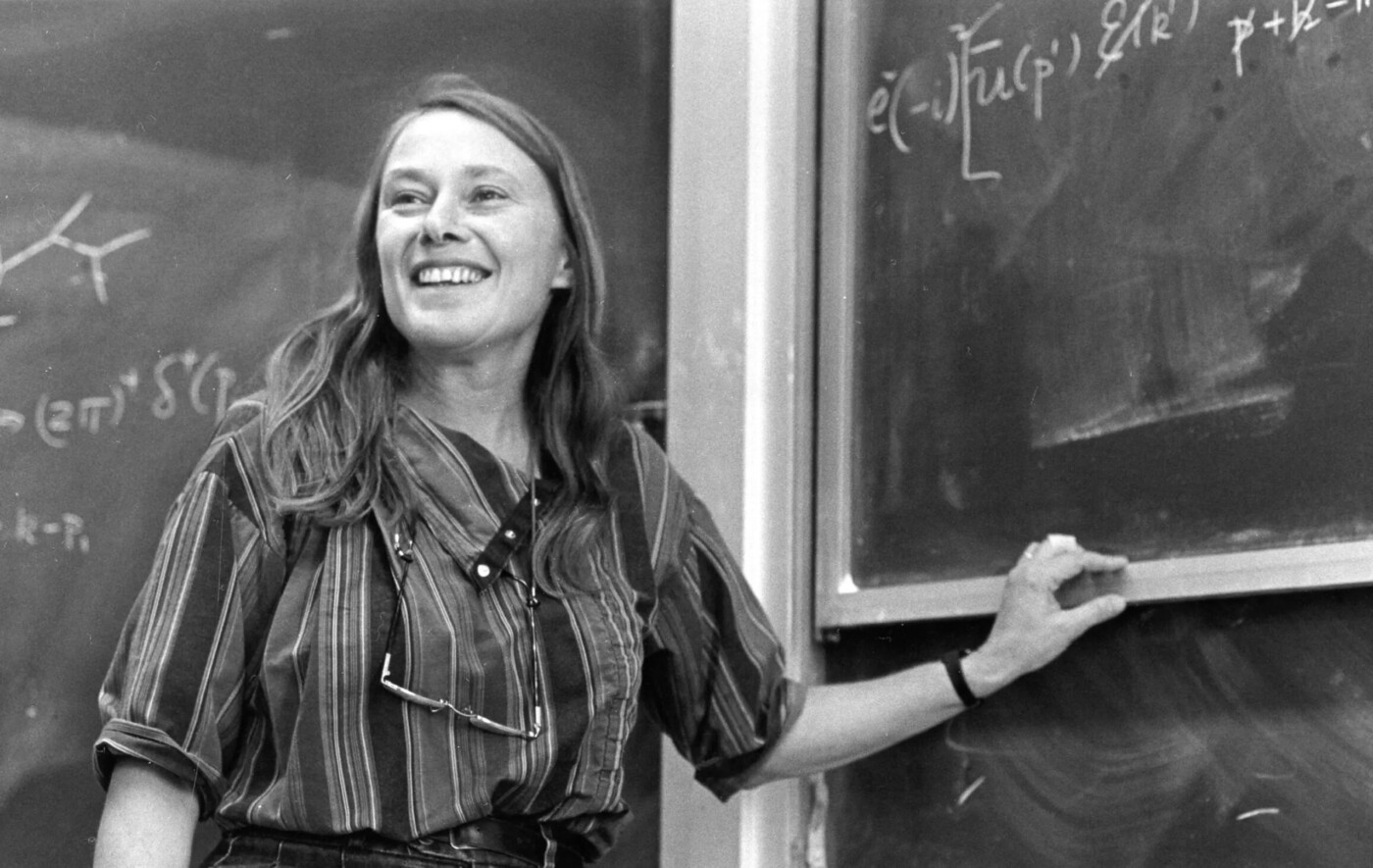

MARY K. GAILLARD, a pioneering theoretical physicist whose mathematical predictions helped shape the Standard Model of particle physics and who defied gender barriers in a male-dominated field, died of natural causes on May 23 at her home in Berkeley.

She was 86, according to a news release on Tuesday from the University of California, Berkeley.

A professor emerita at UC Berkeley, and a senior scientist emerita at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Gaillard carved a path for women in theoretical physics at a time when few were welcomed into the field.

“I was motivated all the time by loving physics and enjoying doing physics,” Gaillard told UC Berkeley News in 2015. “There was a time in my life when I was being a mother, cooking dinner, washing and doing physics and not much else. But it never occurred to me to give up. It was something I loved.”

Her daughter, Dominique Gaillard, recalled, “My memories of my mother include her constantly writing formulas, even on the weekends.”

