A federal judge in Oakland has postponed a hearing on Elon Musk’s attempt to prevent OpenAI, the owner of ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence models, from shedding its status as a nonprofit corporation.

U.S. District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers pushed Musk’s preliminary injunction hearing from Tuesday to Feb. 4 after Musk’s counsel, Marc Toberoff of Malibu, advised the court that his law firm’s office was “completely destroyed” in the Palisades Fire that sparked last week. The defendants in the case — including Sam Altman, OpenAI and Microsoft — agreed to the postponement.

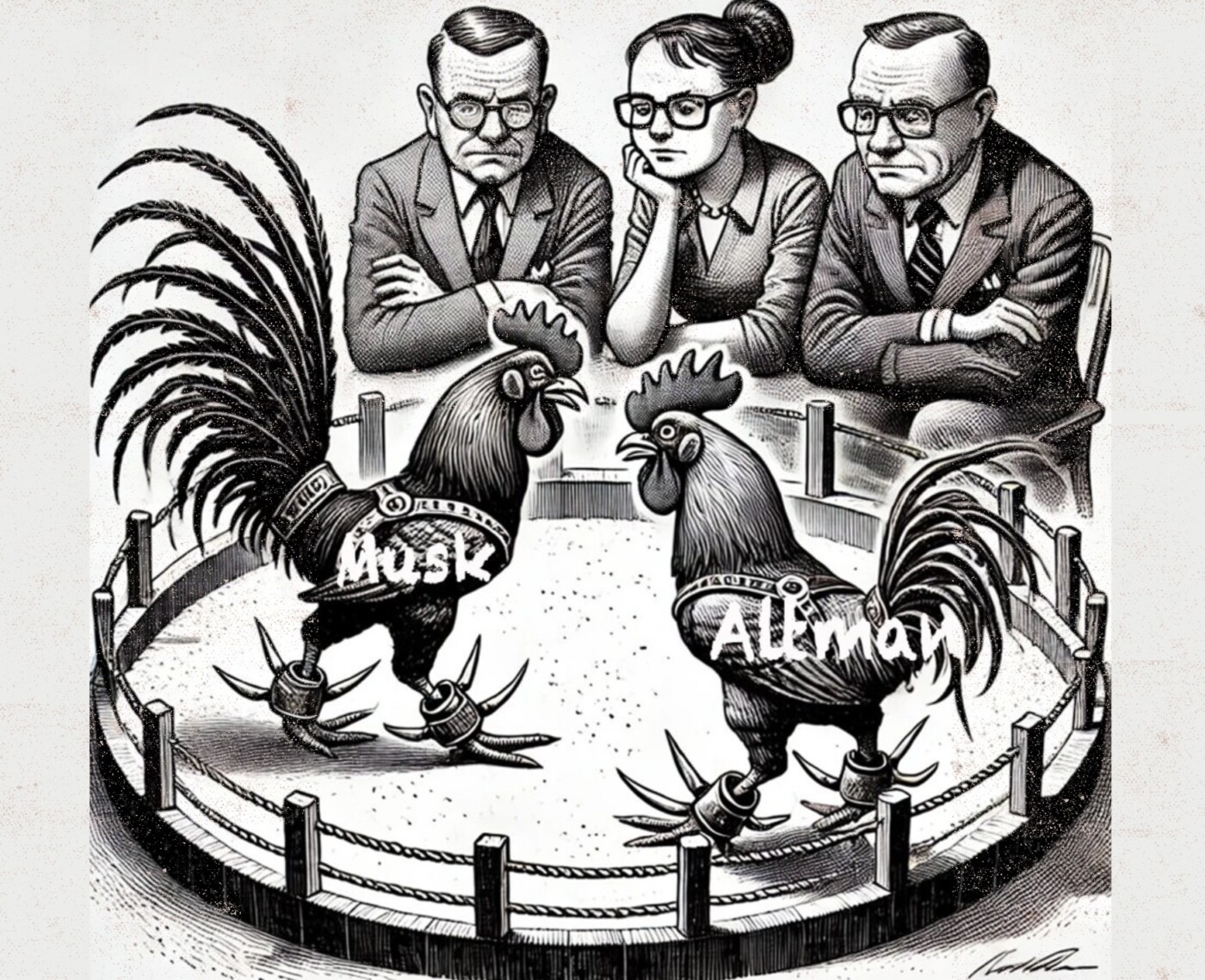

The postponement is the latest wrinkle in a litigation crusade by Musk that began on Feb. 29, 2024, when he sued Altman and OpenAI in San Francisco Superior Court.

Musk’s highly fraught complaint in that case alleged that OpenAI, the nonprofit corporation that he co-founded in 2015 with Altman, had abandoned its initial charitable mission to pursue a potential financial bonanza from its artificial intelligence technology.

According to Musk, the co-founders formed OpenAI as a Delaware nonprofit corporation that would develop artificial intelligence for the good of humanity and would make the technology widely available on an open-source basis so that Google — the leader in the space — would not be able to lock up the technology and use it for private gain.

Musk alleged that he provided OpenAI with tens of millions of dollars in contributions and importantly led the recruitment of the best technologists in the world. He said he relied on the founders’ agreement that OpenAI would not be in it for the money but for the world.

However, in 2019 OpenAI created a for-profit subsidiary and used it to obtain billions in funding from Microsoft. In return, OpenAI gave Microsoft access to the technology and allowed it to blend it into its products. In bombastic allegations, Musk claimed that the noble goals that animated OpenAI’s foundation were being perverted.

Musk’s complaint drew a sharp response. Altman and OpenAI moved to dismiss the case, alleging that Musk was a competitor also developing artificial intelligence and was disgruntled by the fact that his alleged offer to combine OpenAI with Tesla was rejected. In their view, Musk had “abandoned” OpenAI because he thought it would be unsuccessful and only reemerged after it had proven him wrong.

