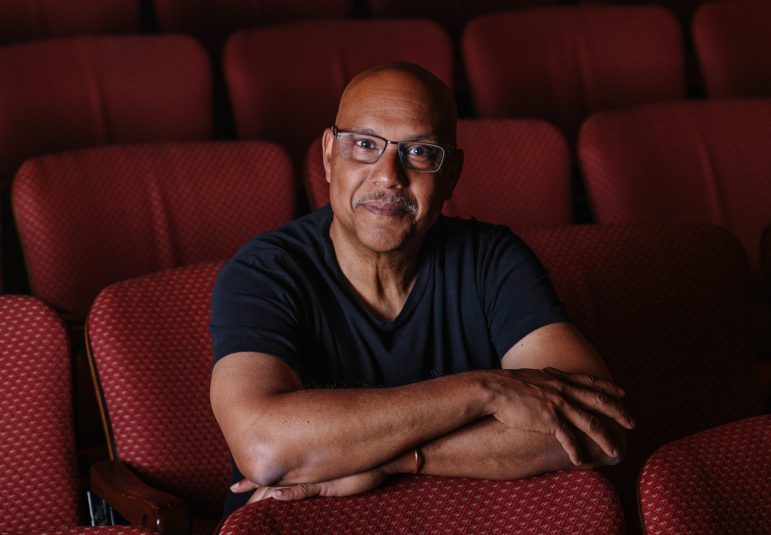

When Tim Bond, artistic director of TheatreWorks Silicon Valley, first started directing in the ’80s, clashes over the apartheid were raging in South Africa. At the time, he was working on several plays that dealt with discrimination and segregation.

One of the plays he directed — written by a South African playwright — was staged at a school in Seattle. He recalls that it was transformative for the students at the school. Inspired by the play, the school held bake sales all year long to collect money for children at a school in South Africa.

Bond says such reforms owing to the theatrical arts happen across society. Seeing a play “can lead to that sort of activism, or it can just lead to people treating others around them in kinder ways,” he says.

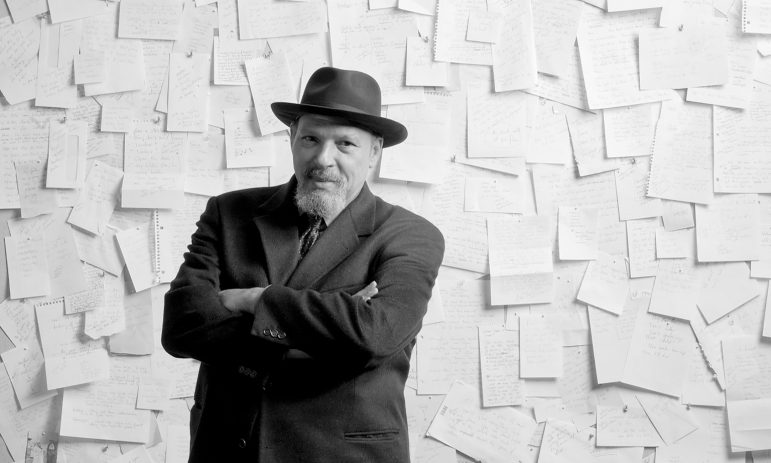

A soul-stirring theatrical experience of the kind Bond describes is going to entertain Bay Area audiences starting this week at Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts in Mountain View. Set in 1904 against the stormy backdrop of police violence and rioting, “Gem of the Ocean” — conceived by the late August Wilson and now being produced by TheatreWorks — is relevant and poignant even now, more than a hundred years after the story takes place. Following a 2003 premiere production at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, “Gem of the Ocean” ran on Broadway in 2004 and 2005, where it was nominated for five Tony Awards including Best Play.

It is the ninth play in the acclaimed “American Century Cycle” of 10 plays by Wilson. Each of these plays explores one decade of the African American experience during the 20th century. The cycle includes groundbreaking works about the African American experience — “The Piano Lesson,” “Fences,” “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” “Jitney,” to name a few — and Wilson’s literary genius was consistently lauded as nine of the plays on Broadway received Tony Award nominations for Best Play and two also won the Pulitzer Prize.

