Antonio Dominguez had never seen a car wash before moving to Los Angeles from Mexico in 1997. As a 24-year-old day laborer, he’d walk home each day, stop along a palm-lined boulevard and watch a team of mostly Mexican workers sponge, rinse, dry and polish a line of cars.

He was charmed by the waiting customers who seemed pleased with how their vehicles were left gleaming. And he simply loved the cars. In his Mexican hometown, there were few paved roads and cars were luxuries. “I just wanted to touch those cars, those new cars,” Dominguez said. “They came out so pretty.”

Dominguez worked five years at his first car wash job, earning only cash tips, and then was put on the payroll, though his weekly check often didn’t pay him for all of his hours, he said.

In his next job, at the Playa Vista Car Wash in Culver City, sometimes Dominguez and the other workers were told to wait in an alley for hours, uncompensated, or they were sent home with no pay, he and the state of California have said.

In 2019 the state Labor Commissioner’s office found Playa Vista had short-changed Dominguez and 63 other workers in wages. It said it was fining the company more than $2.3 million in wage theft violations and penalties, its largest fine ever issued against a car wash business.

Three years later those workers have not been paid. Playa Vista appealed the fine. Last week the Labor Commissioner said both sides had reached a settlement agreement in principle, without describing the details.

Playa Vista’s owner, Hooman Nissani, in his appeal of the fines and citations, has said the investigation was flawed and that an audit his company paid for indicates the car wash overpaid some of the staff. Through an attorney, he declined to comment to CalMatters.

Despite years of legislative efforts, some of America’s toughest labor laws, and some of the nation’s highest levels of income inequality, California’s enforcement of wage theft laws remains an exercise in frustration for workers and businesses alike, many experts and advocates said.

In California’s wage theft cases, workers can wait months or years to be repaid lost or stolen wages – even when state regulators step in.

Last year California workers filed nearly 19,000 individual stolen wage claims totalling more than $338 million, according to a database provided to CalMatters by the Labor Commissioner’s office.

While many claims did settle, the average case filed last year that did get to a decision was 334 days old — well over the 135-day limit set by law — and thousands of cases filed in 2021 remain pending.

“While the timeline for investigations can be lengthy, improvements in our laws have given the Labor Commissioner’s Office … new tools to assist workers in recovering stolen wages,” said Erika Monterroza, a spokesperson, adding the state has made progress at hiring people to help enforce those laws.

She did not comment on the Playa Vista car wash case. The Playa Vista action was brought not by individual workers but by a state enforcement office, yet it is involved, years later, in a quasi-judicial and a civil litigation process, according to state documents.

It is one of many investigations aimed at targeting wage theft in specific industries.

Wage theft — or the failure by employers to pay employees what they are owed — typically impacts the most vulnerable: people with the least education and financial means and fewest legal protections. Often they are immigrants.

Dominguez said he believes he was taken advantage of because he was ignorant of his rights.

“I would tell myself that in this country I was nobody,” he said.

Now at age 48, Dominguez has graying black hair, bags under his eyes, deep wrinkles and a weary smile. He has described his experiences working at car washes to state investigators, in testimony, and in interviews with CalMatters.

He grew up the son of a small-plot farmer in the Mexican village of Molcaxac, which he said means “bird’s nest” in Náhuatl, the Aztec language. Situated in the central state of Puebla, Dominguez remembers the countryside as a semi-desert marvel of jaguars, eagles, coyotes, cacti, oak trees and cascading waterfalls. His childhood home was a sheet metal house and his father wore huaraches (leather sandals) instead of shoes. They could only get by and never get ahead.

“We had nothing,” Dominguez said. “We were poor by nature. There was only enough to eat, and just the essentials.”

Dominguez migrated to Los Angeles, finding himself in Mar Vista, a neighborhood of midcentury homes and cramped apartment complexes east of Venice Beach. With few connections, Dominguez first found work as a day laborer. On his walk home each day, he passed a large full-service car wash. He got a job there, he said, after striking up a conversation with a car wash worker who coincidentally was from his village.

Dominguez said he worked at that car wash from about 1997 to 2005. For the first five years, he said, he made tips only, often little more than $15 a day, and his final years he was paid with weekly checks that barely were enough to cover his expenses and send some money home to his family in Mexico, chiefly his mother and sister.

Dominguez advanced in his car washing skills, learning all aspects of the business, he said. But in 2005 he returned to Mexico after longing for home and feeling disillusioned.

