the room, reads the first sentence in a paragraph, tries to remember it, and runs back to the team to tell them what the sentence is. If they can’t remember, they have to run back to read it again. Another student writes the sentence down, and two others help with spelling and remembering what the other student said.

“So the kids have read and re-read, they’ve written, they’ve listened, they’re using all the domains, but they think it’s a game,” said Linn-Nieves. “We’re practicing literacy on steroids.”

When they are done writing down the whole paragraph, they analyze the text, picking out different kinds of words, like which are verbs, prepositional phrases, pronouns, or text connectives — words that join together other words, such as and, also, furthermore or besides. These little words are often the ones that most trip up students for whom English is a second language, Linn-Nieves said, because they often don’t get explicit instruction and practice with them.

In another activity, called “vanishing text,” the teacher writes a sentence on the board, the students read it out loud a few times, and then the teacher erases a word and asks them to read it again, then erases another word, and so on.

“By the time you’ve erased six words, they have the sentence memorized,” Linn-Nieves said.

Lodi Unified teachers said they learned a lot by participating in the program.

“Sometimes we set the bar too low. We think, ‘Oh, gosh, they really don’t speak clear English,’ instead of realizing they can do it. Yeah, they’re going to need more scaffolding, they’re going to need more modeling, more hands on, more repetition with it, but it’s still something that they can achieve,” said Colleen Guidi, a reading intervention teacher who taught fourth graders this summer.

Two teachers co-taught each class and had preparation time built into every day. Students were only present in the morning, and teachers spent the afternoons discussing how different strategies worked, getting training on how to improve their teaching, and analyzing student work. For example, if a student was writing very basic sentences, the teachers discussed how they could get them to write more complex sentences.

“I really appreciated the ongoing professional development and the constant look at student samples,” Guidi said. “It really made faster shifts in our teaching.”

It is unusual for teachers to have time every day to analyze students’ work, discuss how different strategies worked or not, and make changes based on those observations, said Jeff Zwiers, a senior researcher at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and the director of professional development for the Understanding Language initiative, which is focused on improving instruction for English learners.

“I like the fact that they can probably try out something one day, and if it doesn’t work great, they talk about in the afternoon and change it,” Zwiers said. “There’s immediate feedback and reflection.”

Ideally, Zwiers said, teachers would be able to continue this kind of work during the year and share the strategies with other teachers in their district.

“The challenge of it, of course, is time,” Zwiers said. “You can do it in summer school, but I don’t see it happening very often at 3:30 every day for teachers during the year.”

The course in Lodi Unified was designed for teachers to gradually prepare more of the curriculum themselves. The first week, teachers were given all the activities and materials. The second week, teachers were given activities but had to prepare their own materials. The third week, they began coming up with their own activities.

For Marina Berry, who taught sixth through eighth graders in the summer school program, improving teaching for English learners is personal. She grew up in Lodi speaking Spanish at home. Her parents were migrant workers and spent six months of the year in Mexico and six months in California when she was in early elementary school. Berry said she missed some lessons because of going back and forth between the countries and never fully learned nouns, verbs and adjectives, for example.

“I always struggled with writing growing up,” said Berry. “I learned how to write in high school and college. But I didn’t understand what a noun was, what a verb was, until I actually explicitly taught it in first grade. I was like, ‘Oh my lord, if they only took the time.’”

Berry said she will use some of the activities she learned this summer in her own first grade classroom this year. For example, she plans to have students create sentences with a noun, a verb or prepositional phrase and an adjective. For example, the students might come up with a sentence like “The amazing, beautiful scientist walks down the path,” and then sing it to the tune of “The Farmer in the Dell.”

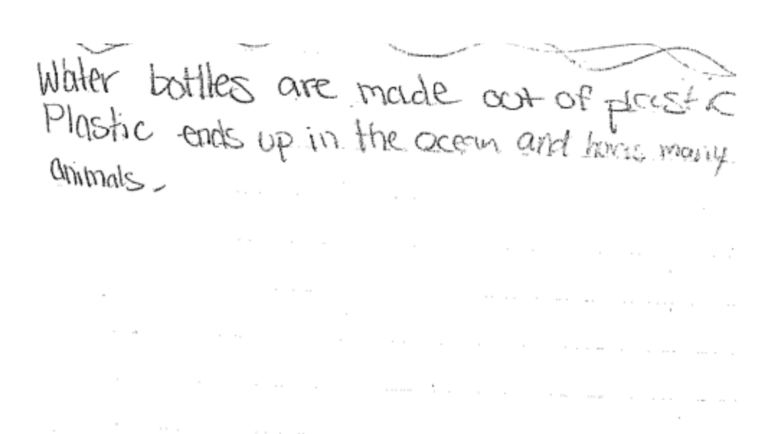

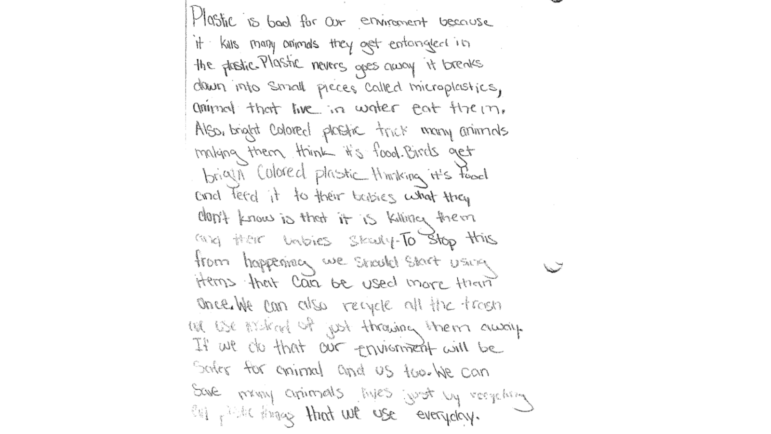

Berry and Guidi both said they were impressed by how much their students’ English skills improved over the course of three weeks. They said students began the summer writing only one or two short, simple sentences about what they knew about plastic. By the end of the summer course, they were writing long, complex paragraphs, using new vocabulary like “biodegradable,” “microorganisms” and “polymers.”

“I saw their articulation improve. I had a little girl that was nonverbal, she didn’t want to talk to anyone. By the end she was talking to us, she was talking to her peers. It was neat to see,” said Berry.

This year’s summer school course was Linn-Nieves’ last — she is retiring. But she hopes that the San Joaquin County Office of Education will continue her work, with more summer school classes for English learners — and their teachers — in the future.