Bond is on a personal mission to complete the cycle of Wilson’s plays and has just three more to go. He was a friend of Wilson’s, and he feels honored to be able to present his words on the stage. Wilson’s early death at age 60 in 2005 was a great loss, Bond says.

“It was a tremendous loss to the world, to the field of theater, and for me, personally, because I looked up to him profoundly — as an artist, as a man, as a person on the planet who carried an energy and a wisdom and a body of knowledge,” he says.

“Gem of the Ocean” will connect with the diverse community in the San Francisco Bay Area because the play, most of all, is about family and community. It asks questions about the meaning of freedom. Beyond the cast itself — Greta Oglesby was the actor August Wilson originally envisioned in the role of 285-year-old Aunt Ester — Bond says that the music is riveting. It’s a layered play that’s also laced with humor.

Above all, he says, the production will appeal to the intellect because of its topicality in an America that’s currently more untied than it is united. All the social inequities “Gem of the Ocean” grapples with in the year 1904 are still prevalent in the America of 2022. The play raises all sorts of questions about our society regarding police brutality, criminal justice reform, systemic racism and social inequity that are valid today.

Among the most moving moments of the play is when Garrett Brown, who’s falsely accused of having stolen a bucket of nails at the local mill, decides to jump into the river. He didn’t steal the nails, but the authorities won’t believe him. He decides he cannot take one more breath of air and drowns. Death itself is more welcome than the ignominy of a false accusation. “Gem of the Ocean” tells us, in the character of Caesar, the Black law officer, that he, too, is as guilty as those he accuses of theft, vandalism or murder.

The Black Lives Matter movement didn’t exist 15 years ago, when Bond first directed “Gem of the Ocean” at the 2007 Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland. Today, non-Black theatergoers are more likely to be aware of the issues raised in the play and how they still impact modern society, thanks to BLM.

”The reality is we haven’t come far enough,” Bond says.

But more people in America from all backgrounds have awareness about systemic and institutional racism than they did even two decades ago, especially now that most people have handheld recording devices, in the form of smartphones, and the ability to post live video on social media. “We have footage now on cameras that [is] indisputable about the treatment of Black bodies by the police,” Bond says.

