Growing up in Oklahoma, Scottie Laird knew he was adopted. In fact, he and his parents used to laugh when people said he resembled them (which he does). But the three of them never discussed pursuing information about his birth parents.

It wasn’t until he was a student at the University of Oklahoma that Laird became curious and asked his adopted parents if there was any way to look for them. “I took some crazy courses that brought up interesting questions,” says Laird, now 53. “Like, what traits did I learn from my adoptive parents? And what traits would I share with my blood relatives?”

In 1987, Laird’s father suggested they take a weekend visit to San Antonio, Texas, where Laird was adopted. “We went to the courthouse in Bexar County,” he recalls. “They said we just needed to get a judge to sign a form and they could give me the information. I was surprised. This isn’t what I had seen on television—don’t people spend their whole lives pursuing this kind of thing?”

But sure enough, all Laird had to do was talk to a judge, confirm that he wanted the information and sign the form. He got the names of his birth parents —Charlotte Ellis of San Antonio, Texas, and John Hall of Colorado—and information including their occupations and physical descriptions.

A follow-up trip to the adoption agency wasn’t as fruitful. The agency staff wouldn’t release the first names of half-siblings that were on file. The organization did maintain files where birth mothers could leave letters or photos for their children, but Laird’s was empty. That night in their hotel room, Laird and his father called all the Ellises in the San Antonio telephone book, without success.

“I just didn’t want it to be a negative experience for me, if I upset the apple cart by showing up so many years later.”

They drove back home, and upon further reflection, Laird stopped his search. “I decided to leave it be [because] my biological mother hadn’t left anything for me to read or pictures,” he explains. “I felt like I could open myself to disappointment if I found her, and she didn’t want me to. I just didn’t want it to be a negative experience for me, if I upset the apple cart by showing up so many years later.”

Thirty years passed before Laird opened the search again, and this time it was his father who took the first initiative. For his son’s 52nd birthday, he purchased DNA tests. “He’s the one who did all the research, not me,” Laird explains. “I think he knew I had always been interested, especially in any siblings I might have had, as I pretty much guessed my biological parents would have passed away.”

To improve the odds of finding close genetic matches, Laird tested with multiple DNA companies. At AncestryDNA, he hit the genetic jackpot: a half-sister named Patrice, who went by Pat. Pat was looking for him. She’d learned of his existence after confessing to Charlotte that she had gotten pregnant as a teenager and given the baby up for adoption. “Well, don’t feel bad,” her mother had responded. “I did the same thing.”

Laird talked to Pat on the phone several times. She told him about Charlotte, who passed away some time ago. “My biological mother apparently wasn’t a very warm person,” Laird says. “She made sure her kids were fed and clothed, but she was not very loving.” He learned about his two older half-brothers, both of whom had also died. Laird made airline reservations to visit Pat last year. She wasn’t in good health and died before he could travel to see her.

Laird was heartbroken at not getting to meet his only known birth relative. But he made the trip anyway, talked to Pat’s roommates, and took home pictures of her.

Meanwhile, DNA matches at both Family Tree DNA and AncestryDNA seemed to pertain to Laird’s birth dad, John Hall. Laird corresponded with a fairly close match whose grandmother’s first cousin was a John Hall from Colorado. John rode the rodeo circuit (in places like San Antonio, Texas!) and was of the right age to have fathered Laird.

Unfortunately, John died in 2011.

