College access experts attribute the massive spike in applications partially to the elimination of the SAT and ACT in admissions.

Freshman applications to the University of California surged this year, a trend that college access advocates hope will translate into higher enrollments of low-income, Black, Latino and other underrepresented students across the university’s nine undergraduate campuses.

The university received 203,700 applications for freshman admission this cycle, about 32,000 more than a year ago. Experts attribute the increases partially to the elimination of the SAT and ACT as an admission requirement, saying more students likely felt optimistic about their chances of being accepted without having to submit a test score.

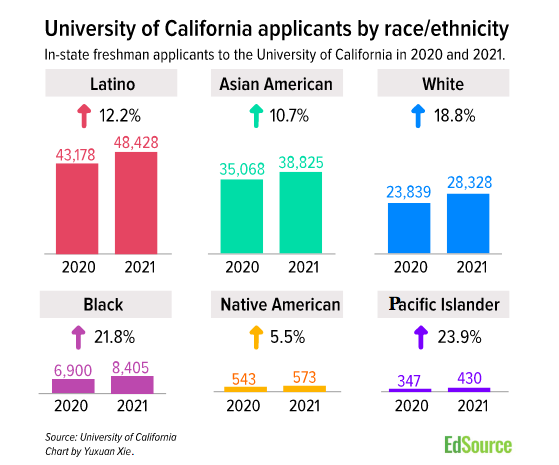

In announcing the massive increase in applicants, UC emphasized that applications were up significantly among Black and Latino students — a welcome sign to critics of standardized tests who point to data showing the exams are biased against those students and have often served as a barrier to them accessing college.

There’s no telling yet, however, whether the increase in applications will lead to a significantly more diverse freshman class this fall. Because freshman applications were also up considerably among white and Asian students, the proportion of Black and Latino students in the applicant pool is similar to last year.

The 2020-21 admitted freshman class was the most diverse in the university’s history. For the first time, Latino students in that class made up the largest ethnic group of students, comprising 36% of admitted freshmen. That reflected changing demographics in California: In 2019-20, Latino students made up a majority of high school seniors.

Still, Latino and Black students remain underrepresented across the UC. And even as UC touts its record-breaking number of applications this cycle, there’s one major caveat: The system’s overall enrollment capacity is not increasing to the same degree, so acceptance rates will likely be lower than usual.

“The numbers being up is fantastic news,” said Michele Siqueiros, president of the Campaign for College Opportunity. “I’ll be ready to pop the champagne when I see what the admission data looks like and what the enrollment numbers look like. It’s still a long way between now and September.”

Also of concern to college access experts is that applications are down at the state’s other four-year university system, the 23-campus California State University. The worry is that some students, optimistic about their chances of being admitted to a UC campus, may not be considering CSU campuses.

Across the UC, the campuses that saw the biggest spike in applications are those that are traditionally the most selective, such as Berkeley, Los Angeles, Irvine, San Diego and Santa Barbara.

Dale Leaman, executive director of undergraduate admissions at UC Irvine, said he expected the surge in applications when the university decided to go test-free.

Some UC campuses initially planned to give fall 2021 applicants the option to submit test scores, instead of requiring them to do so as they have in past years. Then, in the fall, a court ordered that UC campuses could not consider the tests at all this admissions cycle.

“There’s no doubt that many students in the past have not applied to UC who had SAT or ACT scores that they didn’t feel were competitive,” Leaman said.

Other factors may also be at play. The pandemic forced the UC campuses to recruit virtually, which may have increased access to some students.

For years, Natasha Purviance had severe anxiety about taking the SAT or ACT, which she expected would hurt her chances of getting admitted to top colleges.

Purviance is a high school senior in San Diego County from a low-income family. Her parents are divorced and both work full-time. They had little time to help her with her school work, and they couldn’t afford to sign her up for tutoring.

Low-income students generally score worse on standardized tests than their more affluent peers, who are more likely to sign up for costly prep courses and private tutoring.

Purviance lived with her mother during most of high school. English is her mother’s second language, which sometimes made it difficult for Purviance to ask her for help with school work. She speaks some English, Purviance said, but there is still a language barrier.

“My homework, even math, had a lot of words. In order to help me, she needed to digest the word problems and then translate it from her native language to English for me to understand. It was a hassle,” Purviance said.

Purviance took the SAT and ACT several times and scored below average each time. When UC and other universities across the country decided not to require the exams in admissions this year, she was relieved. Purviance ended up applying to four UC campuses: Irvine, San Diego, Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz. She said the strength of her application is her grade point average.

“I felt much less anxious and more confident about the application process,” Purviance said, adding that she is very likely to enroll at UC if she is admitted to one of the campuses.

