As schools grow more familiar with distance learning, one key element continues to baffle even expert teachers: assigning grades in an online classroom.

Many California school districts altered grading policies when schools abruptly closed last spring so that students’ grades could only improve from where they were at just before the sudden stay-at-home order. In those districts, teachers did not lower students’ grades if they were struggling academically.

Other districts switched to pass/fail systems. But this school year, most schools are back to traditional A-F grading scales, creating an all-new learning curve for teachers who must now grade students from behind a computer screen.

The issue is even more pressing for districts that have seen an uptick in Fs and Ds during distance learning. In Los Angeles Unified, California’s largest district with more than 600,000 students, the number of Ds and Fs in grades 9-12 increased by 8.7 percentage points in the fall compared to the same time period last year, according to data included in a district directive to give students more time to pull their grades up.

The data also showed that the gap in the percentage of Ds or Fs between African American (23.2%) and Latino (24.9%) students and their white (12.9%) and Asian (7.6%) peers has widened since last school year. The findings were based on 876,074 total marks that students in grades 9-12 received in the first 15 weeks of the fall term.

Further north in the Bay Area, at West Contra Costa Unified, fall 2020 grades followed a similar pattern. While many students passed their classes, the number of Ds and Fs went up at the high school level, according to Gabriel Chilcott, director of curriculum, instruction and assessment at West Contra Costa Unified. “We have been looking at ways to support students with incomplete work and hold space for them to catch up.”

Sequoia Union High School District in Redwood City similarly saw the percentage of students with more than one failing grade last fall increased from 20% in 2019 to 29%, while Mt. Diablo Unified School District similarly reported that the number of school students failing more than one grade jumped from 19% to 31% in the previous two academic years, the Mercury News reported. And across Sonoma County’s ten school districts, the number of students having at least one failing grade increased from 27% to 37%.

State law around distance learning does not require districts to return to letter grades. However, most districts reverted to their traditional grades this spring to increase student motivation, which some teachers said fell off under a pass/fail system.

They also want to align with the University of California and California State University systems, which typically require A-F grades in student transcripts. But the state’s public universities have not yet agreed upon a common policy when it comes to whether or not they will accept “pass/fail” grades from the 2020-21 school year, complicating plans for districts and families.

CSU will continue to accept “credit” or “pass” grades completed during the 2020-21 school year. However, UC has not officially stated whether it will do the same.

“We are continuing to assess the public health crisis’ impact on student instruction and are reviewing what, if any, accommodations must be made for students moving forward,” said Ryan King, a spokesman for the University of California.

At least one bill making its way through the Legislature, AB 104, attempts to address concerns about grading through multiple approaches, including allowing parents to request to change their child’s letter grades in 2020-21 to pass/fail, and requiring CSU to accept those grades. It would also “encourage” UC to do the same. (The Legislature has limited authority to regulate UC under the State Constitution, but the same restrictions do not exist for CSU.)

The option would largely be targeted towards a high school student “who was on a path to a CSU or UC and had a bad semester because of Covid,” said Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, D-San Diego, who proposed AB 104. “You don’t want a kid who is otherwise college-bound to be prohibited from attending a state school because they have wrecked their GPA. Maybe they couldn’t grasp that foreign language online or harder math course.”

The bill would also allow parents to ask school officials to let their children repeat their grade levels and create a fifth year of high school for students who could not pass their classes during the pandemic.

Research on whether holding students back improves outcomes is mixed, and some experts warn that this approach could disproportionately fall on students from low-income families who have less academic support at home. Last spring, the majority (84%) of U.S. school principals said they would not require students to repeat a grade level if they failed or missed significant class time due to Covid-19 disruptions, according to a survey by RAND Corporation.

During traditional in-person classes, teachers spend more time with students and have more opportunities to talk about issues at home that can affect their academics. Less face-to-face time, on top of the extreme and varied situations students face during the pandemic, has made it more difficult to assess student progress and what they need to succeed.

Now, many districts across California have loosened previously strict rules prohibiting late work with the understanding that students have very different experiences with learning at home.

