The South Stockton classroom where Ashley Pearl Pana spent recess trapped indoors is still there, 16 years later.

When the wind stirred up dust and soot, when the sun stewed smokestack and tailpipe exhaust into smog, when pollution squeezed her airways, Pana’s asthma forced her inside, behind the classroom’s closed door.

“All the kids were playing outside, and I’d just watch them through the windows,” Pana, now 23, said while visiting her old elementary school. A new generation of children, masked against COVID-19’s newest threats to still-developing lungs, ran in the playground.

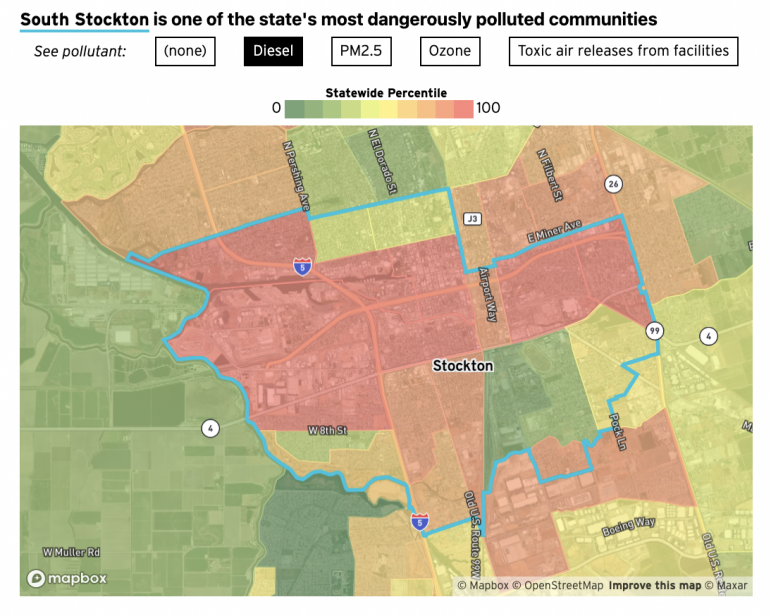

It was a clear day, the kind that makes South Stockton’s consistently filthy air difficult to imagine. But in one of California’s most dangerously polluted communities, emergency room visits for asthma attacks are among the highest in the state.

“No matter what, air quality is always an issue in my life,” Pana said. “Something I have to be constantly aware about.”

A four-year-old state law, known as AB 617, is supposed to clear the air for low-income communities of color that bear the brunt of California’s air pollution. The law established the Community Air Protection Program, which tasks residents and local officials with shaping regulations and steering state money to a handful of hotspots.

Hailed as “unprecedented,” the law was supposed to create a “groundbreaking program to measure and combat air pollution at the neighborhood level.”

So far, more than $1 billion in state funds has been appropriated for community grants, industry incentives and government costs. But it remains impossible to say yet whether the program has improved the smoggy and toxic air that almost 4 million people breathe in 15 communities.

