For many, the coronavirus pandemic was expected to last a few weeks, at most. Instead, after more than a year, it’s completely changed higher education in a way that will persist even after campuses have repopulated and California and the U.S. reach some form of herd immunity.

The most significant change has been to instruction and learning, with the vast majority of students and faculty in online classes. But there have been other changes, such as an intense focus on mental health and campuses becoming more flexible with how they operate.

“Higher education isn’t actually known for being nimble,” said Lande Ajose, senior policy adviser for higher education to Gov. Gavin Newsom. “But to take a system, or a set of systems or institutions, where you have an excess of 3 million students and say in the course of two to three weeks, we’ll move students to distance learning is enormous.”

Ajose leads Newsom’s Council for Post-Secondary Education, which assembled a task force to develop a “road map for higher education after the pandemic” that would help aid the state’s recovery. The task force’s recommendations included a common application form for admission to all public higher education in California and support for students’ basic needs, such as internet and financial aid.

These changes would hopefully help to flip what has been a challenging year for many college students. Surveys from the U.S. Census Bureau estimate 30% of students have canceled college enrollment plans for fall 2021.

Students are questioning the value of taking classes online, said Nicole Smith, chief economist and research professor at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce.

Online learning and virtual interactions between faculty and students will undoubtedly become a more regular part of the college experience. There is significant debate, however, over how and to what extent online education should expand.

As part of his 2021-22 budget proposal, Newsom has requested that, by 2022, California’s public colleges and universities permanently increase the share of courses offered online by at least 10% over pre-pandemic levels.

The reaction to that idea has been mixed.

Jason Constantouros, a policy analyst with the Legislative Analyst’s Office, urged lawmakers during a recent state Assembly hearing to reject the proposal and instead require the state’s public colleges and universities to report to the Legislature about experiences with online learning.

“We have concerns with a specific, proposed (10%) target,” he said. “That target appears arbitrary to us and lacking in justification.”

Across the state’s colleges, staff and faculty are exploring how and whether to expand online classes. But none have yet adopted a specific target like the one proposed by Newsom.

Michael Dennin, UC Irvine’s vice provost for teaching and learning, said Newsom’s proposal reinforces a “false dichotomy” by pitting online vs. in-person classes.

Rather than focusing on increasing the percentage of online classes, Dennin said colleges and their faculty should use what they’ve learned during the pandemic to teach each class in the most effective way possible. He predicted that would result in many more hybrid courses that mix online and in-person elements.

“And by doing that, we’re going to better leverage the skills of the faculty because some of us are really good at making videos that engage and that a student can watch and learn something from,” said Dennin, who also serves on UC’s systemwide Academic Planning Council. “And some of us are really good in person.”

Like UC, the chancellor’s office overseeing the state’s 116 community colleges is still studying Newsom’s proposal for a 10% increase in online class offerings, said Marty Alvarado, the system’s executive vice chancellor of education services. However, Alvarado added that she anticipates it will be easy for the community colleges to meet and even exceed that target.

Alvarado noted that, because of the shift to online classes last spring, all of the system’s colleges have now approved the majority of their classes to be offered online, and professional development for faculty in how to embrace online teaching “has been scaled up across the system.”

She expects many classes will be offered in a “hybrid-flex” manner, meaning that students will be given the option to attend fully online, but could also choose to attend in person.

Zahraa Khuraibet, president of the Cal State Student Association and a Cal State Northridge student, said there’s a diversity of opinion from students about whether they prefer online or in-person classes, which is why a hybrid approach appears to be the post-pandemic future, she said.

Khuraibet, who is currently attending her Northridge classes from Texas, said the flexibility is essential because while students miss the “on-campus experience,” there are others who have been thriving in the online environment.

In some ways, distance learning has proven to be more accessible for disabled students, too. As a starting point, lecture classes should regularly be recorded post-pandemic, said David Miller Shevelev, a student at UC Santa Cruz and an advocate for disabled students across the UC.

For students with physical disabilities, recorded lectures are helpful because those students may not always be able to walk to their classroom for a lecture. In Shevelev’s case, he has ADHD and “inevitably misses” 30% of any given lecture.

“Having a recorded lecture means that now I can go back and rewatch that,” he said.

Shifting to more online classes will be a contentious point with faculty. Debbie Klein, president of the Faculty Association of California Community Colleges, which is not a union but represents faculty issues, said she’s in favor of offering online options to students who need the flexibility. She also plans to keep holding office hours on Zoom, which she said is more accessible to many students.

