For many performing artists across the Bay Area and the world at large, the forcible closing of venues for music, theater and dance in March 2020 was a harrowing experience most have still not fully recovered from. But there was a new opportunity in this time away from the stage — to look inward. As previously reported by Bay City News Foundation and many other local, regional and national outlets, just about every facet of the arts world took a long hard look at itself during the COVID-19 pandemic, and what it saw wasn’t pretty.

A milieu of intersecting devastations to art and equity, like racism, classism, sexism and xenophobia, have long permeated not only artistic spaces and communities, but also the hearts and minds of artists themselves. Evidence of these inequities manifests distinctly depending on the medium, where written and visual forms can be documents in and of themselves, and the theater arts, both in stage and in film, have written components and visual recordings to look back on. In short, there is language to chronicle change over time, and language to discuss what the audiences and critics see, or don’t.

Also, it’s made clear by who wins awards at the Oscars, the Emmys and the Tonys — let alone who gets nominations — where the industry stands. Last year, the Bay Area’s theater community took a page from the work of more than 300 theater artists across the United States, celebrities included, who had contributed to an open letter addressing the structural gatekeepers of white American theater.

The Bay Area’s “The Living Document” began as a Google doc to air grievances with local theater companies, their leaders and their critics. In just a year, it’s become a platform with original data, action plans and a pulsating network of artists from around the Bay Area and beyond to keep the document and the demand for progress alive.

It gets a little more complicated when it comes to dance. It’s easy to see, in programs and under the stage lights, who is getting top billing, but analysis is harder to come by. How can dancers, their choreographers and their disciples point to what is wrong when there is so little language to give these problems and their solutions names? Esteemed dancer, choreographer, curator and Bridge Project founder Hope Mohr has a few ideas, and a new book in which to distill them.

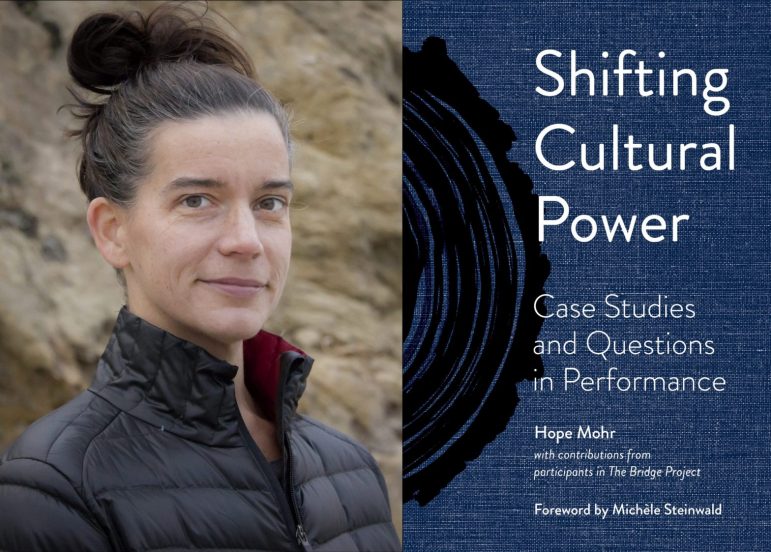

“Shifting Cultural Power: Case Studies and Questions in Performance,” published Sept. 1 by the University of Akron Press, is part personal archive, part scholarship and wholly rooted in demanding more from the dance world when it comes to centering the works of non-white, non-cis and non-straight dancers, choreographers and artists.

Mohr, a San Francisco native trained in New York before returning to the Bay Area, was approached by the National Center for Choreography at the University of Akron in Ohio to write the book back in 2018, in anticipation of the 10-year anniversary of her performance platform, the Bridge Project, in 2020.

The project began in 2010 as an equity effort within Mohr’s dance company to include talent and themes the members of the company, who were mostly white at that time, couldn’t provide, and it has evolved into a canopy for intersectional performance art that seeks to address the disparities in our society, demonstrated in the many art forms where they manifest.

“Shifting Cultural Power” seemed like a straightforward narrative at first, but as Mohr began researching and drawing from the decade of archived performances, guest collaborators and interviews from the Bridge Project — nevermind the impending pandemic — it became clear the book had a lot more to say.

“There are some books about curatorial activism in the visual arts, and a lot of literature about social practice in the visual arts. But in the performing arts, not so much,” Mohr says. “I thought that writing the book was a good opportunity to really talk about what it means to present art that is at the intersection of social justice and culture.

“[The book] started out as a way of archiving [my] curatorial work in the performing arts,” she continues, “but through that process of writing, I started to see certain themes arise. I wanted to really surface the lessons about, as a white person, what it means to make space for other voices and the arts.”