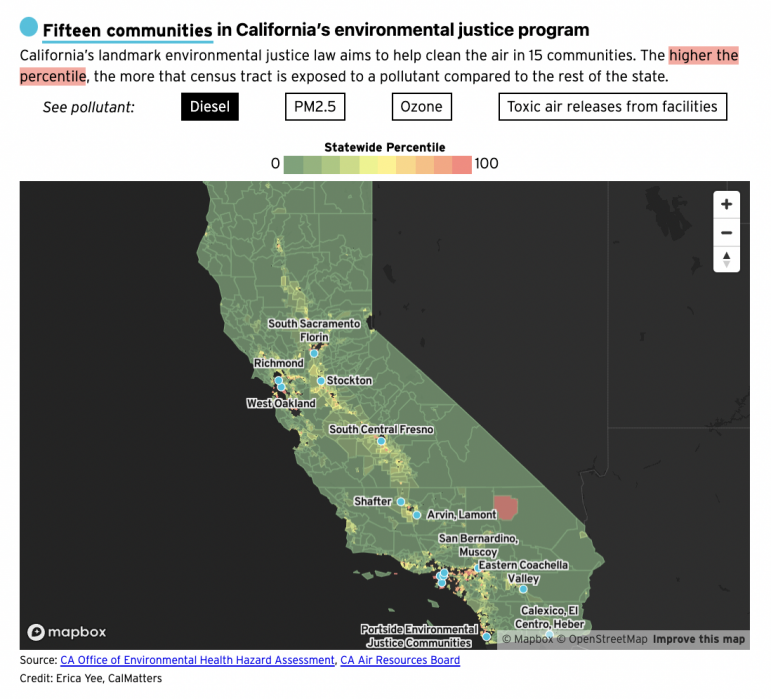

The 15 communities, stretching from the Central Valley to the border with Mexico, include Richmond, West Oakland, Stockton, San Bernardino and Wilmington. Predominantly home to Latino, Black and Asian American residents, many have high poverty rates.

Now, even as the law’s clean-air program prepares to fold in new neighborhoods, a major question lingers: Is it working?

“The jury’s out,” said Jonathan London, an associate professor of human ecology at the University of California, Davis who is studying the environmental justice law. It’s “an ongoing experiment with the potential for significant benefits, but also significant obstacles.”

Ashley Pearl in McKinley Park, where she played as a child while growing up in Stockton, on Oct. 13, 2021.

Pana shows the inhalers and other medication she uses daily to manage her asthma.

Environmental justice advocates have called the law toothless, and warn that it has “largely failed to produce the promised quantifiable, permanent, and enforceable emissions reductions.”

The struggle to achieve the law’s ambitious goals has been marked by battles between residents and local air regulators, and by jurisdictional juggling among agencies, each responsible for a different portion of pollution. Meanwhile, people continue to suffer.

“Is it having the improvements that I want it to have, at the level that I wanted to have? No, we need a lot more,” said Assemblymember Cristina Garcia, a Democrat from Bell Gardens who authored the bill that became law. “Is it engaging the community and empowering them, so they could push for change? … Oh, definitely.”

The law is just one tool — and, its author acknowledges, an imperfect one at that — intending to fix decades of environmental racism, land use decisions and freeway construction that have left poor communities of color hemmed in by California’s industrial corridors. It’s a monumental task, and experts say no one law will be victorious.

At stake is the health of millions of people who live near California’s refineries, ports, freeways and other sources of tiny, lung-damaging particles, gases that form smog and trigger asthma attacks, and toxic air pollutants linked to cancer.

UC Berkeley researchers lauded the program as a potential model for environmental justice policy, though they said it was too early to gauge its success. California Air Resources Board staff called it “a catalyst to change the way we work with communities.”

Yet Stockton residents and community groups have had a far different experience, tangling with local air regulators about funding decisions and delayed air pollution monitoring.

“At the beginning of this process, we were all Kumbaya,” said Dillon Delvo, co-founder of Little Manila Rising, a historic preservation organization turned environmental justice group in South Stockton.

“By the end,” he said, “it was terrible.”

“Tremendous amount of frustration”

For longer than half a century, California’s state and local air regulators have enacted pioneering rules to clean up pollution from smokestacks and tailpipes. Trailblazing mandates to tackle diesel exhaust — a known carcinogen — and other toxic air contaminants cut Californians’ cancer risk from breathing air by 76%.

But it hasn’t been enough. Parts of California still have the worst air quality in the country, with about 87% of Californians living in areas that exceeded federal healthy air standards in 2020.

In the San Joaquin Valley alone, breathing fine particles is estimated to cause 1,200 premature deaths from respiratory and heart disease per year. Poor communities of color are still exposed to double the cancer-causing diesel exhaust than more affluent neighbors.

Garcia’s law aimed to tackle pollution hotspots by injecting a greater role for community activists and residents into a complex regulatory process. Local air districts responsible for regulating smokestack pollution must now work with communities to craft clean air plans. The law also calls for increased air monitoring, bigger fines for polluters and faster deployment of new pollution-scrubbing retrofits on smokestacks.

Deldi Reyes, director of the Air Resources Board’s Office of Community Air Protection, told board members at an October meeting that there’s been progress since the environmental justice law was enacted.

