What’s it like campaigning for re-election in 2022 when you’re not sure which voters will be in your district?

Just ask U.S. Rep John Garamendi, a Democrat who lives in Walnut Grove and now represents voters in a district that stretches from Fairfield and Davis to Yuba City, as well as part of the Mendocino National Forest.

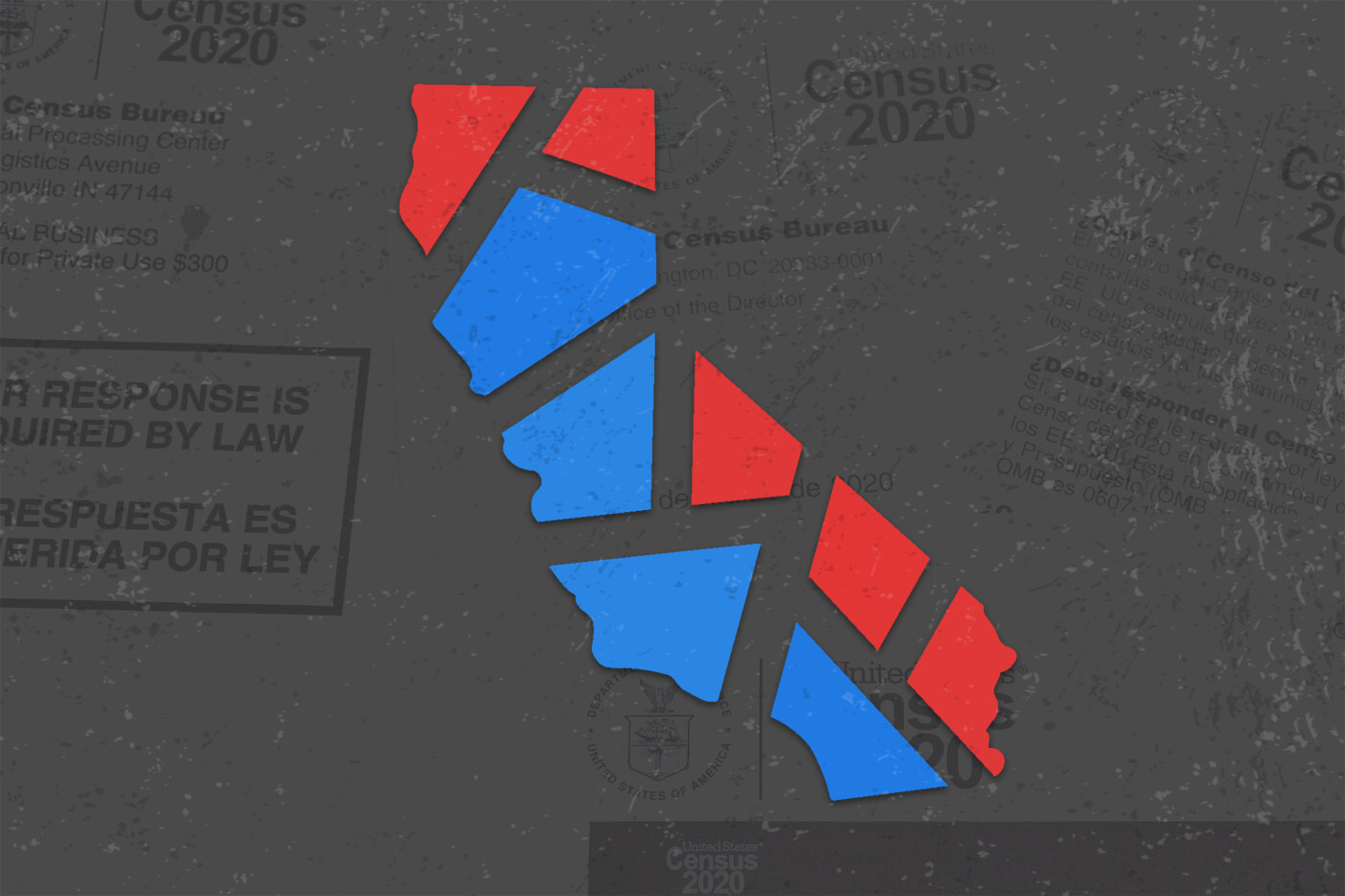

Under draft maps from California’s independent redistricting commission, his current district has been chopped up, with significant portions shifted to majority Republican districts now represented by Doug LaMalfa and Tom McClintock and to a district held by Democrat Mike Thompson.

