Leaders from a newly formed revitalization task force joined California State Parks representatives last week in announcing a partnership to honor a piece of California Black history in the Central Valley.

Randall Cooper, chief executive officer of the Global Economic Impact Group, which will lead revitalization effort, said the once-prosperous community of Allensworth was devastated by a series of racist decisions and policies and never was able to recover.

“We have to create something to get people to want to come out here,” Cooper said.

More than a park revitalization, the work to restore Allensworth is to restore and honor Black history in California while bringing new tourism opportunities to the region.

Present at the event were also Mayor Bryan Osorio of Delano, Mayor Patricia Nolen of Corcoran, representatives from Gov. Gavin Newsom, the Kern County Black Chamber of Commerce, Mother’s Against Gang Violence, the African American Network of Kern County Buffalo Soldiers and representatives of the Allensworth State Historic Park Foundation.

Representatives of state Sen. Melissa Hurtado, U.S. Rep. David Valadao and Tulare County Supervisor Vander Poel presented certificates to commemorate the work.

Allentown: a town robbed of its potential

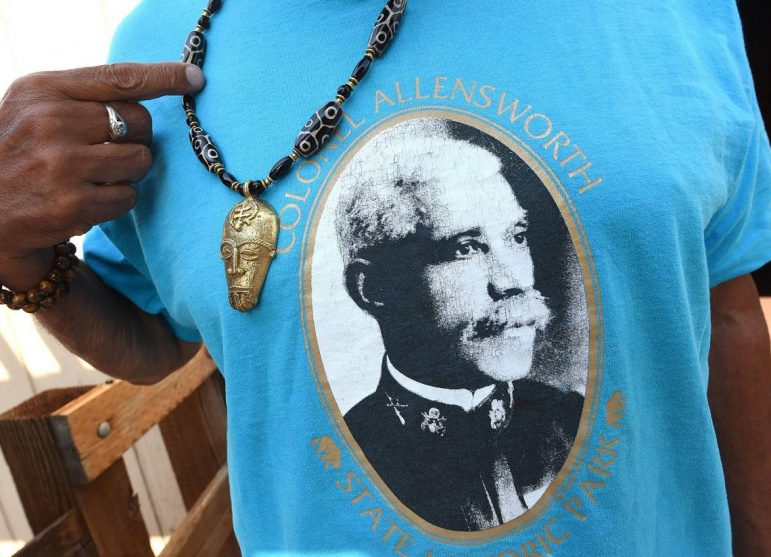

Named for its founder, the town of Allensworth was established in 1908. A former slave, a navy lieutenant colonel, an educator, a pastor, and a community leader, Lt. Col. Allen Allensworth had the vision to create a town where Black residents could prosper.

And at first, that’s what he did.

Allensworth had stores, a bakery, a school, a church that built a strong community. Allensworth enjoyed economic prosperity thanks in large part to its proximity to a train station. The community had over 300 residents at its peak and brought in thousands of dollars of business per month.

The town’s founding father had plans to bring a university and create the “Tuskeegee of the West.”

Then a series of tragedies thwarted the growth of the town. First was the untimely death of Col. Allensworth, whose leadership was crucial in the early years of the town’s development.

Then the town faced two devastating economic setbacks, both of which experts say had racist motives.

The first was the decision to move the train station to the nearby town of Alpaugh.

“They moved the train from the white train passengers didn’t want to keep coming here and deal with the African Americans,” said Cooper.

Water access was another hindrance to the town’s potential.

Cooper said white farmers dammed the river and diverted the water, leaving Allensworth’s Black farmers high and dry.

Eventually, the town’s residents started to move away. Today, there are about 500 residents in the area surrounding the park, made up primarily of Latino farmworkers and the Black descendants of Allensworth families.

Park supporters noted that Allensworth’s thriving community predates the African American community of the Greenwood neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Better known as the Black Wall Street, the affluent Black community was attacked and burned down by a racist mob in what is known today as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

“Most all the black towns they started up after the Civil War were either just burned down, destroyed, or crippled,” said Sasha Biscoe, president of the Friends of Allensworth Park nonprofit. “Allensworth was crippled.”

A vision for historical tourism in the valley

Community leaders said that they want to make sure the park’s history is uplifted and shared and that the park has a new presence in the Central Valley.

“They (the town founders) did this for us,” said Xenia King, Foundation Advisory Member and President of Mother’s Against Gang Violence. “I want to bring this to our generation.”

Biscoe said that the idea is to understand what it would have been like to live here in the early 1900s and to understand why they came here.

“You’ll hear about what happened here and how they lived, but they don’t talk a lot about why people came here,” said Biscoe. “What would it take to for you to uproot your family and come here? You were running for your life.”

Currently, the park hosts four annual events, which they plan to double.

Plans for the park include an expanded visitor center, an amphitheater for events, shade structures, an area for kids to play, and more parking space for tour buses and mobile homes.

Attendees at Wednesday’s event floated several ideas to revitalize the park.

C. Eziokwu Washington, vice president of Friends of Allensworth, said he wants to see more gospel, jazz, reggae, and other musical festivals. He said he would also like to see an interactive, historical experience like the colonial Williamsburg site in Virginia. Other attendees mentioned hosting the Black rodeo.

GEIG leaders say they hope to secure funding from county and state sources to revitalize the park.

“Look around. You can see how much the state parks have invested here,” said Cooper.

William Broomfield, GEIG’s chief operations officer, said they hope to create tourism and opportunity in the Central Valley.

Broomfield stressed the importance of local participation. He said he has been involved with numerous events at the Allensworth State Park in the past, but the park didn’t get much support from the city of Bakersfield.

“You can do all the improvements and everything else in the world, but if you don’t have that participation and that appreciation for this park that’s right here in your own backyard,” said Broomfield, “then you don’t have anything.

An opportunity for reparations

In June, a state committee to study the impact of slavery and systemic in California against African Americans started its two-year process. The committee will explore the possibility of reparations for California’s African American community.

There is still much debate around what constitutes a reparation and how it could work.

In the Southern California city of Manhattan Beach, the descendants of a Black family that once owned a property in the area could get some of the property back as a form of reparations.

Cooper said he thinks the funding for Allensworth Historical State Park should be part of that conversation on reparations.

“They took away their water, and they took away their income,” he said. “That demands reparations.”

Melissa Montalvo is a reporter with The Fresno Bee and a Report for America corps member. This article is part of The California Divide, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequity and economic survival in California.