An estimated 75 tons of fine particles are expected to be cut across 11 communities after five years of implementation, equivalent to removing 75,000 heavy-duty diesel trucks from California roads, Reyes said. About 22% of these improvements are because of statewide rather than community-specific efforts under the new law, air board staff reported.

But neither the law nor the state-developed guidelines for its implementation include specific targets for measurably improving air quality or public health in the selected communities.

Though the program relies heavily on community time and effort, it leaves decisionmaking where it has always rested: with state and local air regulators.

“I’d like to see more accountability built into the program,” said Dr. John Balmes, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and a member of the California Air Resource Board. “I don’t think that’s too much to ask.”

The air board’s Reyes urged patience. Of the 15 communities, three are still developing their clean-air plans and four are in their first year of implementation. “It’s just too early to point to any of the communities and say, ‘Oh, they haven’t met their goals,’” she said. “Air quality does not change on a dime.”

An environmental justice advocate in Oakland, Margaret Gordon, agreed. “This is not instant. This is not Top Ramen.”

Even the law’s birth was contentious.

The legislation was framed as a companion to a bill extending the life of cap and trade, California’s landmark carbon market designed to reduce climate-warming emissions. Under cap and trade, companies operating refineries, power plants and other industrial facilities can buy or trade credits to meet a declining cap on greenhouse gases, without cutting local pollution.

Environmental justice advocates fought the cap and trade extension, declaring it a “deal with the devil” that usurped local power to cut carbon emissions from industrial facilities like refineries. One analysis found that neighborhoods with increasing pollution during cap and trade’s early years were more likely home to people of color and people living in poverty.

The new law — less stringent than an earlier version that died in the Assembly — was supposed to end the unequal pollution burden.

Yet many residents and environmental justice advocates say the law pits disadvantaged communities against each other for selection in the program, and its effectiveness varies drastically from air district to air district. In a UC Davis assessment, participants described a program that fails to provide adequate training for community members who may have language barriers and limited knowledge of topics like refinery flares and pollution controls for ships.

“This was like a beautiful thing that was going to bring us something into our communities to protect them from cap and trade, and also try to get the community involved,” said Magali Sanchez-Hall, a Wilmington resident and environmental activist. “That’s not what I have experienced, at all.”

The oil industry, a major source of industrial air pollution, has said it supports the intent of the environmental justice law. But at the negotiating table with legislators, it pushed back against stricter controls over pollution and later tried, but failed, to remove language in state guidelines that called for the “most stringent approaches for reducing emissions.”

Air district boards must balance environmental improvements with the economic impact of their rules, which can each cost billions of dollars. Oil companies and other industries often seek longer deadlines to soften the economic blow and have time to perfect new technology.

State and local air regulators list frustrations of their own in implementing the law: insufficient funding, inadequate time to repair community relationships damaged over decades and no new authority over local governments’ land-use decisions, such as warehouse construction.

“There is a tremendous amount of frustration between the various community groups and the district,” said Wayne Nastri, executive officer of the South Coast Air Quality Management District, the powerful agency responsible for cleaning the air of 17 million people in the Los Angeles basin. “It’s difficult to put those programs together when there isn’t trust between the community groups and the regulators.”

Asthma, freeways and port pollution in Stockton

On the banks of the San Joaquin River sits Stockton, home to an inland port that lends its name to the city’s Minor League Baseball team, the Stockton Ports. Trucks roar over freeways that cleave a city spotted with heavy industry, creased by rail lines and ringed by farm fields.

Vehicles are a major source of smog and fine particles in South Stockton, with activities related to the port accounting for about a quarter of the area’s dangerous diesel exhaust. Two of the 18 Stockton census tracts included in the state program are ranked in the top 1% of the most pollution-burdened in California. Eleven are in the top 25%.

Among the most racially diverse cities in the country, Stockton bears the scars of racial residential segregation and redlining. State and local officials plowed the Crosstown Freeway through communities of color, with demolitions and displacements starting in the late 1960s.

Among the neighborhoods crushed beneath freeway expansion was Little Manila, where only two of the original buildings in a once-vibrant Filipino American community remain.

Historian and author Dawn Bohulano Mabalon wrote about watching one of Little Manila’s last blocks destroyed in 1999. In its place now stands a gas station and a McDonald’s. Mabalon, who developed asthma growing up in Stockton, died three years ago from an asthma attack while vacationing in Hawaii, at age 45.

