Edith Kiertzner’s family lost their Iowa farm in the 1920s, and the family china set was one of the few things they kept. We can imagine the Great Depression scene like a movie: Edith, her parents and six siblings, wondering what’s next, their white porcelain china set in a box, ready to serve Sunday-best meals that no one could afford anymore.

Later in life, Kiertzner, who married Brian Heath in 1938, would become a ceramicist and describe white porcelain — the material those dishes were made of — as “gutless.” She rebelled against the refined material that had been stripped of its character and texture. And she rejected everything it stood for — imported affluence and preciousness that people reserve for special occasions.

Edith Heath would create dishware designs in the 1940s with richly textured California clays and blaze a trail that still burns today. In fact, it’s possible that the dishes you just bought were inspired by Heath’s aesthetic and California sensibilities.

The Oakland Museum of California brings Heath’s artistic process and entrepreneurial spirit to life in “Edith Heath: A Life in Clay,” on view until Oct. 30. The exhibition is much more than a collection of dinnerware — it’s a fascinating creative journey that has something for everyone.

Want to geek out on how clay comes out of the earth and see what makes California clays unique? Check. Want to follow Heath’s ascent from a ceramicist who created one-of-a-kind pieces to an entrepreneur who turned the housewares industry on its head? Check. Want to swoon over modern lines and get a whiff of inspiration? Check, check!

The show is organized by Drew Johnson, OMCA curator of photography and visual culture, and guest curator Jennifer Volland, an expert on Heath’s life and work. Quotes emblazoned on the walls throughout the exhibition help tell the story. And a detailed timeline walks visitors through Heath’s difficult childhood, her teaching jobs, her marriage and all the years when she was at the right place at the right time.

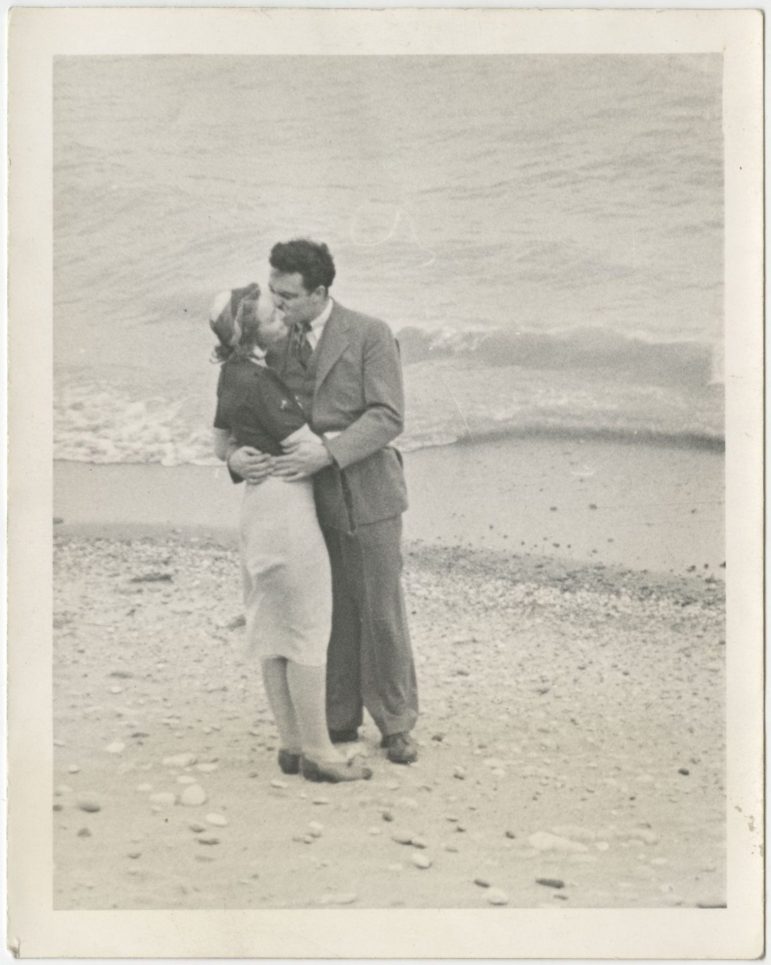

Edith and her husband, Brian, made a life-changing move to San Francisco in 1942, following Brian’s job as an American Red Cross regional director. Edith took ceramics classes at the California School of Fine Arts, taught at the Presidio Hill School in San Francisco and, in 1943, started researching clays and glazes.

Edith had the mind of a scientist and inventor, and war shortages sparked her search for new materials to make her art. She and Brian spent weekends driving around California looking for clay in the landscape, show curators say.

“With many mining operations closed during the war, she was not able to get the materials she needed to practice ceramics,” Volland says. “So the couple would find defunct clay pits and gather materials, including brick clays from Niles Canyon in the Bay Area, talc from Southern California, and fire clays from Ione in the Sierra Nevada foothills. The latter, Ione, was the origin of the first clay Heath Ceramics used in its production clay body.”

Edith knew she was breaking the mold, and she relished it. She had embraced California’s casual lifestyle and modern sensibilities.

“What I do is going to change things,” she said. “Things aren’t going to be the same anymore.”

World War II dragged on, and imports of household ceramics stopped. Edith’s big break came circa 1944-’45, when Gump’s department store buyers discovered her ceramics exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco.

Impressed by her modern aesthetic, Gump’s buyers asked her to create a line of dinnerware. Heath used a speckled California clay body, leaving ultra-fine, white porcelain in the dust. Heath Ceramics — and Edith and Brian’s commercial enterprise — was born, and the conversation around what ceramics could be completely changed.

In 1947, Heath Ceramics moved into a factory in Sausalito and started producing dinnerware that would go far beyond California. The Heaths were going national. The ceramics establishment balked and called Edith a “sellout.” But consumers had the last word, and Heath Ceramics, based in Sausalito, is still in operation today.

“The fun part was she was constantly exploring,” said Winnie Crittenden, a Heath Ceramics employee since 1974. “Stacks of seconds would pile up and just wouldn’t sell. So she and I worked on pouring glazes across them, and we’d have one-of-a-kinds. And eventually, we ended up with this series of landscape plates.”

One of the exhibition’s displays presents her earthy, modern dishware alongside her mother’s elegant, pristine china set. It’s like a “before and after,” where we can see just how much Heath rejected the attitudes and aesthetics she had grown up around.

“People here are much more easygoing, more humane and less concerned about status,” Heath, who died in 2005, once said about California. “I was trying to do something that was more egalitarian rather than aristocratic. Not ‘Art’ pottery — functional dishes.”

“Edith Heath: A Life in Clay” runs through Oct. 30 at Oakland Museum of California, 1000 Oak St., Oakland. The museum is open 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesdays-Sundays. Admission is $16 adults, $11 seniors, $7 youth ages 13-18 and free for children age 12 and under. For tickets and more information, visit https://museumca.org/.