The elementary school students in Kendra Hatchett’s summer school class in Compton are used to adults asking them questions. Teachers ask them questions in class and on tests; principals ask them questions in the office and in the hall.

But this summer, the tables were turned. Students interviewed teachers and coaches and even the principal.

“When we were interviewing the people, it felt like we were the bigger person now and they were the smaller person,” said 10-year-old Camilla Vasquez.

This was especially significant because in the past Camilla hasn’t always felt confident enough to speak publicly.

“Sometimes I’ll get put down, because I can’t really talk to people. I get nervous,” she said.

The journalism class for English learners is a creative approach Compton Unified School District in Los Angeles County is taking to help students become proficient in English faster. The district started the program about six years ago as an after-school journalism club, based on curriculum designed specifically for English learners by Loyola Marymount University.

“One of the areas English language learners struggle with is reading and writing,” said Jennifer Graziano, director of English learner services in Compton Unified. “Rather than having the same kind of interventions where they practice skills, we wanted to do something more innovative.”

Graziano said the district has seen growth in writing and other language skills among students who participated in the program in past years. The program won a Golden Bell Award from the California School Board Association in 2019. Last school year, the district couldn’t offer the program after school because of staffing challenges, Graziano said, so instead, they are offering a six-week summer program serving about 130 students.

Camilla and all the other students in her summer journalism class speak Spanish at home, and they’re working toward becoming fully bilingual. All the students in the program are in third through fifth grade, and most of them have been in school since kindergarten, but they still haven’t quite mastered the English language enough to pass the state’s English proficiency test. So they still need to take extra classes for English language development.

“We really don’t want them to leave elementary school and go to middle school still needing that much support from that department,” said Hatchett, one of two teachers in the journalism program for English learners this summer in Compton.

Research shows most students who speak a language other than English at home become proficient in English within about six years. But some students take longer. Students who have been in U.S. schools for at least six years but have not yet become fluent in English, and have not advanced in two years on the English language proficiency test are considered long-term English learners in California.

About 200,000 of the 1.1 million English learners in the state are long-term English learners. About 130,000 other students are considered “at risk” of becoming long-term English learners, because they have been enrolled in U.S. schools for four or five years and are scoring at the intermediate level or below on the English language proficiency test.

These students are at risk of missing out on academic content in middle school and high school classes if they don’t get extra support. They can end up behind in academic classes and be locked out of electives because they still have to take English language classes.

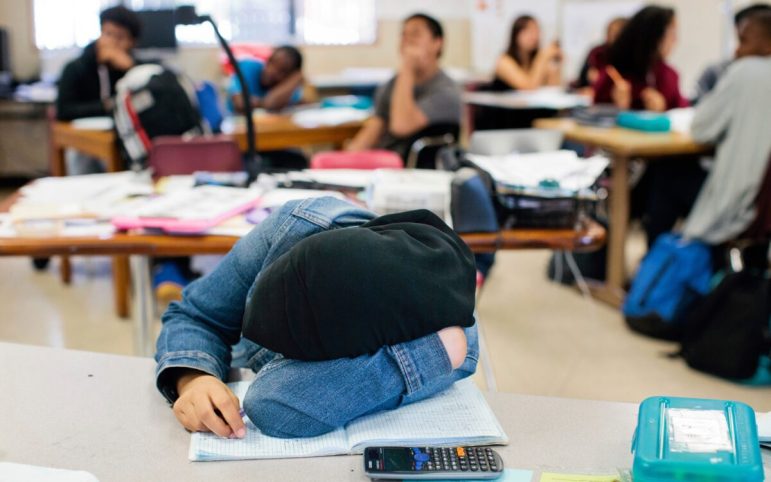

During the school year, Hatchett teaches fifth grade, and she sees many of her students who are English learners struggling with speaking and participating in class.

“Even those who are fluent, you know, in terms of speaking, often kind of shut down and just don’t really want to try it, even though they have the ability,” said Hatchett.