“You arrive at that moment where you say, ‘What am I doing here?’ ” Dominguez said. “Why suffer here if you’re better off over there?”

Around the same time that Dominguez began working in the car wash industry, Victor Narro, now a law professor and project director at the UCLA Labor Center, began researching low-wage workers as an advocate for the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, a Los Angeles nonprofit.

In 2002 Narro helped UCLA law students interview 23 car wash workers for one of the earliest research papers on the industry in Los Angeles. Interviewers found several of the younger, more recently hired car washers were being paid only in tips, and many expressed the attitude of gratitude for the work — calling themselves propineros, a play on the Spanish word for “tip.” Narro presented the paper to Sacramento lawmakers as evidence the industry needed regulation.

“I was shocked when I was encountering that,” Narro told CalMatters. “It was a major practice, and we knew it was a crisis.”

Workers also were being paid per car, or daily rates, and some were being asked to work off the clock, Narro said. He found an ally in civil rights and antiwar activist Tom Hayden, a state senator who in 1999 authored a bill that would have required car wash businesses to register with the Labor Commissioner and post surety bonds that could be used to recover unpaid wages and benefits.

Democratic Gov. Gray Davis initially vetoed the bill in 2000 but signed an even more robust version three years later, which along with the registration requirement, created a restitution fund for car wash workers. The law required employers to carry surety bonds of at least $15,000.

In 2008 the United Steelworkers and the AFL-CIO launched a mostly unsuccessful attempt to organize Southern California car wash workers. Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown in 2013 signed a bill that increased the bond car washes are required to carry to $150,000, but it exempted owners who signed bargaining agreements with unions. These days there are 28 Los Angeles car washes with United Steelworkers Local 675 members, two others in Orange County and one in San Diego.

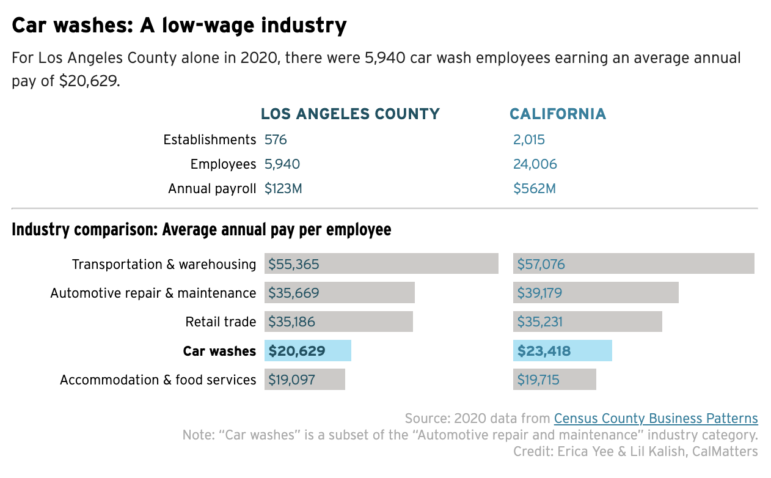

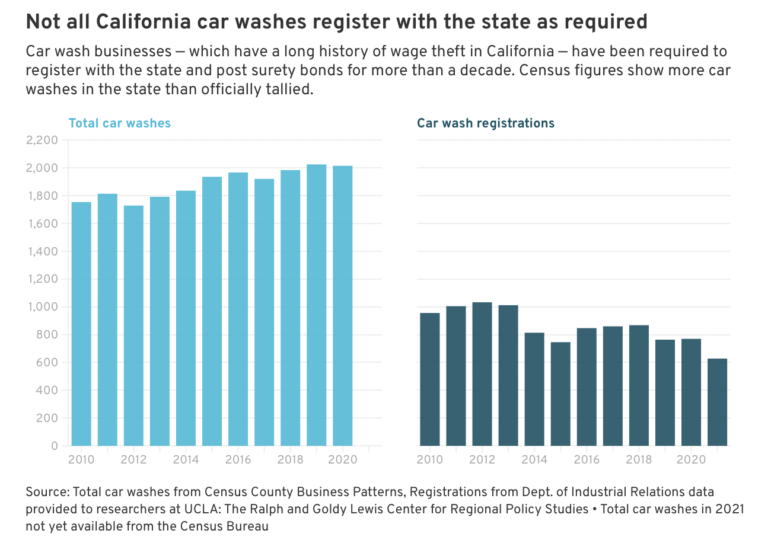

Critics say California’s enforcement of its requirement that car washes register with the state has lacked enforcement, particularly during the pandemic. A report this year by UCLA graduate students found 770 car washes registered with the state in 2020. But there were 2,015 of these establishments operating in California according to 2020 U.S. Census figures. Los Angeles County alone had 576 car washes.

