California wants to lure all 4-year-olds to public schools within the next four years. But will there be enough teachers there to meet them?

School districts across the state are scrambling to hire an estimated 11,000 teachers and 25,000 teacher assistants to expand transitional kindergarten. It’s a tall order for school district officials already in the midst of a daunting educator shortage and coming out of the pandemic.

“If we can’t find staffing, we just flat can’t do it,” said Mike Martin, superintendent of the County Office of Education in Modoc County.

“It’s not like we have a pool of folks lined up asking to come to work in our districts. We are competing with everybody else out there for these same folks.”

The main potential source for these thousands of public school teachers are already teaching pint-sized kids in early childhood education. So now private and nonprofit preschool and child care providers are worried about losing not just 4-year-olds, but also their qualified teachers and staff members to the higher wages and free summers that public schools offer.

Their solution: A bill in the Legislature that would extend the state-funded expansion to their childcare centers and preschools for all 4-year-olds.

Gov. Gavin Newsom touts the expansion as a way to close the achievement gap and included $600 million in the 2020-21 budget, growing to $2.7 billion in the general fund by 2025-26. The budget also includes $130 million for student access and $300 million for planning and teacher training in one-time Proposition 98 money. A related policy bill flew through the Legislature and Newsom signed it.

The roll-out begins this fall for kids turning 5 between Sept. 2 and Feb. 2. Each year, more children will be able to enroll based on their birthdates until 2025-26, when the program will be available to all 4-year-olds.

California is home to about 500,000 4-years-olds. One in five of those children are already in transitional kindergarten, known as TK. It began in 2012 for kids who turn five between Sept. 2 and Dec. 2. Previously, those children had been able to enroll in kindergarten at age 4, but then the rules changed limiting enrollment in kindergarten to mainly 5-year-olds.

Transitional kindergarten is optional; parents can still choose to stay in their private pay program or subsidized state preschool.

Advocates say the benefits of the expansion are two-fold.

Access to free transitional kindergarten will benefit children who qualified for subsidized child care but could not find a slot, and those who do not qualify for help but whose families can’t afford to pay for child care or preschool, said Patricia Lozano, executive director of Early Edge, a nonprofit advocacy group that supported the new law.

Also, moving 4-year-olds out of early childhood education — such as state preschool, childcare centers or private preschools — and into public school is designed to open up seats for younger children, especially in state-run preschool and federally-funded Head Start programs.

Now, state preschool serves only 32% of eligible 4-year-olds and 13% of eligible 3-year-olds, said Sarah Neville-Morgan, deputy superintendent of the state Department of Education.

The participation rate for transitional kindergarten is expected to be 75% to 80% of all 4-year-olds, Neville-Morgan said. That is roughly an additional 345,000 children once the program is fully implemented.

“We are leaning in,” Neville-Morgan said. “Having universal transitional kindergarten for all 4-year-olds opens up opportunities for all 3-year-olds.”

Lofty goals indeed, but these do not help solve the labor shortage facing school districts that is so dire that schools needed to start hiring 300,000 teachers a year since 2018 to get caught up.

Ultimately, California school districts will need to hire an additional 11,000 new credentialed teachers for transitional kindergarten classrooms and 25,000 to 26,000 teaching assistants, according to Berkeley Children’s Forum.

Minimally, this year the state will need at least 2,400 teachers to be able to serve the 58,000 new children expected to enroll in transitional kindergarten in the fall. The following year another 3,600 credentialed teachers will be needed, said Bruce Fuller, professor of education and public policy at UC Berkeley who heads the Children’s Forum.

“It’s a huge and hopeful experiment, and I think a lot rests on how school districts will respond,” Fuller said. “And, secondly, can the nonprofit sector turn on a dime and re-equip and adjust to this new market reality?”

Now, the state is allowing teachers with bachelor’s degrees and multi-subject credentials to teach transitional kindergarten. By August, those teachers will also need to have completed 24 units of early childhood education classes, or they will need to have a child development permit.