Josh Godinez, a counselor at Centennial High School in Riverside County, noticed last fall that more seniors were interested in applying to UC campuses than in a typical year.

In past years, students would compare their SAT scores to the average SAT scores among accepted students at competitive UC campuses and decide against applying, Godinez said.

“Now, you’re judging me based on my GPA and my transcript and my personal insight questions,” he said. “It took that intimidation away.”

With colleges holding online college fairs and making virtual visits to high schools, it’s also possible that they reached more students who wouldn’t be able to visit those campuses in a normal year, said Godinez, who is also president of the California Association of School Counselors.

UC San Diego held more than 1,000 virtual high school visits and participated in more than 200 virtual college fairs, said Adele Brumfield, the associate vice chancellor for enrollment management at the campus. The virtual events were typically recorded so students could tune in at their convenience.

“It did expand access. Think about a traditional recruitment year where an admissions office is scheduled to visit a high school at a specific time on a specific day. If a student has an AP biology class at that time, they’ll miss their chance to learn about that college,” Brumfield said.

UC San Diego also set up virtual appointments where students could meet one-on-one with admissions officers, Brumfield said, and spent more time calling students on the phone.

About 118,000 students applied for freshman admission to the San Diego campus, roughly 18,000 more than last year. Last year, the campus enrolled about 6,500 freshmen. The Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles and Santa Barbara campuses also each had at least 10,000 more freshman applicants than a year ago. The other three UC campuses — Merced, Riverside and Santa Cruz — saw smaller bumps in their freshman applications.

Because of the uncertainty of the pandemic, some students may also be applying to more colleges in general to keep their options open, said Michelle Whittingham, associate vice chancellor for enrollment management at UC Santa Cruz.

“One of the things that families learned last year is to keep your options open,” she said. “When they applied in November of 2019, nobody had this pandemic in their minds in terms of what might happen. And so I do think it’s this culmination of intersecting factors that have really led to very different behavior among students.”

Devin Dinh, a high school senior in West Contra Costa Unified, applied to about 15 universities, including five of UC’s nine undergraduate campuses: Berkeley, Davis, Los Angeles, San Diego and Santa Barbara.

He’s feeling more optimistic about his chances of admission than he would have in past years, Dinh said, because he “doesn’t do too well on standardized tests.” He has a strong grade point average — 4.2 — but added that he thinks his personal essays are what will make his applications stand out.

UC Berkeley is his top choice because of the proximity to his home. Dinh grew up just a short drive from Berkeley’s campus. He’s also familiar with the campus because he’s participated in outreach programs between UC Berkeley and his school district.

In the end, however, Dinh’s choice among the schools he applied to will hinge largely on financial aid and the cost of attendance.

“More than anything, I’m trying to look for a school that’s affordable for my family,” he said.

Deciding which students to accept will be a difficult task for UC admission officers, who are also anticipating possible fluctuations in their yield rates, the percentage of accepted students who enroll.

Campuses need to prepare for their yield rates to “swing in either direction,” said Emily Engelschall, the interim associate vice chancellor of enrollment services at UC Riverside. With so many more applicants, it’s possible that more students could be eager to enroll. But it’s also possible that as students keep their options open, some campuses could have fewer students choosing to enroll.

One possible solution to that uncertainty is that campuses could opt to place more students on wait lists than they do in a typical year, Engelschall said.

“We just have to be as prepared as we can for the unknown,” she added.

Meanwhile, with fewer students applying to CSU, it’s possible some students will be left with nowhere to enroll after admissions decisions are made. Applications to CSU were down 5% as of December, though several campuses did extend their deadlines.

The increase in applications to UC is encouraging, especially among Black and Latino students, said Debbie Cochrane, executive vice president of The Institute for College Access and Success. But she added that “we need to see those translate into actual enrollments.”

Cochrane said she’s concerned that there are “far too many applicants” relative to the number of available spots at the UC’s nine undergraduate campuses.

“Combining that with the declining applications at the CSU system, it suggests that those students might not be considering CSU as their backup,” she said. “And that’s a cause for concern. These students are applying to the University of California, so they’re clearly college-interested, and they’re college-ready.” They need to find themselves a seat in an available college, she added.

Godinez, the high school counselor, said he too shares that concern and has spent recent weeks checking in with students and encouraging them to apply to CSU campuses if they haven’t already.

As a counselor, it’s his job to make sure students are casting a wide net of applications “because you never know who’s going to bite,” he said.

“I’m dying to get to the end of the year when we do our exit interviews to see where all of these kids are enrolling,” he said.