Hundreds waiting hours for a monkeypox vaccine only to be turned away. Residents taking to social media to detail struggles getting diagnosed and treated. State and local leaders demanding federal action. Emergency orders declared.

At face value, these details paint the picture of a country and state in crisis, struggling to apply lessons learned from the past two and a half years of COVID-19 response. However, scientists, public health leaders, and physicians who spoke with CalMatters said infrastructure and resources augmented during the COVID-19 pandemic have, in fact, aided the monkeypox response.

Still, it has its faults.

“What we learned from COVID is that speed is everything. When we look at the response of monkeypox later on, we’ll see speed is the main thing we take issue with,” said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, infectious disease specialist at UC San Francisco and member of the state’s scientific advisory committee for monkeypox.

California has the second-highest number of monkeypox cases in the country, with more than 1,300 infected residents, according to the latest state data. Gay and bisexual men have been disproportionately impacted, making up 96% of cases.

Some experts say we’re already past the point of controlling monkeypox, which was first reported in California in late May.

The culprit? Too little testing and treatment and too few vaccinations — all of it layered with too much red tape at both the federal and state level. It’s a familiar refrain and one that has frustrated state and local leaders.

A cadre of California lawmakers asked the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to allow the state to reallocate some of the $1.5 billion in COVID-19 response funds to monkeypox. Others submitted a $38.5 million emergency state budget request for monkeypox resources, and the California Department of Public Health sent a letter to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention requesting 600,000 to 800,000 vaccines — that’s more than half of the total available doses for the entire country.

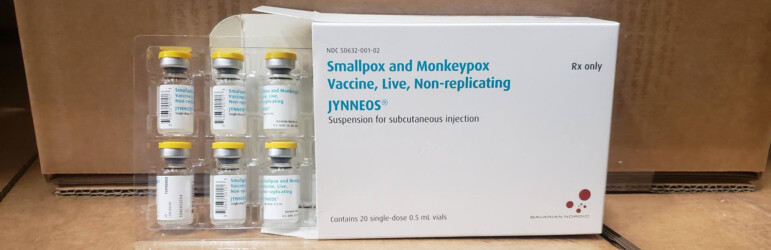

California is expected to receive 72,000 doses of the JYNNEOS vaccine used for monkeypox, with an additional 43,000 sent straight to Los Angeles County. Those doses represent “a drop in the bucket” of what’s needed, state epidemiologist Dr. Erica Pan told county health officers in a meeting last week.

During a Senate oversight hearing held Tuesday, Sen. Scott Wiener, a San Francisco Democrat, said “severe public health failures” at the federal level led to the current outbreak.

“We need to turn this around,” Wiener said. “We need to continue to push hard to make sure that our state, federal, state and local public health authorities are directing the resources where they’re needed most and rapidly expanding support for vaccination, testing and treatment to slow and hopefully stop this spread.”

Despite continued resource challenges, public health systems are better prepared to respond to monkeypox than they were to COVID-19. In the early days of the pandemic, hospitals didn’t even have a way to quickly report how many COVID-19 patients were hospitalized or in intensive care.

“(Monkeypox) is a serious concern, but public health is far more prepared now than we have ever been,” said Sarah Bosse, Madera County public health director.

Madera County has not reported any monkeypox cases, but neighboring Fresno County has seven cases. Bosse said her department is already in talks with the state on how to redirect COVID-19 contact tracers to monkeypox response and how to scale up vaccination clinics.

“The state has been very proactive in identifying counties that need additional support,” Bosse said.

In comparison, in 2020, 11 counties declared local emergencies for COVID-19 before Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a statewide emergency, freeing up staff and fiscal resources. This time, only San Francisco beat the state to the punch, a signal that state officials are closely in tune with local needs.

“To someone like me who has been doing this for 30 years, this actually moved very fast,” said Dr. Timothy Brewer, an infectious disease specialist at UC Los Angeles, who recalled it was three years between when the first case of AIDS was described in Los Angeles and identification of the HIV virus. It took an additional three years before the first treatment was developed.

Comparing monkeypox to the HIV/AIDS epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic — both of which activists and state leaders have done — isn’t exactly apples-to-apples. What researchers knew about each disease at the onset of their respective outbreaks and available treatments varied widely.

“What’s frustrating is that unlike COVID, which was a brand new virus that we had never seen before…with monkeypox we do know about it. It’s been around almost 70 years,” Wiener said. “We actually have a vaccine and an effective treatment. You would think that would be a recipe for very quickly controlling an outbreak.”

However, the influx of attention and money on the state’s chronically underfunded public health resources during the past two years has helped agencies ramp up for monkeypox much more quickly than they did with COVID-19.

For example, six months after the first confirmed COVID-19 case in California, the state was still rationing test kits and struggling to process a backlog of results. In comparison, one month after the first monkeypox case in the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention onboarded five commercial laboratories, making monkeypox testing widely available at hospitals and doctors’ offices. In the same time period, the California Department of Public Health doubled its weekly testing capacity from 1,000 to 2,000 tests with an average turnaround time of three days, far shorter than the 12 days reported for early COVID-19 tests.

The state also had to build data reporting systems for contact tracing, testing and vaccinations from scratch in 2020. County health officials say they’re now using those same systems for monkeypox. By Aug. 15, the state plans to launch a monkeypox vaccine appointment portal through the MyTurn website developed for COVID-19.

