Low-income Californians enrolled in Medi-Cal have been vaccinated at far lower rates than the overall population in all 58 counties, according to state data.

The disparity reveals a strong economic divide between the vaccinated and unvaccinated throughout California.

About 45% of Medi-Cal enrollees eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine (those 12 and older) had received at least one dose as of July 18, compared to about 70% of all eligible Californians, state officials said Thursday.

Nearly 14 million Californians are enrolled in Medi-Cal, the state’s health care program for low-income people.

The gap in their vaccination rate leaves low-income people once again highly vulnerable to the virus, particularly the more contagious Delta variant. And it poses a major obstacle to the state’s efforts to try to reach herd immunity.

Jacey Cooper, the state’s Medicaid director, called the vaccination disparity a “stark reminder of the inequities within our delivery system.”

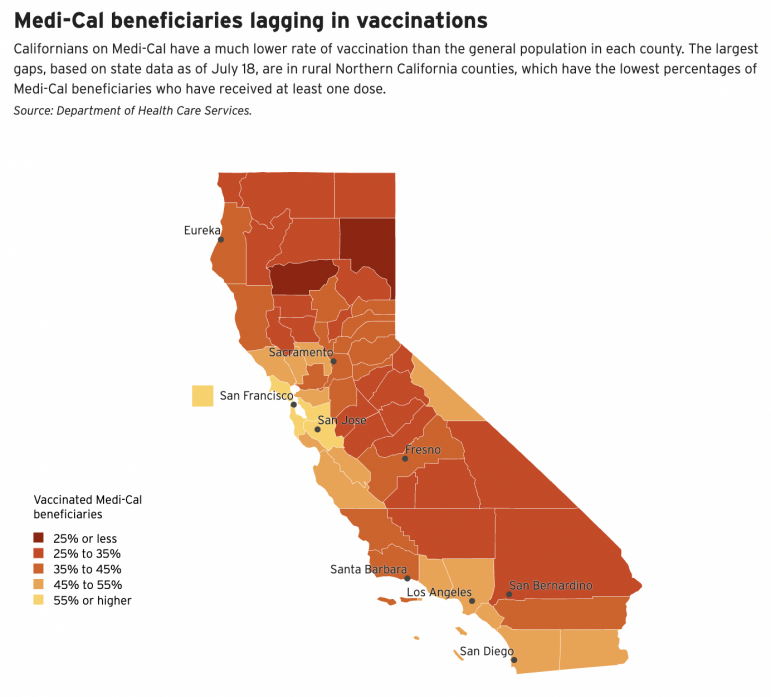

Medi-Cal vaccination rates are under 50% in most counties, but the rates are especially low in rural far-northern counties. In Lassen, Shasta, Tehama, Trinity and Modoc counties, less than 30% of Medi-Cal enrollees are vaccinated. Those counties also have low overall vaccination rates for their entire population.

In Tulare County, which has one of the largest Medi-Cal populations in the state, 48% of the county’s residents have been vaccinated but only 33% of Medi-Cal enrollees. In Los Angeles County, 70% of its overall population is vaccinated, compared to only 49% of people on Medi-Cal.

“It is problematic that this gap exists, but it is consistent with national trends that show people with low incomes are less likely to be vaccinated,” said Laurel Lucia, director of the Health Care Program at UC Berkeley’s Labor Center.

State and county health officials and nonprofit groups have been struggling to reach people in low-income communities. They are trying mobile vaccination clinics, door-to-door canvassing and monetary incentives.

The state’s Department of Health Care Services said it’s doing several things to increase vaccination among Medi-Cal patients, including sharing data with health plans about which enrollees have yet to be vaccinated, encouraging more Medi-Cal providers to sign up to administer the vaccine and working with hospital associations to improve vaccine access in emergency rooms.

Experts said one major reason that many people on Medi-Cal may be unvaccinated is that it is harder for them to take time off work.

“Low-income workers face significant practical challenges. They often have limited time because of multiple jobs, they may lack childcare, spend a lot of time commuting. And they’re worried about missing work, not just for the appointment but also if they have symptoms from the vaccine,” Lucia said.

Amy Jester, a program director at the Humboldt Area Foundation, said it’s particularly a problem among seasonal employees like farmworkers.

For example, in Humboldt and surrounding counties, tourism and agriculture workers are in the middle of one of their busiest seasons. For many of them, taking time off during peak season means losing income.

Nationwide, adults whose employers either encouraged them to get vaccinated or provided them paid time off to recover from side effects were more likely to be immunized, according to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll.

In most California counties, only 25% to 35% of people on Medi-Cal are vaccinated. It’s more than half in only 11 counties, mostly in the Bay Area, but also Orange and Imperial counties.

Alpine County shows the biggest gap — a difference of almost 53 percentage points between Medi-Cal recipients and the county’s total population. The rural county is home to about 1,100 people, so even a few unvaccinated people can make a big difference. Dr. Rick Johnson, the county’s public health officer, said Alpine is seeing high vaccine resistance at American Indian reservations; about 20% of the county’s population lives on a reservation.

In the Eastern Sierra’s Inyo County, the vaccination rate is almost twice as high among the general population than among people on Medi-Cal — 58% compared to 32%.

But the disparity is not just happening in rural, remote or less affluent counties. Marin County has the highest vaccination rate in California — 88% of all eligible residents. But only 61.5% of its Medi-Cal residents had received at least one shot by July 18. Roughly one out of every five Marin County residents is enrolled in Medi-Cal.

San Francisco has the highest percentage of vaccinated Medi-Cal enrollees with 65%, but that’s eclipsed by its overall rate of 84%.

“We believe we can do better, and must do better, to prevent further disparities in COVID infection and death among persons served by Medi-Cal,” a spokesperson for the state health care services agency told CalMatters in an email.

Last month, Ohio’s governor, noting a similar disparity in his state’s Medicaid population, challenged health plans to get 900,000 more Medicaid members vaccinated by Sept. 15. Now, every Medicaid enrollee in Ohio who gets a shot receives a $100 gift card.

Health care providers say they are not surprised that Medi-Cal enrollees have fallen behind on vaccination. State data that tracks vaccination by ZIP code has shown a similar lag in lower-income neighborhoods.

“This is a reflection of decades of issues with inequities” in health care, said Dr. Ilan Shapiro, a pediatrician and medical director for the AltaMed health system in Southern California.

“We saw similar trends with testing — which group was lacking? People in underserved communities,” he said. “We saw it with cases — which group got hit the hardest? People in underserved communities.”

One challenge is the mixed messaging, said Dr. James Kyle, medical director for quality, diversity, equity, and inclusion at L.A. Care Health Plan. He said one of the most successful strategies is direct phone calls to members because it gives people the opportunity to ask questions and ease some of their confusion.

“People are hearing about the Delta variant, about increasing hospitalizations, but at the same time, we’ve reopened businesses, and I think people have genuine confusion… they’re trying to decide what’s the right thing to do, so they’re doing nothing.”