But Klein is opposed to substituting any classes that were once face to face with online instruction. She noted that many community colleges offer high numbers of programs that require hands-on learning, such as nursing and automotive services.

“If each college or district were going to determine how much to increase online, it should be specific to their local community that they serve,” Klein said.

That should also be true at the four-year universities, said Diane Blair, a professor at Fresno State and secretary of the California Faculty Association, the union for faculty across the CSU.

Blair said some courses have a clear in-person element, like science labs, but she said even classes, such as communication courses, which she teaches, should remain primarily face to face. She said she’s realized during the pandemic that giving speeches over a Zoom call isn’t the same learning experience as giving them in front of a live audience.

There are certain elements of virtual teaching that Blair plans to keep using going forward. She may continue allowing students to take quizzes and tests online, having realized that the purpose of an assessment should be to get students “to engage the material,” not memorize it.

But Blair is opposed to any top-down directives to shift classes that were once face to face, to being online.

Private colleges, which have been especially hurt by the pandemic-driven decline in tuition and revenue, see online classes as a way to meet student needs.

“We have learned how to do this and are starting to do it well,” said Beth Kochly, associate provost for curriculum and academic resources at Mills College in Oakland.

The shift to online college recruiting, with virtual college fairs and Zoom visits to high schools had mixed results, counselors and colleges reported. It allowed connections to some high school students who might not otherwise have been reachable due to recruiters’ past travel budgets and schedules, or were ignored in previous years. Yet, student attendance at many such virtual events has been smaller than previous in-person events because students were wary of internet meetings and did not want virtual tours.

Post-pandemic, some aspects of virtual recruiting will continue. Angel Pérez, chief executive officer of National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC), which sponsors fairs, said a hybrid form of recruiting and admissions will emerge.

Zoom meetings, online college fairs and virtual interviews allowed colleges “to talk to students in places and time zones very difficult to get to,” Pérez said. “But at the same time, we have learned that nothing replaces the power of in-person connection.”

Continuing uncertainty about the pandemic’s lasting effect on the economy and health will probably lead more students this upcoming year to stick to colleges close to home, especially local community colleges, according to Margaret Isied, academic counselor at Abraham Lincoln High School in San Jose.

There also is a countertrend: the suspension of standardized testing or a shift to optional tests as an admission requirement at many coveted colleges, which has led more students to try their luck at places to which they might not have applied in other years.

In the early months of the pandemic, one of the most significant moves made by colleges was to abandon the SAT and ACT exams as a freshman admission requirement. Because of the difficulty to test high school students during the pandemic, the UC, for example, made the test scores optional for admission this upcoming fall before dropping the exams altogether. CSU suspended using the exams for fall 2021 admission, but did not make that decision permanent.

And while test-optional debates were taking place before the pandemic, Bob Schaeffer, interim executive director of FairTest: National Center for Fair & Open Testing, said the crisis only “accelerated what was already a fast-moving trend” that will remain. FairTest is an advocacy group opposed to standardized exams.

For example, more than 1,000 universities and colleges nationally were test-optional for admission prior to the pandemic. This past year, an additional 600 colleges chose to suspend testing for at least one year because of Covid-related exam shutdowns. And so far, a total of 1,365 institutions have already announced they won’t require test scores for the high school Class of 2022, according to FairTest.

But distance learning and a year of many institutions offering pass or fail options instead of grading could emphasize the need for testing, said Catherine Hofmann, vice president of state and federal programs for ACT.

“We’re not seeing the demand for testing go down from students,” Hofmann said. “Now more than ever, we need to know where students are because we have had students home for a year … we need assessments to say where they are after a year of pandemic.”

And students will continue wanting to know how they measure up, she said.