“We have weekly calls with (the state health department) and everyone is saying we need funding resources for this,” said Tulare County Public Health Director Karen Elliott. “I think that’s one of the reasons (the state health department) wanted the state of emergency. It cuts a lot of red tape.”

Some of that red tape stems from reallocating money earmarked for COVID-19 to monkeypox, which requires both federal and state approval. Public health funding is notoriously categorical, representing a history of crisis allocation rather than continuous investment in safety-net systems and disease prevention. This severely limits the flexibility needed to respond to an outbreak.

“We have a specific budget for tobacco prevention, a specific budget for obesity prevention,” Madera’s public health director Bosse said. “We have 78 (funding streams) for one department that all have to be tracked separately.”

The state allocated $12.3 billion to pandemic response in the past two years. Some counties have money left over or have staff hired to run COVID-19 clinics and conduct contact tracing, but haven’t been able to use them for monkeypox, which Elliott says they’ll need as cases increase in Tulare County.

The Legislature also approved $300 million in ongoing public health funding for local health departments in June, the first significant state investment since 2008. Typically that money would take several months to make its way to county health agencies, but the state of emergency has helped them get the money now, county officials said.

Still, county officials emphasize that spending flexibility is needed in public health. Riverside County Public Health Director Kimberly Saruwatari said the employees responding to monkeypox are working “outside of their grant requirements” and local departments won’t be able to sustain that spending. San Diego County Public Health Director Elizabeth Hernandez testified during Tuesday’s hearing that her department is spending $90,000 per week on monkeypox response and has incurred more than $400,000 in expenses.

Even with a more coordinated statewide response, bureaucratic delays and shortages at the federal level threaten to upend local efforts to control the spread. The CDC recommends doctors only test a small subset of the population that suspects they are a close contact of someone with monkeypox or are symptomatic. Also, the antiviral treatment for severe cases is considered experimental and requires hours of paperwork for each patient along with an ethics review, rendering most clinics unable to give it to patients. Meanwhile, vaccines remain far too scarce.

UCSF’s Dr. Chin-Hong said limitations on who can get tested mean cases are diagnosed far too late.

As of Aug. 2, the state health department had received 6,682 monkeypox test results, with the positivity rate around 19%. Generally, a positivity rate higher than 5% means not enough testing is being conducted.

“In an outbreak setting you want to test as many people as possible. You know you’re successful if you have a lot of negative tests,” Chin-Hong said.

The earlier a case is diagnosed, the easier it is to conduct contact tracing, which becomes critical in the face of vaccine shortages. That, however, continues to be an obstacle.

The Mercury News reported that San Francisco’s health department has largely abandoned contact tracing as a primary containment strategy — citing difficulties in getting patients to divulge sexual partners — and is instead telling people to “self-refer partners.” Monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted disease but has been spreading through sexual networks due to the close skin-to-skin contact needed for transmission. In comparison, contact tracing for COVID-19 quickly became infeasible in part because the ease of airborne transmission made it impossible for many people to pinpoint where they became infected.

Epidemiologists say monkeypox could feasibly be contained given its long incubation period of two to three weeks, but it requires public health departments to have ample employees to do the work of getting a detailed history from patients and calling every known contact.

“We don’t have enough money for robust contact tracing given the number of cases,” Chin-Hong said. “That leaves people to do their own contact tracing. They need to get tested.”

Elliot, Tulare County’s public health director, said most counties will have trouble scaling up contact tracing without state support. Her staff has three communicable disease investigators who work to find close contacts of each case and two public health nurses that are in daily contact with positive patients to monitor their symptoms.

“We have two cases but we’d be ignorant to think we won’t have more,” she said. “Eventually, we won’t have the bandwidth for this anymore.”

Los Angeles County Health Officer Dr. Muntu Davis said his department has “insufficient resources for contact tracing” and has requested help from the state. Confirmed monkeypox cases in Los Angeles County doubled in the past 10 days to 647 infections, Davis told legislators at Tuesday’s hearing.

With lackluster testing and contact tracing resources, Chin-Hong said the primary strategy for monkeypox containment becomes “vaccinate like crazy” for the most at-risk population: gay, bisexual and transgender men.

Yet again, that strategy comes with severe limitations.

“I want to be clear, the state of emergency and emergency budget request? Neither will solve our most basic need, which is for more vaccine. We can’t distribute a vaccine that we don’t have,” said Kat DeBurgh, executive director of the Health Officers Association of California.

Officials continue to stress that risk remains low for the general public, and some say the political discourse has caused unwarranted panic.

Monkeypox won’t infect as many people as COVID-19 due to its mode of transmission and has not caused any deaths in the United States, although it can cause painful lesions on the skin. Twenty-seven patients, representing 3% of all cases, are hospitalized in California primarily for pain management, according to State Health Officer Dr. Tomás Aragón.

In comparison, more than 4,300 COVID-19 patients are currently hospitalized and 93,056 Californians have died since the beginning of the pandemic.

“This is a self-limiting, non-fatal disease,” Solano County Public Health Director Dr. Bela Matyas said. “Here we are redeploying from COVID to monkeypox. COVID kills. Monkeypox doesn’t. And I think it’s fair to ask where the logic is in that kind of decision-making.”