Mohr has previously been part of the NCCAkron’s Low-Residency Dance Writing Lab, a project spearheaded by the center’s artistic director Christy Bolingbroke, who had previously worked with Mohr at San Francisco’s ODC Theater, to gather some of the dance world’s thought leaders and help cultivate clearer language about what dance is, what it provides a community and how intentional inequities are upheld and obstructed from change.

Bolingbroke writes in the opening pages of Mohr’s book that the lab, and the efforts born of it, provides an opportunity to answer the question “How can we invest in and augment other aspects of the field [of dance] at large?” “Shifting Cultural Power” is one attempt.

Mohr, a white woman, identified with feminism early on in her dance career. She founded Hope Mohr Dance in 2008, and the Bridge Project in 2010 to broaden the scope and diversity of HMD and its audience, which she realized was mostly white. It was also evident in the years following the 2008 recession that equity was not a priority in most dance spaces, or at least a visible, vocal one.

The book draws on Mohr’s personal journey decolonizing her own company, which included reshaping leadership to a more egalitarian, communal process and redistributing financial compensation. Mohr makes a point early on that this is a book mostly for white people like herself, to recognize the impact of their presence in dance and artistic spaces and work against it.

In addition to Mohr’s own story, she interpolates the voices and writings of numerous thought leaders across artistic disciplines she has known and even worked alongside, including gender theorist and UC Berkeley literature professor Judith Butler, UC Santa Cruz dance professor Gerald Casel and UC Berkeley philosophy professor Alva Noë, in chapters that discuss how to recognize and actively work against the self-interest of whiteness.

“With social justice and racial equity as the underlying values within my current curatorial approaches, I know that someday soon, if I am true to my morals, I will be curating myself out of the room,” Mohr writes.

She calls the book a tool, an instrument to facilitate the uncomfortable, necessary conversations these toxic, stifling dynamics have over artists, their institutions and the audiences who patronize them.

There are numerous case studies and annotations about the Bridge Project’s own journey to restructure and reconceive of itself as an artistic community actively working to achieve equitable leadership, and not just produce equitable art. The project now comprises four distinct endeavors, the Community Engagement Residency, the Multidisciplinary Performance Series, the Teaching Artist Series and the Public Dialogue Series. There are prompts and collective exercises toward the end of the book that can be facilitated in-studio and an archive full of notes for those who feel lost taking on such an ingrained challenge.

“It is a call for change,” Mohr says. “It’s not just for administrators or educators, it’s also for artists, because you know it’s so important not to silo political commitments to the intellectual or organizational side of things. Art and politics are not a zero-sum game.”

In that vein, it’s one thing to write about change and another to see it through a performance made up of human beings. The Bridge Project began its transition to distributed leadership in early 2020, starting by redistributing pay and relinquishing decision power from the traditional role of directors.

Mohr says these choices inherently change the pace of producing a show, but soon the artists involved will be able to demonstrate the fruits of their labor to a live audience. Running Tuesday to Oct. 2, Hope Mohr Dance’s new show, guided by a horizontal decision-making structure and tackling gender and filicide, “Bacchae Before,” will premiere at the Joe Goode Annex in San Francisco, with nightly performances as well as a livestream of the Oct. 2 show. Opening night will be the company’s first live performance in nearly two years.

So in the meantime, the cast is hard at work, flexing muscles that haven’t had their spotlight since the virus started ravaging the country. As venues tentatively reopen to host audience members starved for art and performance, it still feels unclear to Mohr how far we’ve come, and what the pandemic and its reckoning will mean for the future of the art world, let alone dance.

“There’s no cookie-cutter recipe for change,” she says. “The whole art field has undergone a big racial reckoning over the past year. And so in some ways, the book is already out of date because it was finalized in the midst of this recognized reckoning. As folks are kind of rushing back into production mode, it’s so fruitful to put dancing [in] conversation with those perspectives, and I worry that some of the conversations about equity may be forgotten. Time will tell about the impact this year has had.”

“Bacchae Before,” a cross-disciplinary experimental work by choreographer Hope Mohr, playwright Maxe Crandall, puppeteer Mike Chin and performers Belinda He, Wiley Naman Strasser, Karla Quintero and Silk Worm, is inspired by Anne Carson’s irreverent translation of Euripides’ ancient Greek tragedy “The Bacchae” and modern-day gender reveal parties. It runs 8 p.m. Tuesday-Oct. 2 at Joe Goode Annex, 401 Alabama St., San Francisco. A livestream of the performance will also be available at 8 p.m. Oct. 2. Tickets, $15-$75, are available at https://joegoode.org/event/bacchae-before/.