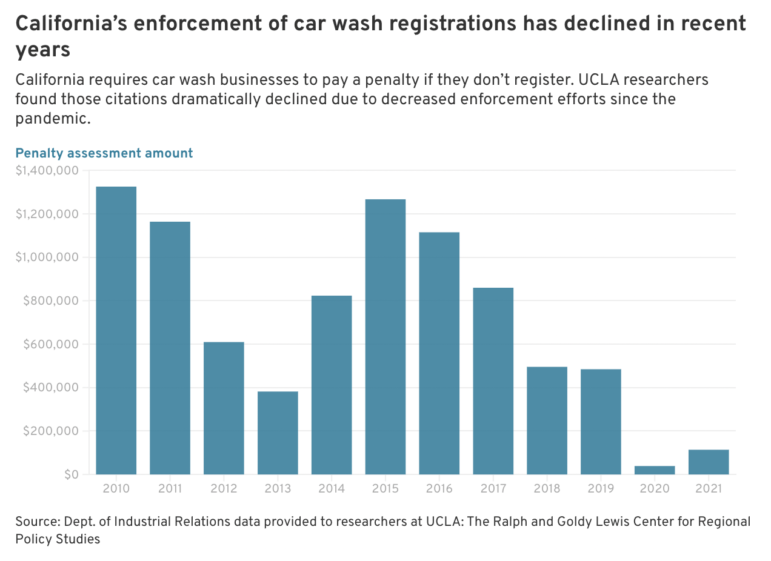

In 2020, the Labor Commissioner issued only five citations in 2020 to car washes for not registering and 13 in 2021. The agency had averaged 108 citations in the 10 years prior to the pandemic.

Assemblymember Ash Kalra, the San Jose Democrat who chairs his house’s Committee on Labor and Employment, said the Legislature needs to commit more funds to enforcement and the Labor Commissioner needs to deploy them.

“We need more resources and more accountability, particularly in industries like the car wash industry,” he said. “We need to raise our voices and make it very clear that we are collectively failing our workers throughout the state in industries where they need us the most.”

The state has added 288 people to the Labor Commissioner’s Office since January 2021, Monterroza said, including 116 in the Wage Claim Adjudication Unit and 63 in the Bureau of Field Enforcement.

The Labor Commissioner also gained new authority last year to put liens on the property of businesses that are the subject of the state’s Bureau of Field Enforcement actions, she said, to secure final payments for things such as wage theft. Recently, the commission office used this tool to collect $282,00 from another car wash business, she said.

David Murillo, executive director of the Western Carwash Association, said California’s enforcement of its car wash regulations puts those who comply at a competitive disadvantage.

“The good actors are paying for the bad actors,” added Chris Buscaglia, a former board member of the association. “We get the bad rap; we pay all the money. It’s a thorn in our side.”

By 2009 Dominguez said he had returned to Los Angeles and was working a new job at Playa Vista, a full-service car wash with a gas station and convenience store on the corner of Centinela Avenue. With his years of experience, Dominguez said, he started at $10.25 an hour, which was $2.25 above the minimum wage then. He was content and proud, he said, to send money home to support his family in Mexico. He was later promoted to detailer and got a dollar-an-hour raise, he said.

“Everything was going so well,” he said.

In 2014, Nissani took over the business, and the pay and work environment changed, said Dominguez, as did other former Playa Vista workers interviewed by CalMatters.

The workers described not getting paid for all their work, having to wait long hours off the clock and not being paid overtime, according to a state press release in 2019 describing citations the state issued against Playa Vista.

Nissani appealed the state’s citations, saying some of the workers’ statements are untrue. Since then, COVID-19 and the administrative hearing process have dragged the case on for three years.

In July 2020, the Labor Commissioner also filed a lawsuit against the car wash, Nissani and general manager Keyvan Shamshoni in an attempt to compel them to pay the fines and back wages. Shamshoni also was named in the original citation.

Nissani filed objections to the suit, claiming the workers’ statements to the state inspector were hearsay and not backed by evidence.

A trial in that civil case was postponed. During his appeal before the Labor Commissioner, Nissani has argued the investigation into his car wash was flawed, and relied on anecdotal evidence. His appeal brief said the state’s investigator coaxed workers to sign “untruthful statements” and that the state’s fines and wage assumptions are “grossly inflated” and “riddled with erroneous, unfounded assumptions.”