Stockton neighborhoods, especially those near the freeways, have some of the highest rates of emergency room visits for asthma in California.

Dillon Delvo, a second-generation Filipino American who co-founded Little Manila Rising with Mabalon to battle for preservation of the community, is now fighting for clean air, too.

“It would be irresponsible for us to try to save these buildings and expect people to come here, when this,” Delvo gestured at the freeway looming over him, his voice raised over the roaring trucks, “exists right here. And the fact is that there are families in this community that need to breathe this air.”

For Pana, the consequences of a childhood spent in South Stockton still linger. Her family moved there from the Philippines when she was 2 years old. But she didn’t realize just how dirty the air was until she moved to Stockton’s far whiter Northside with its far cleaner air.

Pana said she has been treated in the emergency room twice in the past year alone for asthma attacks, and she now uses inhalers and other medications daily to keep her airways open.

“That’s just my life, and it was normalized,” said Pana, an aspiring social worker and former youth climate advocate with Little Manila Rising. Now, she knows: “It’s not normal.”

Joining the Community Air Protection Program, however, hasn’t been the salve for generations of environmental racism that Pana, Delvo and others had hoped for.

Delvo once sat on the program’s community steering committee before a colleague took over the role. Now he wonders whether the law can ever really be effective, given its reliance on air districts like the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District that have long presided over some of the most polluted air in the country. At a board meeting, a top air district official called the committee merely a “consultative body” without “any direct authority.”

“I think the intention of the legislation is good,” Delvo said. “But once it comes into the hands of whatever local agency is controlling it, they control the outcome of it. That’s the problem. That’s why you have widespread marginalization, specifically in the Central Valley.”

District officials applauded community members for “improving the lives of their families, friends and neighbors” and helping secure $32 million in government investments for cleaning the air in Stockton. But the air district’s Jessica Olsen, director of community strategies and resources, acknowledged that the “nitty gritty” of crafting pollution measures may have eclipsed efforts to build the community’s trust, “maybe right when it was most critical.”

The effort in Stockton has been plagued by delays and jurisdictional infighting. One example: A program to monitor the air at local schools that stalled after the Stockton Unified School District refused to host the devices, according to the air district. Stockton Unified representatives did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The biggest battle came when advocacy groups questioned a district program to provide $5 million to the port to help pay for cleaner equipment, tugboat engines and a pollution capture device for tankers.

“If this is just a process where we’re handing out money to industry to subsidize expanding their emissions, then that’s not something that (we) can be in support of,” Catherine Garoupa White, executive director of the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition, said at a community steering committee meeting.

Ultimately, state and local regulators approved a plan that eliminated the port incentives, but did not reallocate the $5 million to another Stockton program.

Home to fertilizer importers, petroleum and biodiesel storage, cement companies, a biomass burning facility and other industries, the port supports thousands of jobs. Another 400 acres are approved for new development. Some of its tenants are planning expansions, too.

Two years ago, state air regulators told the port that one tenant’s plans to upgrade “would increase exposure to air pollution in disadvantaged communities.”

But Jeff Wingfield, the port’s director of environmental and public affairs, said port expansion and pollution don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand. About 60% of the port’s cargo-handling equipment is zero emission, he said. Cleaning up operations is costly, so extra funding would help. “Our annual budget is like $50 million. That’s a significant risk, and a significant investment for us,” he said.

The port has pledged to continue working with the community on its own clean air plan. And the air district’s Olsen said her team is working to restore the relationship with community groups, “learning those lessons, knowing we need to build that trust back up.”

“It’s kind of been a roller coaster,” Olsen said.

A decades-long battle in LA County’s port communities

About 350 miles south, in the southwestern end of Los Angeles County, Wilmington, Carson and West Long Beach joined the Community Air Protection Program a year ahead of Stockton.

District officials say two sets of important emission-cutting rules enacted last year were accelerated because of the environmental justice law.

People in the region, which is predominantly Latino, live with polluting industries almost in their backyards: five oil refineries, nine railyards, the nation’s two busiest ports, 43 miles of freeways, three Superfund hazardous waste sites and other industrial facilities. Refineries there already must meet some of the nation’s strictest rules, yet oil production and refining are still the largest sources of industrial pollution in the communities.

