Despite enrolling more low-income undergraduate students than any other University of California campus last year, UC Riverside is also the least-funded UC campus.

UC Riverside gets $8,600 in state support for instruction of each student, well below the systemwide average of around $10,000.

Fewer out-of-state students — who pay about three times more in tuition than in-state students — choosing to attend the Inland Empire campus is a key reason for the disparity. All told, UC Riverside generates about $6,000 less in revenue per student than the other UC campuses when factoring in the two main revenue sources — state support and tuition revenue.

UCLA and UC Berkeley lead all campuses with more than $29,000 in revenues per student from those sources. UC Riverside brings in about $21,000. The financial disparity data comes from a UC Riverside analysis of 2018-19 UC systemwide figures. The data excludes information about UC Merced and UC San Francisco because those campuses are funded differently.

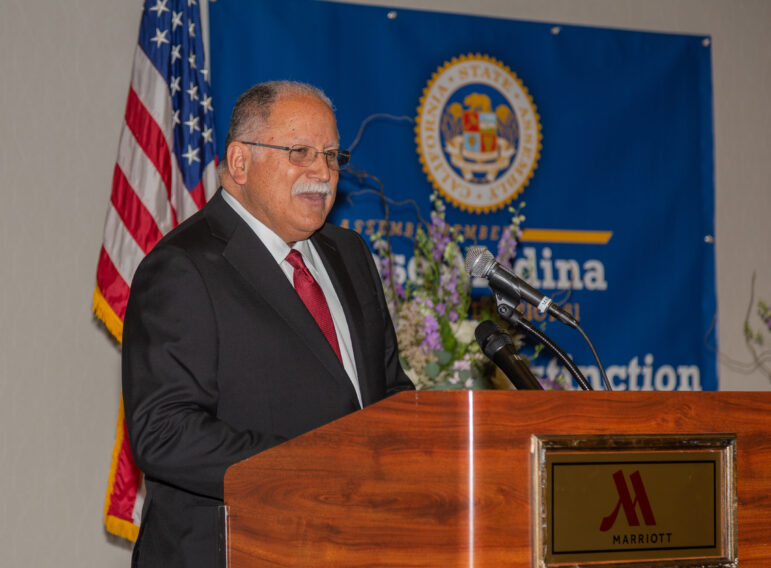

The Legislature, driven in large part by Assemblymember Jose Medina, wants to help the campus make up the difference with as much as $790 million in one-time funding and $80 million annually.

The university’s supporters are now waiting to see if Gov. Gavin Newsom agrees.

The Legislature is pushing to include hundreds of millions of dollars for UC Riverside and several other campuses with historically less funding in the upcoming state budget that’ll begin July 1. Leading the effort is Medina, a Democrat from Riverside, who’s in his final term in office and has marked additional funding for UC Riverside as one of his two legislative priorities this year, in addition to expanding student financial aid across the state.

To underscore UC Riverside’s funding woes, Medina held a press conference in June outside a movie theater that for nearly 25 years UC Riverside has leased as classroom space for courses with large enrollments. The Inland Empire campus is short 4,700 classroom seats for students, while UCLA and UC Berkeley have more seats for instruction than they need.

But UC Riverside’s money problems have less to do with state support than how the UC system distributes state dollars to the individual campuses, which is based on a formula UC Riverside says is unfair. Another UC rule further leads to a funding gap between the other UC campuses and UC Merced and Riverside: The system allows campuses to keep all their revenue from non-resident students. Because the two inland campuses enroll a far smaller share of non-resident students than do the other campuses, they get relatively less money from tuition revenue.

Are those good reasons for the state to supply UC Riverside and Merced with more dollars?

Medina said yes. “It will be an economic stimulus for our area,” he said in an interview with CalMatters.

And funding for specific campuses has precedent. Last year lawmakers injected nearly $500 million to transform Cal State Humboldt into a polytechnic university. Medina himself pushed hard to secure annual state funding for UC Riverside’s school of medicine a decade ago.

Medina added that additional state support will make up for past underfunding.

The state does have an interest in promoting social mobility, said Kevin Cook, a higher education researcher at the Public Policy Institute of California, a nonprofit research group. Investing in UC Merced and UC Riverside makes sense from that perspective given their track record of enrolling higher percentages of low-income students and students of color than the rest of the UC system.

“Those campuses serve students in the Inland Empire and up in the Central Valley and that’s a key area for the state to focus on demographically, “ said Cook.

Both areas have lower levels of adults with college degrees than the rest of the state, according to California Competes data. But the regions are also expected to have a higher share of the state’s K-12 public students by decade’s end as enrollment in other parts of the state drop off considerably. Adding enrollment capacity at the two UCs to educate those students “makes a lot of sense” for the state, Cook said.

Medina originally sought $1.46 billion for UC Riverside and UC Merced in a bill. Almost all of it would be for campus construction projects and other facilities to expand job and research opportunities near the campuses. That bill also wanted to give the two campuses $157 million in ongoing funding, money that could go toward hiring the some 700 staff and 100 faculty UC Riverside says it needs to hire to be on par with UC system averages.

Among the missing personnel are college mental health counselors, academic advisors and financial aid officers who can guide UC Riverside’s higher share of low-income students through the complex web of state and federal aid, said Gerry Bomotti, UC Riverside’s chief financial officer.

So far the Legislature is on board partially with supporting Medina’s plans. On Monday lawmakers approved their version of the state budget that begins July 1. It includes $83 million for campus expansion projects at UC Merced and UC Riverside plus a promise to send $249 million overall in the next three years. Additionally, $185 million combined in climate initiatives would go to UC Merced, UC Riverside and UC Santa Cruz, another relatively underfunded campus.

There’s no deal in place to send additional “ongoing” state dollars to UC Merced and UC Riverside, which will make it difficult to hire more staff. Still, both campuses would benefit from added ongoing money lawmakers want to send to the UC system overall plus another plan the UC system has for increasing UC Riverside’s share of state dollars.

Medina considers the extra money in the budget the Legislature passed a victory for the inland UC campuses. Despite a state budget surplus of $100 billion, Newsom and lawmakers want to commit only a tiny share, less than 10 percent, for new, ongoing spending.

Newsom hasn’t signed off on this plan, which departs somewhat from his own higher-ed proposals. A budget deal among the governor and legislative leaders is likely to occur in the next few weeks.

The UC system has begun increasing UC Riverside’s funding so that the amount it gets per student is almost equal to the average of the other campuses — known as the “unweighted” student funding average in UC fiscal parlance. The plan is to raise UC Riverside’s funding to roughly $20 million a year more by 2023 than the campus would get from the system’s funding formula alone. It received an initial $6.7 million more last year. A similar plan is underway for UC Santa Barbara and UC Santa Cruz; the two campuses last year got an extra $10 million combined.

Medina’s bill is still alive, though a committee amended it to include funding only if lawmakers and the governor agree to its full bill. Bomotti of UC Riverside said no one expects that all the money the bill seeks will end up in the budget, but the bill underscored the “catch up” in funding the campus needed.

The PPIC’s Cook said Medina’s bill has another advantage for UC Riverside. Because much of the money is meant for building instructional space for the health sciences, that would allow the campus to enroll more health science students, who generate more revenue than other students under the UC system’s funding formula for state dollars.

So not only would the region potentially see more college graduates in high-demand fields, it would also exploit a funding formula that for now rewards campuses with more health science students.

“It seems like a win-win-win,” Cook said.