In August 2021 Playa Vista submitted evidence supporting its case, including its own audit by a Los Angeles consulting firm that concluded the carwash may have overpaid its workers.

Two former Playa Vista workers interviewed by CalMatters, Cesar Jacobo and Luis Diaz, told a different story. They also have described the changes under Nissani in sworn statements in the Labor Commissioner’s court case.

In his statement, 47-year-old Jacobo said the following:

Nissani called a worker meeting in November 2014. With one of the managers translating, Nissani introduced himself as the new owner and announced there would no longer be overtime pay. Nissani then asked workers to sign letters agreeing to no further overtime.

A few months later, Shamshoni told the staff they needed to report to work at 7:30 a.m. but workers would begin their shifts whenever managers decided.

“He said that we could not walk or wait around the car wash, as that would disturb the clients that were waiting if they saw us and wanted us to work on their cars,” he continued in his statement.

The workers waited in alleys near the carwash, resulting in unpredictable work hours. When Jacobo complained, he said, he was given fewer hours in retaliation. Lunch also grew to be a problem, with workers asked to wait long stretches, sometimes two hours uncompensated, before returning to work.

In early 2018, Jacobo said that he was promoted to manager but asked to be demoted — in part because he felt uncomfortable choosing which workers would get work and which would not.

In his statement, Diaz, 56, said he was a manager who had worked at Playa Vista for 18 years when Nissani took over.

In their statements, both Diaz and Jacobo said the new managers refused to call in additional workers even when the car wash was backed up with clients, in an effort to cut costs. Business deteriorated and workers went past eight hours a day as a result, they said.

“Under Hooman (Nissani), the car wash was almost always understaffed: The managers hired way fewer people to operate the car wash on a daily basis than the previous owners, but we still had the same number of cars to service,” Jacobo said. “Oftentimes, I was the only person working in the detailing section, or in other sections of the business, and leaving those sections to take a break would result in leaving a part of the business unattended.”

Playa Vista’s attorneys in their appeal wrote that the car wash was undergoing renovations, getting new car washing equipment, “as a result, the need for manual labor by employees diminished.”

Dominguez said he remembers no punch clock, no means provided to record his hours. Managers kept track of workers’ hours, he said, a point also made by Jacobo and Diaz in their sworn statements. Like Dominguez, they said workers were given no process to keep track of their hours.

More than anything, those long waits in the alley stand out in Dominguez’ memory. At times they would begin work at 8 a.m., other times 10 a.m., other times later, he said. As they waited their turn to work, the workers chatted, rested, played various games, even an occasional match of pickup soccer, Dominguez said. But mostly, they sat in frustration, he said, because they weren’t earning money.

Losing income when his family in Mexico depended on him plunged Dominguez into despair, he said. He worked other jobs on his days off, at times returning to day labor.

“If you lose a day, you have to make it up some other way,” Dominguez said. “There isn’t an option of being without work.”

In December 2017, Alejandra Hernandez, an inspector with the Labor Commissioner’s Bureau of Field Enforcement, received a tip about the pay practices at the Playa Vista Car Wash, according to court filings and records in Nissani’s appeal. By then, with 18 years’ experience, Hernandez had worked on at least 600 audits, 200 workplace inspections and 100 citations. The Playa Vista referral came from the CLEAN Carwash Worker Center, a non-profit organization born out of the 2008 unionization efforts. Jacobo is now an employee of CLEAN and Dominguez has done occasional outreach and education work for the nonprofit.

The referral was one of many stemming from the state’s enforcement efforts to eliminate wage theft in certain low-wage industries, including car wash businesses.

After years of individual workers struggling to navigate California’s lengthy wage claim process — often unsuccessfully — then-California Labor Secretary Julie Su began partnering with workers’ rights organizations in California to bring targeted, high-profile actions.

“The theory of this partnership is that your average worker who works in janitorial or in a restaurant or even in agriculture, they’re not just going to go on their own to report the labor law violation,” said Amaya Jennifer Lin, a campaign manager for the National Employment Law Project who has worked with 17 worker centers and the Labor Commissioner’s office over the last six years.

“We hope to create, ideally, ripple effects across not just a worksite but across multiple employers and across industries,” Lin said.

Business groups argue that the thousands of claims filed by workers last year are only a tiny fraction of California’s $3.5 trillion economy and that most businesses are trying to comply with labor laws.

