Members of California’s Air Resources Board today questioned the practicalities of their staff’s proposal to ban gas-powered vehicles, raising concerns over challenges in buying and charging electric cars.

Air Board Chair Liane Randolph asked staff to find more strategies to ensure that the state’s proposed mandate includes strong equity measures so that low-income residents face fewer barriers buying electric cars.

At a public hearing that stretched on for nine hours in Sacramento, auto company representatives, environmentalists and car owners showed up in droves to voice their concerns. Some said the rapid transition could harm the disadvantaged communities it aims to help, while others said the air board needs to take bolder action to address air pollution.

The rules would mandate increased sales of electric or other zero-emission vehicles in California, beginning with 35% of 2026 models. In 2035 sales of all new gas-powered cars would be banned. Currently only about 12% of new car sales in California are zero-emission vehicles.

The standards would be among the most aggressive actions that state regulators have ever taken to address climate change and poor air quality. They could transform the cars Californians drive, revolutionize the auto and power industries, and could eventually drive stronger nationwide standards.

“This is arguably the most important action the California Resources Board will ever take,” said Daniel Sperling, a member of the Air Resources Board and founding director of the University of California, Davis Institute of Transportation Studies. “What we’re doing here is by far the most important strategy for decarbonizing transportation. There’s nothing even close to it.”

Air board member Diane Takvorian, who is executive director of an environmental justice group, said there is “a lack of clarity” about what the regulation can do, adding that it needs to address the availability of electric cars in the used car market. She said a steady and reliable supply of used electric vehicles is a necessity for low and middle-income residents.

She said the proposal needs stronger equity measures.

“If we don’t create a market that is creating affordability, we’re going to end up in the same situation that we’re in now with housing, where there are many homes on the market that are just out of reach for most of California,” Takvorian said. “I don’t think that the equity provisions that we’re talking about are necessarily that everybody in the state should be able to buy a new zero-emission vehicle. We need to figure out what the entire system looks like.”

The board is expected to vote on the mandate in August.

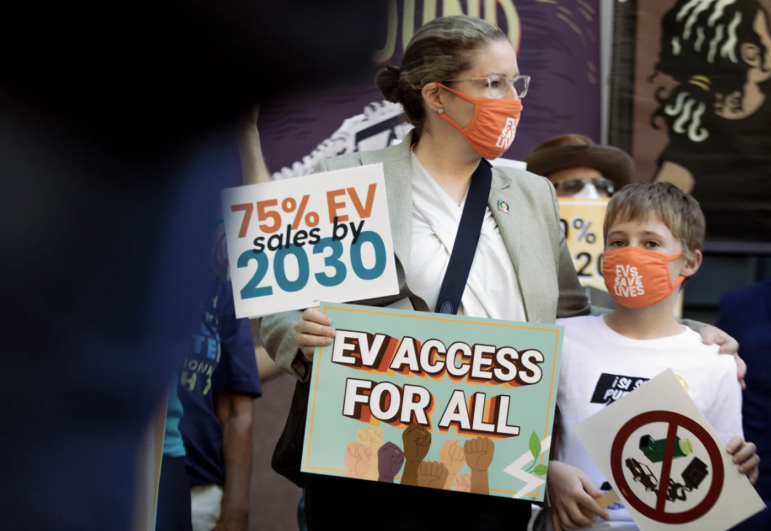

Environmentalists voiced concern that the board’s proposal doesn’t go far enough to get gas-powered cars off the road, urging the board to set a more stringent goal of 75% zero-emission sales in 2030.

Several city and county elected officials from around the state, including from car-centric cities like Long Beach, Santa Clara and Los Angeles, also expressed support for more stringent measures.

Representatives of automakers, including Ford and Subaru, said the industry is committed to electrifying its fleet, but raised questions about the timeline.

“Subaru fully supports an electric net carbon net zero carbon future, but today’s advanced clean cars proposal aims to set a very challenging path for the U.S. auto industry,” said David Barker, environmental activities manager for North American Subaru.

“There are very real challenges in meeting consumer demand while at the same time overcoming supply chain disruptions and limited access to critical help. These challenges are amplified for small manufacturers like Subaru.”

Dr. John Balmes, a longtime member of the air board and proponent of clean air, expressed concern about whether car manufacturers would be able to comply with the mandate.

“Do we have enough knowledge? I think the answer is probably no,” he said. “I’m worried that we’re not going to get the new zero-emission vehicles that we would like to have.”

Costs of the mandate could run $289 billion over the lifetime of the rule. But the economic benefits could reach $338 billion — a net benefit of $48 billion, according to air board staff.

While electric cars currently cost more than a gas-powered car, savings on gas and maintenance could end up saving car owners an estimated $3,200 over ten years for a 2026 car compared to a gas-powered car and $7,500 for a 2035 car, according to the air board’s estimates.

Air board staff say the new standards will boost interest in electric vehicles and bring the cost down over time.

But they said challenges with the transition remain.

Air board officials said consumer reluctance remains a concern, citing challenges that could hinder the pace of switching over to electric vehicles.

Also, the need for more public charging infrastructure and home chargers is already a barrier that is frustrating for some electric car owners. About 1.2 million chargers will be needed for the 8 million electric cars expected in California by 2030, according to staff’s calculations.

Car buyers are also concerned about battery life, higher purchase price and the limited number of models.