Overcoming barriers in Europe

Born Mary Katharine Ralph on April 1, 1939, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, Gaillard was drawn to physics from a young age and pursued it against considerable odds. In the early 1960s, after marrying physicist Jean-Marc Gaillard and moving to France, she was turned away from several research positions. Male scientists openly told her that women couldn’t do physics.

Nevertheless, she persisted. In 1964, she completed her first doctorate from the University of Paris in Orsay (now Paris-Saclay University), just two months after giving birth to her third child. That same year, she began working as a visiting scientist at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, where she remained affiliated for nearly two decades — though, unlike her male colleagues, she was never offered a salaried staff position.

“She was very supportive of other women in the field and took us under her wing,” said Nan Phinney, now at Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, who met Gaillard as a graduate student in 1972. At CERN, Gaillard shared office space with other theorists at first, in the basement — and mentored both male and female students.

In 1980, she authored a report on the status of women in science at CERN, noting that only 3% of research staff were women and advocating for equal promotion opportunities, maternity leave, and child care support. Fourteen years later, CERN appointed its first female senior scientist. That woman, Fabiola Gianotti, would go on to become CERN’s director-general in 2016.

“She fought these battles and produced beautiful, important physics while raising three children as a devoted mother,” said Michael Chanowitz, a colleague at Berkeley Lab. “Mary K was a theoretical physicist of great power, gifted with both deep physical intuition and a very high level of technical mastery.”

Champion of quark theory

In the 1970s, Gaillard emerged as one of the earliest and most effective proponents of quark theory, applying complex calculations to predict the properties of yet-undiscovered particles.

“She was one of the early believers in the quark theory before most people had cottoned on,” said Lawrence Hall, a UC Berkeley professor of physics. “She was one of the first people actually doing these calculations, figuring out how a K-meson, or kaon, would decay, for example.”

“She was certainly a pioneer in applying the calculations to phenomenology to actually make predictions,” said John Ellis, her longtime collaborator at CERN, with whom she co-authored 45 papers. Two of those papers have been cited more than 1,000 times — rare for theoretical work.

Their 1975 study of the Higgs boson became a foundational reference in particle physics.

“One of the things that we calculated in that paper was that the Higgs boson should decay into two photons through quantum effects,” Ellis said. “And that decay was one of the key discovery modes when the Higgs boson was discovered in experiments at CERN in 2012. Mary K was certainly the leader in our calculations.”

In 1976, Gaillard, Ellis and physicist Graham Ross proposed a way to discover the gluon, which is a particle that binds quarks inside protons and neutrons. The gluon was experimentally confirmed just three years later.

“She and Ellis had this fabulous collaboration going,” Hall said. “In the late ‘70s, I was a graduate student, and that’s where I was learning what all the exciting stuff was. I was reading all the Ellis-Gaillard papers.”

Breaking ground in Berkeley

In 1981, after years of unpaid status at CERN, Gaillard was recruited to join the UC Berkeley physics faculty amid student pressure to hire a female professor. She became the department’s first tenured woman professor. That same year, she separated from her husband and later married physicist Bruno Zumino, a pioneer of supersymmetry, who followed her to Berkeley.

“The work that she did, certainly with Ben Lee and, dare I say it, with me and our other collaborators, was foundational for the establishment of the Standard Model,” Ellis said. “And then the work she did with Bruno Zumino was also very influential in the formulation of theories with supersymmetry.”

Supersymmetry, which hypothesizes that all particles have heavier “superpartners,” became a key area of Gaillard’s research in the 1980s and beyond. Although experimental evidence for supersymmetry remains elusive, the questions Gaillard pursued — including how the universe favors matter over antimatter — remain central to physics today.

“In the ‘70s and early ‘80s, Ellis and Gaillard were among the first to study many of the great questions that we still can’t answer,” Hall said. “Do the strong and electroweak forces unify? Is supersymmetry relevant? What governs the pattern of quark and lepton masses? What created the baryon asymmetry of the universe?”

Recognition, remembered

Gaillard was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society. Her many honors include the E.O. Lawrence Award and the J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics. She served on numerous national and international science advisory panels and was a member of the National Science Board from 1996 to 2002.

Her memoir, A Singularly Unfeminine Profession: One Woman’s Journey in Physics (2015), chronicled her life in science and the resistance she encountered. The title, she noted, was inspired by a dismissive remark from a high school classmate after she expressed her career aspirations.

“I basically always directed my own research,” she said in a 2020 oral history interview with the American Institute of Physics.

Mary K. Gaillard is survived by her three children — Alain, Dominique, and Bruno — seven grandchildren, and her former husband, Jean-Marc Gaillard. Her second husband, Bruno Zumino, died in 2014. Her brother, George Ralph, died in 1997.

The post One woman’s legacy: Honoring trailblazing theoretical physicist Mary K. Gaillard, 86 appeared first on Local News Matters.