Residents in the Los Angeles/Long Beach port area visit emergency rooms for asthma attacks 40% more often than the state average. And their cancer risk from toxic air, primarily from diesel exhaust, was 35% higher than the Los Angeles basin’s average in 2018 — although it’s less than half the estimates for 2012 and 2013.

After months of discussions with community activists, the air district committed to cut smog-forming gases and sulfur from oil refineries in half by 2030. In a big step toward that goal in November, the South Coast air district set new mandates to eliminate up to eight tons a day of emissions from 16 oil refineries and other industrial plants.

The new rules, projected to cost the companies more than $2 billion, are intended to satisfy the environmental justice law’s requirement that industries accelerate installation of the best available technology to control smog-forming emissions and other pollution. They also play a key role in the Los Angeles basin’s latest efforts to comply with national health standards for smog — a half-century-long quest for the nation’s smoggiest region.

In their negotiations, oil companies asked the district to prove “both technical feasibility and cost effectiveness” and “provide a reasonable schedule” to install new technology on refinery heaters. “The District has no way to know whether these products will achieve commercial readiness within 10 years, or ever,” the Western States Petroleum Association wrote in August.

As a result, the timelines stretch to 2035 — far beyond the law’s Dec. 31, 2023, deadline. About half of the emissions reductions are expected by next year. The tradeoff for getting the big cuts in smog-forming nitrogen oxides was to give industry more time and flexibility, said Susan Nakamura, the South Coast air district’s assistant deputy executive officer.

Another measure adopted last year takes aim at diesel exhaust and smog-forming gases from Southern California’s warehouses, a growing source in the San Bernardino area, which is another of the 15 communities in the state’s environmental justice program.

The Bay Area also enacted a rule last year to cut refinery pollution. Combined, the measures stand out because the environmental justice program has been criticized for relying more heavily on industry incentives than mandates.

But in the Wilmington, Carson and West Long Beach area, advocates called the new refinery rule a limited victory that has taken, and will take, far too long.

Now all eyes have turned to pollution from the ports, where shipping backups have caused soot and smog to skyrocket recently. After years of negotiations with the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the air district board decided that if the ports don’t come up with an acceptable clean-air plan by this Friday, it will order the staff to draft mandatory rules.

“It’s still a battle to get clean-air regulation,” said Chris Chavez, who grew up in West Long Beach and is now deputy policy director with the Coalition for Clean Air. “It’s just that we have a better shot at it now than we had a couple years ago.”

Community groups call for change

After more than four years, the law has reached an inflection point.

The People’s Blueprint, proposed by community groups and environmental advocates, seeks explicit new policies and training promoting equity and inclusion. It also calls for greater transparency and community control over budgets, and consequences for air districts that fail to show progress or act without community agreement.

State air board officials are reviewing the proposal, and plan to draw from it to draft new guidelines expected to come before the board next year. “There is nothing off the table,” the air board’s Reyes told CalMatters. “We really need to find ways to expand the benefits of the program … because it’s not sustainable, especially if the funding levels stay consistent in the way that they have.”

Millions of Californians live in thousands of census tracts the state considers disadvantaged, in part because they may bear disproportionate burdens of pollution. Focusing on only 15 communities, Garcia said, “is not satisfying. We’re leaving behind a bunch of potential communities, and they all deserve justice.”

Legislative efforts to tackle environmental justice more widely, however, have stalled.

Last year, Garcia introduced a bill barring refineries and other facilities that fail to promptly install the latest pollution-scrubbing technology from participating in cap and trade. Bills in the Senate and Assembly proposed adding environmental justice representatives to the Los Angeles basin air district’s board. Two more bills tried to take aim at industrial and warehouse expansion.

None succeeded, though some have already been revived for another pass through the Legislature.

In the meantime, residents across the state are still waiting to find out whether California’s landmark environmental justice law will make a difference in their daily lives.

If not, “then community members and organizations have to take matters into their own hands,” Pana said, standing outside her old school in Stockton. “We’re going to keep fighting for it.”