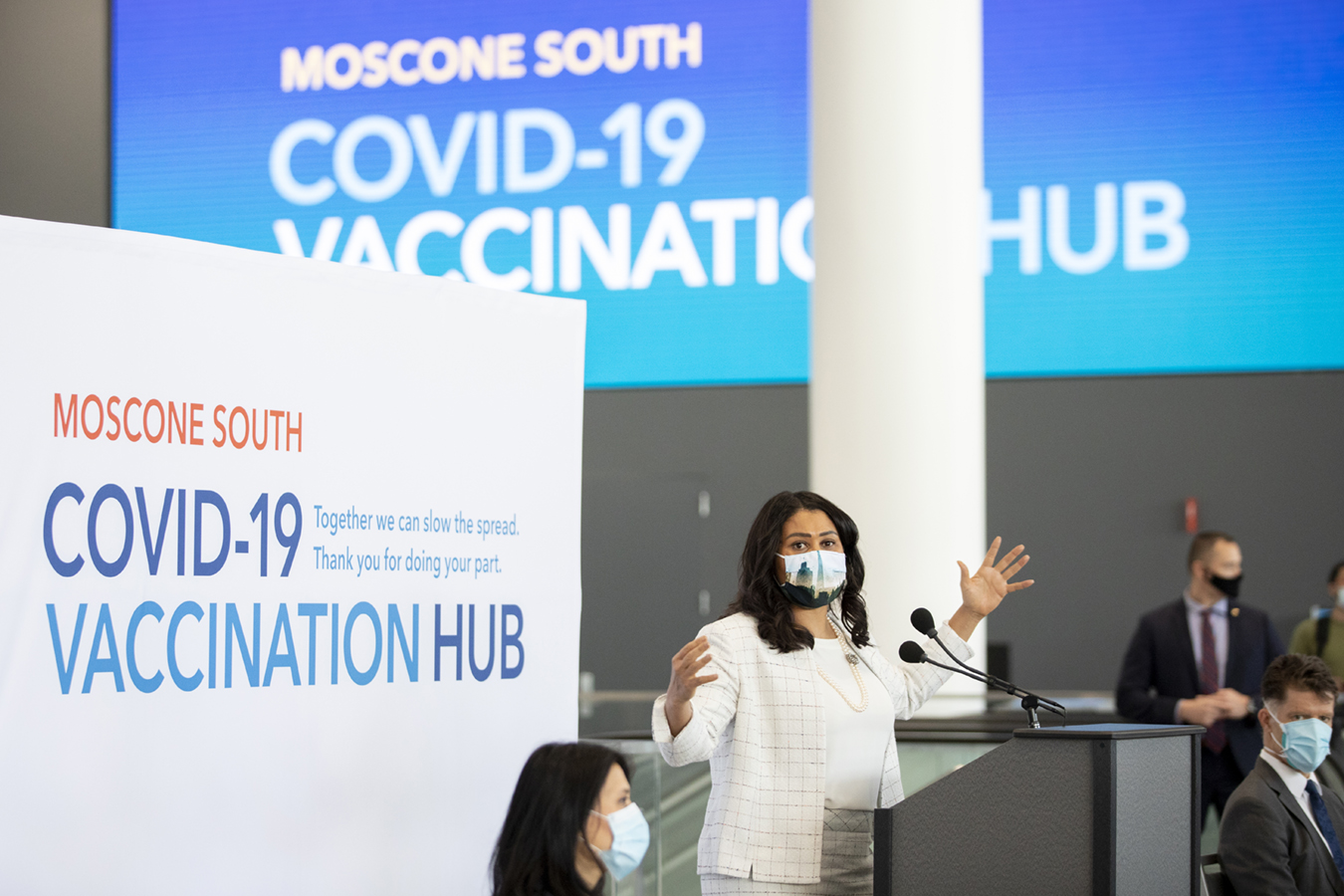

California rolled out a statewide covid vaccination website this week aiming to streamline the appointment process after months of criticism, but the site is riddled with its own snags, preventing many from signing up for shots.

The vaccine sign-up website, My Turn, is the state’s answer to a previous hodgepodge of vaccination appointment systems that residents had to log on to through websites belonging to various hospitals, pharmacies, clinics and many of California’s 58 counties.

The site, created by tech giant Salesforce, is being integrated into insurer Blue Shield of California’s $15 million contract with the state to take over its covid vaccination distribution system.

My Turn is considered a clearinghouse, allowing most California residents to register for covid vaccinations and then receive an alert when they’re eligible to sign up for a vaccine appointment. The app then directs users on how to sign up for available appointments at certain venues.

The My Turn database, however, does not include information about vaccinations available at most pharmacies, or at Kaiser Permanente and Sutter Health hospitals. People who want to get vaccinated at those locations must contact the companies by phone or through their websites.

Like most aspects of state, local and federal government response to covid, My Turn’s rollout has been glitchy. Technology experts say the kinks are not surprising, given the multiplicity of health care information-sharing systems in the state, and a tendency of government officials to overlook the need for consumer usability when building IT systems.

California Department of Public Health spokesperson Darrel Ng said My Turn “is being continually updated to add features to make it easier and more convenient for Californians to make vaccine appointments. If there are technological snafus, they are corrected quickly.” Salesforce did not respond to a request for comment.

So far, more than 650,000 vaccines have been administered via the My Turn system and 600,000 more are scheduled, Ng said. But widespread failures on the site have unleashed a chain of desperate and sarcastic social media responses.