In addition to the teachers and aides already working in early childhood centers, this also creates an opportunity for paraprofessionals, such as teacher assistants, to consider moving into teaching, said Xong Lor, legislative advocate for the California School Employees Association, which sponsored the expansion law.

She said declining enrollment in schools, equal access for all 4-year-olds to access transitional kindergarten and the opportunity for career growth drove the union to back the proposal.

“Our members are being paid so low, so having that opportunity to advance themselves that is something that we are supportive of,” Lor said. “When you take a para out and they become a teacher, now you’ve created this vacancy. So we need assistance to make sure these positions are being filled.”

While some school districts will see some teachers moving from other grades into transitional kindergarten, the main source of new recruits may come from California’s early childhood education world. There are an estimated 31,000 teachers with bachelor’s degrees working with the under 5 set, said Hanna Melnick, senior policy advisor at the Learning Project Institute.

The Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at UC Berkeley published a study in August that found that early childhood educators are well-equipped to teach transitional kindergarten. It found that 49% of early childhood teachers have a bachelor’s degree or higher and among those 76% also have a child development permit at the teacher level or higher.

“It seems like a no-brainer that these people should absolutely be eligible to teach TK,” said Elena Montoya, senior research and policy associate at the UC Berkeley center. “We are hoping and encouraging that these pathways be made available to early educators that have the most experience working with 4-year-olds.”

And they could have incentive to move to public schools: The median hourly wage for kindergarten teachers is $41.86, or about $73,000 a year, while preschool teachers earn $16.83 an hour, or about $35,000 a year, according to the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at UC Berkeley.

The potential exodus, however, will impact early childhood education, where it’s already difficult to find teachers and assistants.

It may also leave behind those, especially women of color who stack the sector, without the formal schooling required to transition over, according to research from the Berkeley Center.

“The message for the rest of the sector and the workforce seems to be that California is focusing on TK and centering resources even if it disrupts the rest of the system,” Montoya said. “They talk about it as a package, but is it really a package if these are the consequences, destabilizing the rest of the system?”

That is why the center supports including current child care providers and preschool centers to reach the goal of expanded transitional kindergarten. It also recommends creating an alternative pathway to qualify as a TK teacher so early childhood education experience can be recognized and count toward a credential.

The new bill, SB 976, would require that private and nonprofit providers be included in the expansion to give parents choice and to ease the staffing burden, said Dave Esbin, executive director of California Quality Early Learning, an organization that advocates for private child care providers.

Incorporating non-profit and private preschools would create better quality, Fuller agrees.

“We don’t just want public schools to decide what quality pre-K looks like. We want to have a diversity of organizations,” he said. “That’s good for parents because they can find a Montessori pre-K or a heavily disciplined pre-K, a hippy-dippy learning through play pre-K. Parents can find whatever they want if we continue to fund a diverse array of pre-K organizations.”

State Deputy Supt. Neville-Morgan, however, said transitional kindergarten is focused in public schools because much of the money for the expansion is from Prop. 98 funds, which must go to public schools.

“One of the things we hope is that California gets to a place where we are not saying, ‘You are stealing or taking (teachers),’ but that we are all in this together in a shared way,” she said. “We know that teachers are the most important thing for our little kids.”

School districts have been providing transitional kindergarten for nearly a decade. Some have been providing it for even longer under different names. Long Beach Unified School District was offering what it called “Preppy K” before the state created transitional kindergarten, said Brian Moskovitz, assistant superintendent of early learning and elementary education.

Now, the district runs transitional kindergarten classes, as well as state preschool and federal Head Start programs. In addition to recruiting more teachers for next year, the district is also leveraging existing staff to make the expansion work.