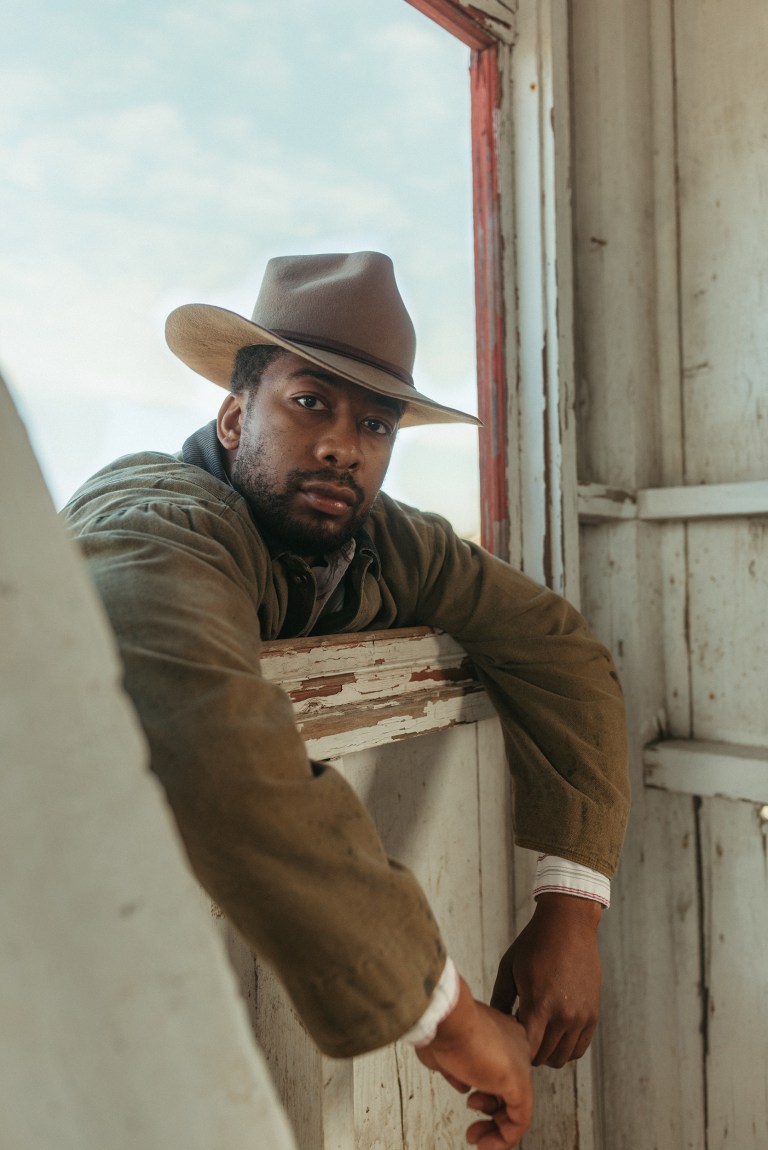

“Gem of the Ocean” underscores how much more we still need to do as a nation. In the play, after Garrett Brown drowns himself, a young Black man, Citizen Barlow, is desperate for redemption. He visits Aunt Ester, the community’s spiritual advisor and keeper of collective memory, and she takes him on a supernatural voyage aboard a slave ship where he learns his ancestors’ history.

Citizen’s journey from guilt to redemption is depicted masterfully as the other, larger, spiritual journey that each African American has to experience over the course of his life. This, suggests Wilson, is the journey through the Middle Passage — leaving Africa and coming to the Americas. It’s one that every Black man carries deep in the recesses of his brain. The old, old Aunt Ester represents the crucible of those memories — of chains, torment and hurt. The bottom of the ocean contains the bones of enslaved people thrown overboard or of those who died by suicide. Citizen’s journey then is a spiritual crossing of sorts from hurt and insecurity into self-confidence and hope.

The year 1904 is exactly 285 years after 1619, the year a ship appeared on the horizon at a coastal port in Virginia carrying more than 20 enslaved Africans. Aunt Ester’s address — 1839 Wylie Ave. — is significant, too, notes Bond; it’s the year of the Amistad Rebellion, when enslaved people aboard the eponymous ship revolted and attempted to divert the ship back to the African coast.

“Gem of the Ocean” makes us question all the values we hold dear. Through the voice of Solly Two Kings, an old man who is a suitor to Aunt Ester, we begin to reflect on what freedom and independence actually means in our own lives. Solly says his father wanted freedom but didn’t have it. But he, Solly, has it but still doesn’t know what it is. “It ain’t never been nothing but trouble,” he says. “I seen many a man die for freedom, but he didn’t know what he was getting. If he had known, he might have thought twice about it.”

Throughout this play, the omniscient Aunt Ester can be both mordant and reassuring. Her preachings to Citizen Barlow on love and compassion are a classic for these times when differences in gender, race, faith and politics threaten to drive us all apart. She says, “The people will come and tell you anything. They got all kinds of problems. They tell you this and they tell you that. You’ll come to find out, most of the time, they are looking for love. Love will go a long way toward making you right with yourself.”

The power of theater as cathartic and transformational is nothing new, and TheatreWorks’ artistic director looks back at the events in the school in Seattle in the ’80s. The staging of the play, as well as an accompanying workshop on apartheid, raised the level of consciousness among students, some of whom went to South Africa to participate in an anti-apartheid movement.

Years later, Bond received letters from several former students at that school saying that the play had even steered them toward their careers.

“Theater has been reforming societies for thousands of years in all sorts of ways, both subtle and striking,” he says.

Most of all, it helps people have a greater understanding of themselves.

That’s why we all need to show up at the theater in droves, in order to receive the collective wisdom of the ages, to be inspired, to see ourselves reflected on stage, both in our uniqueness and, of course, in our similarities.

Bond gives voice to the role of theater in his lyrical way: “It helps give us a better understanding of our human condition, for we’re in this together as a big family.”

TheatreWorks Silicon Valley’s production of August Wilson’s “Gem of the Ocean,” directed by Tim Bond, runs through May 1 at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts, 500 Castro St., Mountain View. For information and tickets, visit https://theatreworks.org/.