“Here in the Bay Area, with Silicon Valley and all its wealth & technological brilliance, here is how we vaccinate our populace a year into a pandemic,” William Boos tweeted, showing a screenshot of an error message saying an “authentication token” was missing.

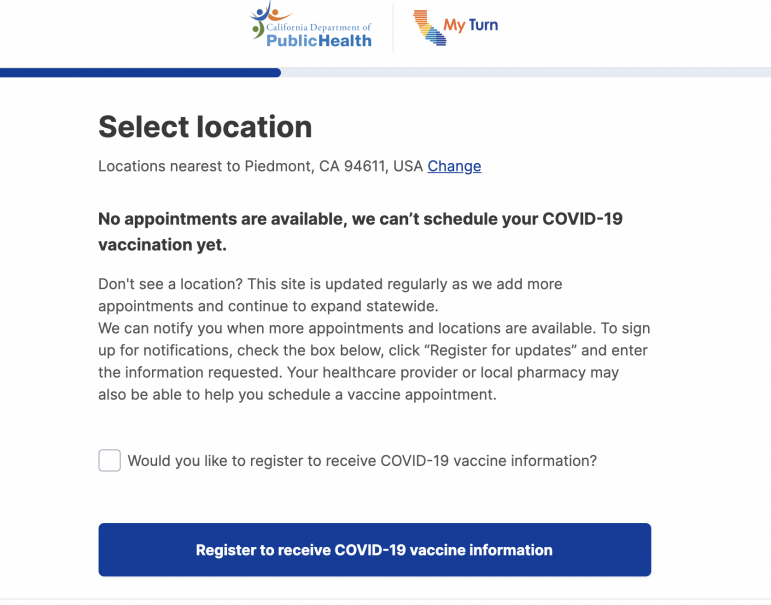

Several Twitter users said they were unable to register for the first shot because no slot for a second shot was being shown as available through the system.

“Seeing spots open on 3/1 on @Walgreens for my category, but no second dose appointments are available. And the MyTurn website shows spots, but has an error message after you choose a time,” tweeted Jennifer Lazo.

Others say the system directed them to vaccination sites with no available slots.

“There are no appointments in San Diego County. Try it yourself. Put in that you are 65+. It’ll say you are eligible and bring you to a site in El Cajon where there are 0 appointments available,” tweeted another user.

One irregularity allowed anyone who had registered in the state to book a vaccine appointment in tiny, rural Kings County. Clinics had to turn away residents who had driven in from neighboring counties, and county officials stopped booking appointments through My Turn entirely until the issue was resolved.

Technological issues with vaccination websites have been an issue nationwide.

In New York, hundreds of seniors lined up one chilly mid-February morning after being told to come for second vaccine appointments between 7 and 8 a.m., only to learn the appointment offer was a computer error. Health officials in Georgia resorted to hand-counting vaccine doses to determine how many available appointments there were.

We asked four health tech experts to explain why My Turn and other systems are not running smoothly. Their responses have been edited for length and clarity:

Arien Malec, senior vice president of research and development at Change Healthcare:

The My Turn website and vaccination dissemination system are products of a reactive, rather than proactive, response that has plagued the medical and tech industries since covid first came on the scene. Everybody is making this up on the fly. My Turn, in particular, is a usability nightmare. The site clearly favors already tech-savvy users and doesn’t appear to have been properly vetted. Tech companies typically spend time and money on testing out software before being released to the general public. My Turn doesn’t seem to pass such muster. There are informal ways of doing usability testing that are relatively cheap. Given all the money that we’re spending on covid vaccination, and given the economic benefit of vaccinating more people, it is cheap at any price.

Hana Schank, director of strategy for the Public Interest Technology program at the New America think tank:

The issues with My Turn and other state-adopted vaccination sites are rooted in government officials’ lack of technological expertise. The people who are making the policy decisions are not equipped to make the tech decisions. Their ultimate goal is less focused on a good consumer experience and more on achieving a tangible result — which, in this case, is getting people vaccinated. Are people signing up? Yes. Are vaccines being distributed? Yes. Done. They think that checks their boxes. A tech issue is never just a tech issue. It’s always a bureaucracy issue, or it’s a silo issue or it’s a lack of expertise. The way the government thinks about success is from another era. Government is really bad at providing a good user experience.

Atul Butte, director of the Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute at the University of California-San Francisco:

Considering where California was just two months ago, when the vaccines first began getting distributed in the state, My Turn should be viewed as a success. While the user interface may contain glitches, a lot of work goes on behind the scenes, trying to get the various counties and their health data aligned in order to get proper vaccination counts for residents. The website draws on four databases: one for ordering the vaccines and tracking shipments; one for inventorying at all sites; the California Immunization Registry, or CAIR; and finally the vaccine appointment scheduler. Each of those databases has many components. CAIR is spread across regions and its system is old; its user-facing website hasn’t been updated since 2013.

Dr. Chris Longhurst, chief information officer at UC San Diego Health:

Even if you had the perfect technology, and everybody was using My Turn, people are still gonna be upset because they can’t get vaccinated. We’re in the valley of despair right now, because we had the weather issues in Texas that impacted not only transportation with the vaccine, but also the manufacturing of some of the vaccine. And then you’ve got the state’s transition to Blue Shield as the new third-party authority, which is bumpy at best. Then you’ve got technology transitions — My Turn, and My Turn integration with electronic health records, that are also bumpy at best. And then you also have the governor opening up a bunch of new tiers for educators and essential workers. There’s no supply to meet that new demand. So that creates tremendous misalignment and frustration.