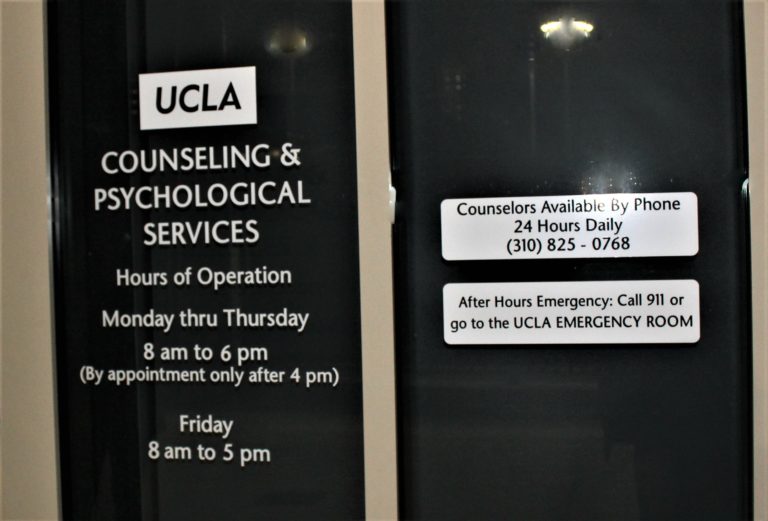

On college campuses, mental health counseling sessions also switched to online and telephone sessions in a hurry last year when the shutdown began. At first, the numbers of students seeking help dropped, but then the numbers climbed up as they began to struggle more with depression, loneliness and other emotional issues related to the pandemic.

“The pandemic put us in a very isolated position,” said Khuraibet, the Cal State student. “A lot of students found campus to be a comforting and safe space, but the pandemic took a lot of that away.”

Khuraibet said she’s spoken with fellow students who are sharing one-bedroom apartments with seven other family members while trying to attend their classes virtually.

“I can imagine how challenging that is,” she said. “But on the flip side, we started to realize we can use virtual spaces to help increase mental health resources.”

Getting on counselors’ schedules and being a Zoom conference away from a meeting, which eliminated travel and time barriers, has helped students with loneliness and pandemic stress, Khuraibet said.

College-level mental health therapists expect that at least some of their counseling sessions will remain online and at a distance even after face-to-face sessions are available. The same is expected for some medical appointments for physical ailments.

“I actually think that telehealth is here to stay long term,” said Gary Dunn, interim associate vice chancellor for student health and wellness at UC Santa Cruz. “Now that we have figured it out and gone through the growing pains of developing the technology and expertise, it’s become a fairly easy option.”

Dunn estimated that about 20% of both mental health counseling and regular medical appointments at campus clinics will remain on video platforms indefinitely to serve students who have come to like that arrangement and find it more convenient if they live far from campus.

In addition, some therapists may continue to work a day or so a week from home, he said.

Nancy Robles, the director of counseling and psychological services at Cal Poly Pomona, said she expects that campuses will be dealing with conflicting emotional issues triggered by the pandemic and online education for a long time. While many students, faculty, and staff will be overjoyed to return to school, sadness will remain about the friends and colleagues who died of Covid-19 and the lost educational and social opportunities. Freshmen and sophomores will especially need attention as they navigate feelings of “a lot of anxiety and fear about what it is going to be like” to attend a real university.

The focus on mental health doesn’t just extend to students. College faculty and staff also face the stress of teaching or working from home, while balancing their own caretaking responsibilities.

CSU Channel Islands is piloting a wellness and self-care program for staff and eventually expand to faculty to help them balance their lives, mindfulness and “combating the 24-7 mentality.”

“Really, this is our attempt to support staff by recognizing whatever we can do to help them be better prepared and support them will, in turn, support our students,” said Toni DeBoni, interim vice president for student affairs at the campus.

The program launched March 1, but DeBoni said the expectation is that it will grow across the campus post-pandemic and perhaps expand directly to students.

One of the largest changes to higher education that will persist is the shift from a “business hour” mindset to addressing student needs anytime.

“Pre-pandemic we were a Monday through Friday 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. system,” said Luoluo Hong, Cal State’s associate vice chancellor for student affairs and enrollment. “When students needed access to advising or financial aid, they would come to us during business hours.”

But the pandemic allowed CSU faculty and staff to have more flexible scheduling as they worked from home. Some employees would work later in the evening because they may have been taking care of their children during the day. That would allow them to accept advising or counseling appointments with students later, Hong said.

Students welcomed that flexibility and eliminating the need to travel to a physical office.

“Colleges have had to up their communication game,” said Stephen Kodur, president of the Student Senate for California Community Colleges and a Reedley College student. Professors had to learn quickly that paper syllabi no longer worked and that students respond better to text messages and social media than they do emails, Kodur said.

“My first counseling appointment in the pandemic was tough,” he said, referring to online counseling over Zoom. “But I just had one a couple of weeks ago, and it was the easiest thing ever.”

In many ways, this flexibility made education more equitable for students who struggled pre-pandemic with balancing child care and scheduling office hours with instructors and advisers.

“I’m a very extroverted person and I hate online classes,” he said. “But I’m glad that I could do them this year because I needed to work around my schedule.”