“The vast majority … of California employers are compliant in paying wages timely and fairly while trying to untangle and decipher California’s complex and ever-growing body of employment law,” said Denise Davis, spokesperson for the California Chamber of Commerce.

Economists who study the issue argue that such claims data don’t fully capture how much wage theft exists in the economy because so many workers simply don’t report these violations.

When CLEAN’s referral about Playa Vista came to Hernandez, the inspector began an investigation that included surveillance of Playa Vista, two on-site inspections — including an “inspection warrant” on March 9, 2018 — and 19 worker interviews, she said in court records. Jacobo was one of the workers interviewed, Hernandez said in a sworn statement. Dominguez also spoke to investigators, according to records obtained through a public records request from the Labor Commissioner’s office.

Employees gave sworn depositions, including Shamshoni, and the Labor Commissioner’s office issued subpoenas for payroll records and other business documents after Nissani refused to cooperate, according to filings in the court case. A central part of Nissani’s defense has been challenging Hernandez’s audit, arguing she did not interview all of the workers and therefore the state’s citations were too high.

After the audit was complete in March 2019, the state issued 12 citations against Nissani, Shamshoni, and the business entity totaling $2.36 million.

The state noted “workers were required to report to an alley next to the car wash 30 minutes before the business opened to be selected to work that day. Those not selected were typically sent home several hours later without being paid for the waiting time. Workers were also frequently required to take extended lunch breaks with no split shift premium, or worked up to 10 hours a day with no overtime pay. Managers regularly altered workers’ time cards to reduce total hours worked,” in a press release about its findings and citations.

Dominguez said the process has been frustrating, like the days he worked at the car wash and waited in the alley. For the case, he would show up some days at a state office to testify remotely on one of their computers, only to wait around and eventually be sent home, he said.

While he awaits resolution of the case, Dominguez and four other car wash workers have launched a new venture. On a recent weekday in July Dominguez awoke at 6 a.m., he said, left his Mar Vista apartment and drove east to Montebello, traversing much of the city before traffic set in. He parked near a garage where he and a team of other self-employed workers, some from the Playa Vista case, keep a van stocked with car-washing equipment.

Dominguez, Diaz and some other car wash veterans started CleanWash Mobile, a worker-owned alternative to the car washes they’ve spent their lives in.

Before 7:30 a.m. Dominguez had pulled the CleanWash Mobile van up to the cracked, uneven driveway of CLEAN’s Los Angeles headquarters, a no-frills storefront with barred windows and a Farmers Insurance office as their back neighbor.

The cooperative had 10 customers lined up for a range of car washing services, including some detailing work. By 8:30 a.m. Diaz and Rodrigo Hernandez, another former Playa Vista worker, had arrived, donning broad brimmed hats to protect from the rising sun and light beige polo shirts over their work clothes.

Their prices range from $40 for a sedan express wash to a full detail for $300. Adonia Lugo, a bicycle activist, university lecturer and recent appointee to the California Transportation Commission, got her car washed that day, saying she wanted to support the movement.

“This is worker-owned and these are people who are fighting to improve working conditions,” she said. “That’s totally a sustainable transportation issue.”

The pandemic ended Dominguez’ time at Playa Vista, he said, and like many low-income workers, he struggled during lockdowns. He and his sisters sold food out of their kitchen to make ends meet.

“The bills don’t stop,” Dominguez said. “We all helped each other out, and that was the only way we survived.”

Dominguez counts himself lucky. One of his coworkers, Eduardo Flores, who also was a party to the Playa Vista case, died of COVID.

Dominguez has suffered his own losses. His sister died in July. His mother died a year ago.

“I lost my mom, I lost my sister, and they depended a lot on me, so now only I depend on myself,” Dominguez said. “My future is in my own hands.”

As more customers pulled their cars up, Hernandez, Díaz and Dominguez took turns lathering and scrubbing exteriors with sponges and neon colored towels. The men’s movements were measured, their gaits slow. After a few hours all of the men’s cheeks were red and sweaty.

He would work until 7 p.m., not unlike the hours he put in at a commercial car wash, but the pressure was different, Dominguez said, taking a break, watching cars zoom by on Washington Boulevard. Working for yourself, he said, you can set the pace, take your time, cast your thoughts back toward home, toward a little village to which you might one day return.

For the work they do now, the men pay themselves $17.25 an hour.

CalMatters reporter Jeanne Kuang and data reporter Erica Yee contributed reporting.