Experts have been urging school districts to do more in the years prior to middle school to help students become proficient in English earlier so they don’t become long-term English learners. At the same time, experts say districts need to make sure they are giving English learners access to rigorous content, in addition to English language.

Journalism class does both, and it’s a particularly useful subject for English learners. To be a journalist, you have to hone skills like listening, speaking publicly, communicating clearly, reading and summarizing, and writing —the same skills you need to learn a language.

“Also, it’s a fun way for students to learn,” Hatchett said. “So it feels fun. They don’t feel like, ‘Oh man, we’re doing work.’”

The summer journalism classes are small, with groups of eight kids each, which helps Hatchett give each student more one-on-one attention and helps the students feel more comfortable and confident speaking in front of others.

“That’s the first thing. You don’t have as many students you’re taking a risk in front of,” Hatchett said. “Number two, I’m really pushing you more than probably the average teacher that’s got 34 students and has seven subjects to teach.”

In big classes, Hatchett says, “If the quiet ones don’t speak, then they just don’t speak. In my case, everybody has to interview at least one person. And I am making speaking a big component of instruction.”

First, Hatchett brought in some local newspapers, both in Spanish and English, including La Opinión and the Los Angeles Times, for the students to read.

Then, she focused on practicing the language, by teaching the students the fundamental journalism skill of interviewing.

“I was teaching them listening comprehension skills. That’s number one,” Hatchett said. “That was a big thing to get them to take notes and to listen to what I’m saying. You gotta keep up with me ‘cause I go fast.”

The students decided together whom they wanted to interview. This summer, students interviewed teachers, a principal, a coach and a group called Team Kids, a nonprofit organization that visits schools to “empower kids to change the world,” according to its website.

Hatchett gave the students examples of questions they might ask a source, and then the students worked with their peers to come up with questions of their own. Then Hatchett reviewed the questions with the students, to really dig into grammar. She had them read their own questions out loud and asked, “Now, how did that sound? Did that question sound clear to you? Do you think you conveyed what you were trying to ask? No? OK, let’s fix it together.”

Before sending them out to interviews, Hatchett had them rehearse. She would pretend that she was the person they were going to interview, and they had to practice asking her their questions.

“One of the hardest things for everybody was actually articulating your question, whether they were a strong reader or not, because of the confidence,” Hatchett said.

Overcoming a fear of speaking in front of other people — having more confidence — is highly significant for students learning English. It can erode a student’s confidence to be told year after year that they haven’t learned English. Many such students learn to be quiet and stay under the radar. Sometimes in big classes, these students are overlooked and don’t get the attention they need.

Hatchett’s students said they were nervous before conducting the interviews.

“For me it was new, because I haven’t interviewed somebody ever. So I was nervous because I was interviewing people, and this is my first time interviewing people,” said Alison Mendez, 10.

Adrian Espinoza, 10, said it was hard because the room was so quiet.

“Having all that silence kind of got me nervous ’cause I’m used to loud noises,” he said.

Once they completed their interviews, they wrote articles about the people they interviewed, and they’re publishing them in an online newspaper. They also recorded a video news broadcast.

The students said they loved the class and learned a lot, especially in English skills.

“I have learned how to come over my fear of talking to someone on camera,” said Alison. “I’ve learned more about how to speak correctly … and I learned how to make my writing better and more exciting.”

“I’ve been learning how to type fast and how to think of new ideas every day,” said Ayleen Andrade, 10. “I stuttered a lot and now that I’m interviewing, I am feeling very confident and better with my words.”

“My English was kind of horrible, but now since we type a lot of stuff and talk about a lot of stuff and interview people, I learned how to put more vocabulary inside of my English,” said Camilla.

Hatchett’s students say they are going to use these skills in fifth grade this fall. In the future, they have dreams of becoming teachers, lawyers, doctors or managers of a big company. Adrian said there was a 60% chance he might even become a journalist.