On top of that change, Garamendi would be stuck in the same district where Democratic Reps. Ami Bera of Elk Grove and Doris Matsui of Sacramento also live, though he could try to run in a neighboring district that doesn’t have an incumbent.

“For every California representative, there’s a high degree of uncertainty,” Garamendi told CalMatters by phone from Washington, D.C. “It appears as though the commission is developing an Interstate 80 district. Exactly where it begins and where it ends is unknown. But I’ve represented the Interstate 80 corridor for 11 years, and I’m looking forward to doing it again.”

Garamendi isn’t the only one facing uncertainty.

The redistricting commission, which last week approved its first official draft maps, isn’t supposed to consider the fate of current elected officials in drawing new districts — or even know where they live.

But as it enters its next phase of work with two weeks of public input meetings that started Wednesday, the political ripple effects for some incumbents are difficult to ignore.

After the public hearings, the commission plans 14 line-drawing sessions to refine the preliminary maps before voting in late December on final districts that will be used for the next decade, starting in 2022.

But as it stands now, a sizable number of House members and state legislators have been placed in less politically friendly districts, or in the same district as another incumbent.

While the numbers vary in early analyses, a study out Tuesday from the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California says 20 members of Congress, 29 state Assembly members and 14 state senators have been drawn into a district with another incumbent.

How much consideration is given by the commission whether incumbents are put in the same district?

Zero, said commissioner Sara Sadhwani.

“It’s really not something that we look at or contemplate. Our constitutional mandate is clear,” she told CalMatters. “Instead, we focus on the people and on Californians and what kind of things tie their communities together, what kind of representation they want to see.”

Legislative musical chairs

Legislators whose political careers may be at stake, however, are definitely looking. The commission is set to hear public comment today on the draft Assembly districts and Friday on the state Senate ones.

For example, due to slower population growth in Los Angeles County, the draft state Assembly map breaks up Democrat Miguel Santiago’s Latino-majority district and redistributes areas to neighboring districts. Santiago’s own residence would be in Assemblymember Wendy Carillo’s district, according to California Target Book, a political data firm.

Also, Republican Assemblymember Kelly Seyarto of Murrieta remains in his district, but most of his voters are shifted to another Republican district in Riverside County. And the preliminary state Senate maps put Anna Caballero and fellow Democrat Melissa Hurtado in the same Central Valley district.

In previous redistricting cycles, some legislators who may have been drawn out of their districts chose to retire, or were forced to step aside due to term limits. In the first election after the 2011 redistricting, more than 30 Assembly members were barred by term limits from running again, according to Redistricting Partners.

But this time, only four senators are termed out before the 2022 election, and no Assembly members are, according to redistricting expert Paul Mitchell. That means there could be stiff competition in many of the new districts, starting with the June primaries.

“It does create kind of a frenetic, potentially very expensive, potentially very nasty, quick primary that would happen pretty quickly after the passage of lines,” Mitchell said.

There is one upside this year for incumbents who have been put in a new district, though. While state legislators are legally required to live in their districts, lawmakers added some loopholes in 2018 by passing a law that declared that where they are registered to vote will be considered their home and that made it more difficult to prosecute them for misstating their true place of residence.

Then there’s what may be the most confusing factor in redistricting — the staggered four-year terms for state senators. Because only half the state Senate is elected every two years, the commission will try to make sure that in numbering the new districts, as many voters as possible stay on the four-year election cycle and as few voters as possible have to wait six years until their next chance to elect a senator.

But it’s still possible that some voters will have two senators, or none, living in their new districts between 2022 — when the 20 even-numbered districts will be on the ballot — and 2024, when the 20 odd-numbered districts are up, according to Tony Quinn of California Target Book.

It’s also possible that some legislators will be directly affected, though incumbents now headed to the ballot in 2022 can’t extend their terms just by being placed in a district with a 2024 election date. (Legislators represent the districts to which they are elected, even if the lines change before their term in office ends.)