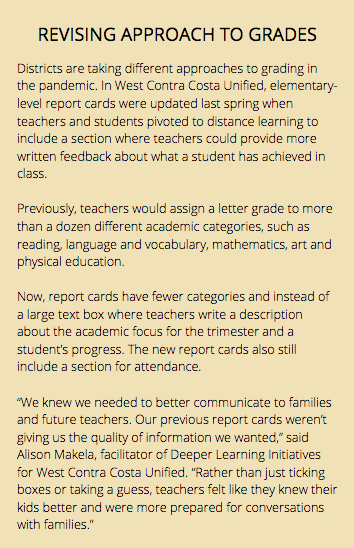

In West Contra Costa Unified, which serves the city of Richmond and surrounding communities in the East Bay, some elementary teachers are using more narrative-style feedback for students rather than a numeric grading scale. That could include remarks about how a student is showing strength and interest in a particular area, or it could explain that a child’s reading progress is slower than expected and ways to incorporate reading practice at home. The idea is to give parents more insight into how their child is doing and help inform instruction moving forward.

At the high school level, some teachers are being more flexible to accommodate students who have weak Wi-Fi or other responsibilities at home. They may accept late work or assign research projects that aim to show mastery of a topic rather than a simple multiple-choice test.

“I now accept late work,” said Asedo Wilson, who teaches ethnic studies and creative writing at Richmond High. “Originally, I didn’t, and a lot of people don’t agree with that policy still. But with distance learning, I leave it open for those who aren’t able to get it done, don’t have a quiet space to work or don’t have adequate Wi-Fi at home.”

The district has also made some other changes. For example, a student has to receive a score of 50% or less to receive an F, instead of 59% or less, which is more common in an A-F grading scale. That change is an attempt to work within the college-required grading system while widening the opportunity for students to pass.

But for working parents like Stephanie Sequeira, who has four children in elementary through high school in West Contra Costa Unified, changes such as allowing late work aren’t enough. It’s overwhelming to come home after a long day of work, cook meals, and help each kid catch up on late work.

“It’s stressful being a working mom and trying to figure out what to do with all four kids, cook and support them,” said Sequeria, adding that some teachers have been more flexible and understanding than others. “I’d do away with grades, really, if I could. I know some students might lose some effort, but there are so many inequities with distance learning.”

California districts are taking a wide range of approaches to address failing grades.

Teachers in Fresno Unified can issue grade changes for students who need more time and are able to display that they have mastered a concept taught in a previous term within the same school year. The district also instituted a winter session focused on credit recovery for high school students.

In Los Angeles Unified, as teachers were gearing up for report cards in December, the district announced it would extend the “no-fail” policy it used last spring and gave students until Jan. 29 to bring up their grades.

“This policy, which gives students an additional six weeks to complete any missing work, acknowledges the unprecedented challenges students are facing while also recognizing their resilience and ability to overcome those challenges with the help of their teachers and family,” L.A. Unified spokeswoman Shannon Haber said.

Meanwhile, San Bernardino City Unified has not instituted any new or relaxed district-wide grading policy changes and instead left those decisions to individual schools and teachers. Officials said getting students to simply log in to class is the “highest concern,” and they are now attempting home visits to check in with families who have been hard to reach.

The pandemic’s impact on learning has not been uniform. A recent study released by the university-based research organization PACE found that low-income and English learners experienced the least academic progress during distance learning in California. Officials in West Contra Costa Unified have seen similar trends play out in their district.

There, teacher-led discussions about grading are aligned with the district’s ongoing work around improving outcomes for Black and Latino students. In particular, racial and other implicit biases can influence the grades teachers assign to their students, which can also contribute to what’s referred to as the “achievement gap,” the gap in grades and standardized test scores between Black and Latino students and their white and Asian peers.

“We saw a widening divide for students who struggle to succeed already,” Chilcott said. “A grade is a summative judgement, but it also needs to be a communication piece with the student and family to drive instruction forward.”

Striking that balance is the ultimate test.

“Grades are important because it’s data that helps you track where you are,” Chilcott said. “But we are talking about kids and how we can help them become the best people they can be.”