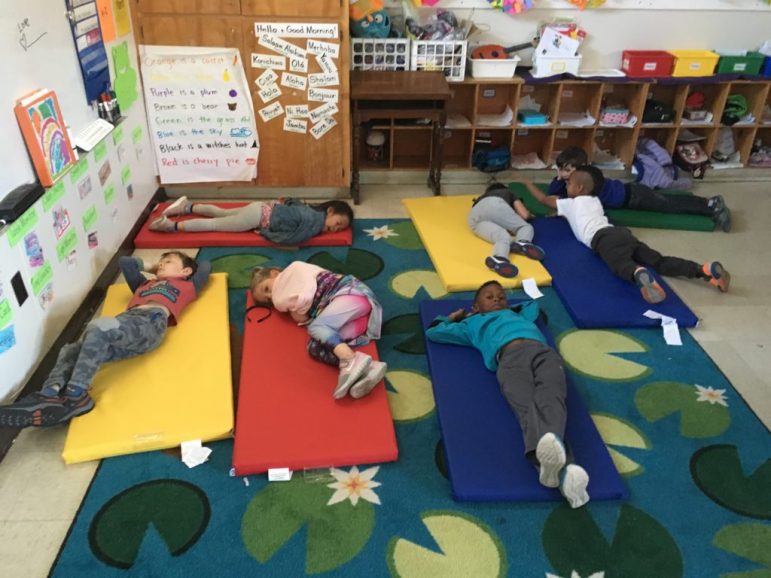

In one transitional kindergarten classroom, students who are in state preschool are combined with other transitional kindergarteners with the same teacher. The children are simply paid for by different pots of money.

In Humboldt County, officials are relying on a grant-funded residency program to train teachers on the job, but it’s going to take time, said Colby Smart, assistant superintendent of the Humboldt County Office of Education.

“We don’t have the level of qualified teachers to fill those positions,” he said. “This residency capacity grant is designed to plan and also to build the pipeline to get those teachers.”

The county will need 70 transitional kindergarten teachers. Currently, the county has 30 residents in training who should be fully credentialed by 2023.

San Diego Unified is a bit ahead of the curve. The district tested transitional kindergarten for all 4-year-olds this school year in 70 classrooms in its lowest-income schools, said Stephanie Ceminsky, who oversees early learning for the district.

“It’s such a special place. It’s not TK and it isn’t K and it’s not a 3-year-old,” she said. “4-year-olds are a special niche that early childhood educators do know.”

Next year, the district is rolling out the program across all campuses for all 4-year-olds regardless of birthday. Ceminsky estimates a need of 40 to 60 teachers for the incoming 3,200 students.

The district has most of its staff already because of the pilot program and plans a career fair in May.

In Modoc County, in the northeastern corner of the state, the three school districts serve a total of only 1,300 students. So combo classes with kindergarteners and even first-graders are the norm for 4-year-olds.

“We don’t have big enough number of students to justify the single classroom,” Supt. Martin said.

But Deputy Superintendent Misti Norby calls the combo classes “developmentally not appropriate.” So Martin and Norby will work closely with families to select the right placement, which may be staying in their current preschool setting.

Meanwhile, child care and preschool providers say they fear that they will lose staff and potential staff members, who will opt to go to school districts instead.

One preschool director called it “a slap in the face” after struggling to stay open during the pandemic to ensure little children got the care and learning they needed while public schools closed.

Many early childhood educators want to know: If the governor was going to dedicate money to kids under 5, why didn’t he bolster the early childhood system that already exists?

“All the statistics of the success of child care or preschool are based on our programs, Preschool is a cozy place with little child furniture and a teacher and a director,” said Holly Gold, who owns Rockridge Little School in Berkeley and two other locations that cater to 2 to 5 year-olds. “Now, they take all of that and they use it to jack all of the funds and divert them to public school systems because public school enrollment is down.”

At the Old Firehouse School in Lafayette, program director Alexandra Dutton said she doesn’t blame preschool teachers who may want to earn more money in public schools, but it worries her.

“They are going to get paid more, they are going to get vacation, they are going to have a union,” Dutton said. “I can’t compete with that. Most (private and nonprofit) schools won’t be able to compete with that, and that will directly impact the quality of early childhood centers because a lot of educated teachers are going to think about going.”

One of Dutton’s teachers is attending classes at night.

“She sees the writing on the wall,” Dutton said. “She is trying to get her bachelor’s because she’s realizing that things might change.”

CalMatters reporter Joe Hong contributed to this story.