Congressional outlook

For the first time ever, California is losing one of its congressional seats due to slower population growth than other states. In this once-a-decade redistricting, that could force some incumbents to scramble.

While members of Congress don’t have to live in the districts they represent, it can be used by their opponents against them if they don’t.

If the draft maps stay as is, other Democrats who would also see their districts drastically change include first-term Rep. Sara Jacobs in San Diego County and Lucille Roybal-Allard of Los Angeles County, who was first elected to Congress in 1992, according to an analysis from California Target Book.

The preliminary districts would also mean more competitive races for others. Central Valley GOP Rep. Devin Nunes would see his district shift from majority Republican to majority Democratic, according to the California Target Book analysis, but he could run in a friendlier district. Mike Garcia, the only Republican representing Los Angeles County in Congress, would also be in a bluer district.

Republican Rep. Darrell Issa, whose San Diego County district would become more competitive under the preliminary maps, urged supporters in a tweet today to contact the commission about keeping Fallbrook in his district.

Democrat Joseph Rocha, who is running against Issa, said that while the maps can be “a little bit of a roller coaster,” the drafts are currently favorable to his campaign. “It’s sort of a bit of a perfect storm that we are seeing ourselves navigate very well,” Rocha said in an interview with CalMatters.

On the Democratic side, Reps. Josh Harder of Modesto, Katie Porter of Irvine and Mike Levin of San Diego would see their districts change to majority Republican districts.

Porter said that while she came to Orange County to live and work in Irvine, she was aware when she ran for the seat in 2018 that the county’s population was growing and that redistricting was around the corner.

“I represent Orange County families,” Porter told the Sacramento Press Club last week. “They want a government that works for them. They want a government that is protecting their environment, they want a government that’s delivering tax fairness. I think those kinds of issues and the way that I focused on representing this area serves me well in representing different communities in Orange County and even thinking about the state’s interest as a whole.

“We’ll see what happens.”

Some members of Congress aren’t waiting. They’re stepping aside voluntarily — and adding to the potential sweeping change to the California delegation, while also possibly opening up seats for legislators seeking higher office.

Rep. Jackie Speier, a Democrat who has served in the House since 2009, announced Tuesday she won’t seek re-election next year. The draft maps don’t significantly change her district, which covers most of San Mateo County and the southwest quarter of San Francisco. It overlaps with the districts of state Sen. Josh Becker and Assemblymember Kevin Mullin, Democrats who could be candidates to succeed her.

Now, Democrats hold 42 of the 53 House seats in California, Under the preliminary districts, 40 of the 52, including Garamendi’s new district, would likely elect a Democrat, based on election results over the past decade, according to the PPIC analysis.

Nationally, however, Democrats face an uphill battle to keep their majority in Congress in the 2022 midterm elections, partly due to Republican-controlled redistricting in other states.

Advantages of incumbency

Voters tend to favor incumbents, a 2012 Harvard University report on the impacts of redistricting found.

“Many fewer incumbents retire today than in previous generations; reelection rates of those who do run for reelection exceed 90 percent. As a result, turnover in U.S. legislatures is extremely low and the tenure of the typical legislator grows longer,” according to the report.

And letting elected officials draw their own districts is a big reason. California voters decided in 2008 to take that power away from the Legislature.

“I think a part of why Californians adopted this independent commission process was to change the rules of the game,” Sadhwani said. “For so long and in so many states, and this certainly is true still in many states, lines are drawn by the incumbents themselves, by sitting legislators, and are done so in a way that is to their advantage.”

Sadhwani also addressed the fact that some voters like their representatives and don’t want them to change.

“To the extent that most communities want to identify themselves as a community of interest, that’s perfectly valid and something we take into consideration. We cannot keep every community of interest together,” she said. “We are trying our best and trying to balance as much of the testimony as we possibly can.”

As for Garamendi, who was first elected to Congress in 2008, he’s seen his district shift before, and is preparing for what this round of redistricting will bring.

“I told people, back in 2010, 2011 when my district moved northward from Contra Costa County that they may not vote for me, but I would continue to represent them, and I’ve done that here in Congress. So whatever the final lines are and whether a particular community is in or out, I don’t know,” he said. “I’m going to continue to work on the issues that I worked on all my career.”