To address some car owner concerns, the proposed measure requires automakers to set strong performance, warranty and durability requirements. Electric cars must be able to drive at least 150 miles on a single charge. Batteries would need to be more durable and carry a manufacturer’s warranty. At least 80% of the original range must be maintained over 10 years. To ease the strain on automakers, that requirement would be reduced to around 75% during the first five years.

Air board staffers said they would grant automakers incentives to sell some vehicles at a lower cost in an effort to help low–income residents afford electric cars.

Under the proposed rule, automakers could get credits toward meeting their sales targets through 2031 if they sell cars at a 25% discount through community-based programs, or if they offer passenger cars for less than $20,000 and light trucks for under $27,000. Air board officials said provisions would prevent companies from stockpiling credits that would be a disincentive from meeting future requirements.

But some residents told the board that they’re already feeling financially strapped and can’t see ever affording an electric car. While the proposal offers financial incentives for automakers, they doubted they would gain access to programs meant to help low-income car owners.

“I am lower class. I am under the poverty level,” said Sherry Chavarria, a Dinuba resident. “How can I afford a Tesla? The people that get the incentives are the upper class.”

The rules would not apply to the used car market, and it wouldn’t eliminate the millions of gas-powered cars already spewing planet-warming emissions and smog-causing gases on the road.

The proposal would also drive a wide-ranging transition of the workforce, causing some industries to gain jobs while others lose them as the state shifts to pollution-free cars.

Throughout the economy, an estimated 64,700 jobs will be lost because of the mandate, according to the California Air Resources Board’s calculations. On the other hand, an estimated 24,900 jobs would be gained in other sectors, mostly in the power industry, so the estimated net loss by 2040 is 39,800 jobs, a minimal amount across the state’s entire economy.

Mechanics would be among the most affected — more than half of their current number of jobs would be lost over the next two decades if the mandate goes into effect, the air board estimated.

“I am sensitive to the fact that this rapid transformation will be disruptive across many industries, not just the auto industry, not just the oil industry, you’ve got the parts suppliers, you’ve got the mechanics, you’ve got the electric utilities, you’ve got the local governments,” air board member Sperling said at the hearing. “And it’s going to be even more disruptive in the other states who lag behind California in every way.”

Sperling said it’s important that California sets a strong precedent and reduces the challenges because other states will follow suit.

“My biggest concern by far is dealing with the other states, and we need them to be successful because what we’re doing here is not just for California,” he added. “If you look at it from a climate perspective, actually, this is much more important.”

At a rally at the air board’s headquarters in Sacramento before the hearing, environmental justice advocates called on the board to take bolder action on the mandate.

Meg Whitman, 42, a Sacramento-based physician at the rally, moved to the area five years ago from Massachusetts. She said her seven-year-old son was diagnosed with asthma last year, which she thinks could be from exposure to wildfire smoke and exhaust from highly-congested freeways.

“He really didn’t have any symptoms of asthma as a baby and during his toddler years,” she said. “We are going to keep a close eye on it, but we have considered moving out of the area for his sake. The question is, where is that and where will it be safe?”

Whitman’s three-year old son also came down with bronchitis as a six-week old baby. While he has been healthy since, she said she’s now worried he could also develop asthma.

“The faster we can curb tailpipe emissions, the faster we can help prevent some of these diseases and excess deaths,” she said. “It’s just something I think about with my boys all the time. I’m frightened for their future. My boys, they’re just my whole world.”

The air board’s move toward zero-emission vehicles has been decades in the making. But many of those efforts have also faced hurdles.

California first adopted zero-emission standards in 1990, which at the time required that 2% of new car sales between 1998 and 2000 be emission-free, and increase to 5% in 2001 and 2002. In a stunning reversal, the air board rescinded those rules in 1996 following immense pressure from automakers and oil companies. At the time, concerns over the technology and battery lifespan of electric cars fueled much of the debate.

Today auto companies like Tesla and Ford have transformed the state’s electric vehicle market, with more than 80 models now available.

Only about 2% of the state’s 26 million cars on California’s roads were zero emissions in 2020, but electric vehicle sales have been steadily increasing since. The state had formerly enacted standards that required about 8% of new cars sold in the state to be zero emission in 2025, according to air board staff. That goal was already met in 2021, when electric vehicles made up 12% of all new car sales.

The state has long been a pioneer in setting tough climate change policies and the federal government usually follows. At least 15 other states have pledged to follow California’s lead on bold auto emission rules.

Many representatives from several states, including New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Oregon, showed up at today’s hearing in support of the proposal, vowing to implement similar rules in their states.

The transportation sector is one of the largest sources of pollution across the state, accounting for about 40% of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The state’s authority to independently set stronger tailpipe emissions standards and mandate zero-emission sales was granted half a century ago, when Congress passed the Clean Air Act in 1970. The law included special conditions for California to help the state address its severe smog.

Under President Donald Trump, the state’s authority was revoked by the Environmental Protection Agency. The state then filed lawsuit after lawsuit to overturn the decision. California and four major automakers also made their own deal to continue cutting greenhouse gases.

The Biden administration in March restored the state’s power to set emission standards stricter than the federal government’s. That decision is now being challenged by 17 Republican state attorneys general, who are suing the administration for what they say is “favoritism” that “violates the states’ equal sovereignty.”