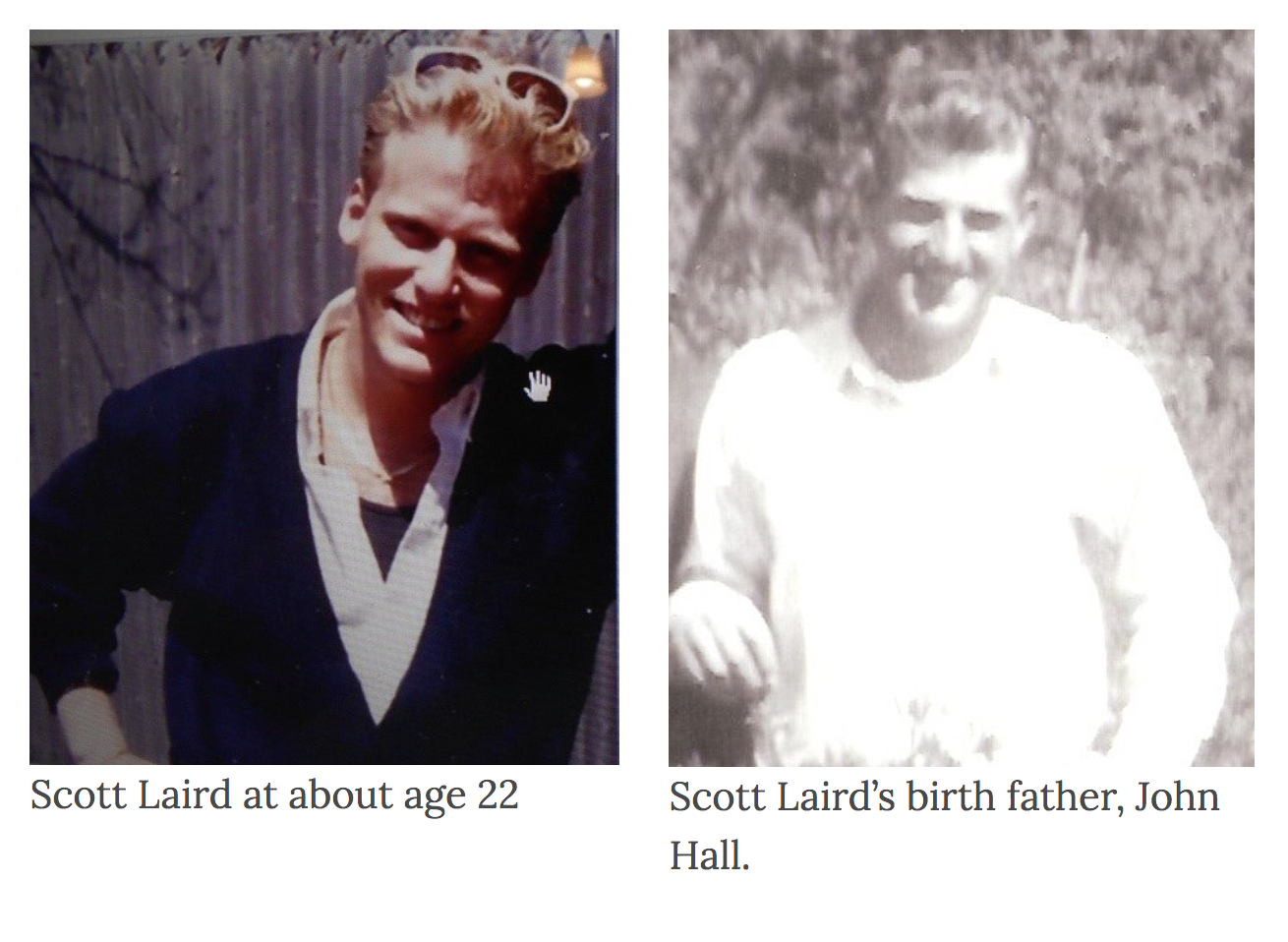

Laird’s matches put him in touch with his cousin Don, who had taken care of John in his last years. “My birth dad never knew about me at all,” Laird says. “But everyone I talked to said he was a warm, funny, feisty kind of guy. They sent me pictures of him. I look like him. In one picture taken at about the same angle we look almost identical.”

When John’s sister died, Laird was invited to the funeral—he’d missed the chance to meet yet another close birth relative (and his last living aunt) in person. “But it was a good opportunity to meet people on the Hall side,” he says. He and his wife drove 24 hours each direction for a one-day stay. “Everyone was warm and receptive. Now I’m friends with about 10 of them, and we’ve gotten to know each other more through Facebook.” As a result, he feels more connected to them and accepted by them.

There are things that are hard. “I regret not meeting my birth father,” he says. “I wish I had. I was so close: he didn’t die until just a few years ago.”

Now knowing more about his biological father, Laird can attribute some of his traits to him. “I love animals, just like my birth father,” he says. “He had his own horse and was kind of a horse whisperer: he could train them to do almost anything.”

But Laird is also acutely aware of all the traits and love he got from his adoptive parents. Of his two fathers, he says simply, “I feel really proud to be the son of both men.”

The post Adoptee finds birth roots after 30-year pause, with DNA and determination appeared first on MemoryWell.