On June 11, on the eve of a hearing to consider the motion to dismiss, Musk voluntarily withdrew the case, only to refile it two months later with a new lawyer in federal court in San Francisco.

Related Stories

The new suit

The new lawsuit has grown substantially in scope from the initial filing. Now Musk raises 26 separate legal theories to support his claims, adding racketeering, fraud, and antitrust violations to supplement his argument that OpenAI’s charitable mission has been abandoned. The complaint also alleges pervasive conflicts of interest and supposed self-dealing by Altman.

On Nov. 29, after media reports that OpenAI was actively pursuing conversion from nonprofit status, Musk filed a motion for a preliminary injunction.

He asserted two claims: that “interlocking” directorships between Microsoft and OpenAI — arguably competitors in developing artificial intelligence products — violated antitrust laws, as did when Altman allegedly told investors who wanted to invest in OpenAI that they could not invest in Musk’s artificial intelligence company, xAI.

Musk also renewed his attack on violations of the nonprofit charter and what he alleged was the “de facto merger” between OpenAI and Microsoft that had reached “the point that Microsoft now exercises effective control over OpenAI.”

Musk asked Judge Gonzalez Rogers to block OpenAI from trying to prevent others from investing in OpenAI’s competitors, including xAI, and stop OpenAI from further efforts to convert to a for-profit status.

As it had in the state case, OpenAI challenged Musk’s bona fides as a litigant. In its view, Musk was just looking to hamstring a competitor.

OpenAI denied that they told investors they couldn’t invest in xAI and pointed out that Musk had raised nearly $6 billion in November 2024 so whatever it had done hadn’t hurt Musk at all. They also argued that the supposedly interlocking directors had long since resigned.

They contended that Musk did not have standing to challenge the governance of OpenAI because he was not a director or an officer of the company anymore.

OpenAI also claimed that many of Musk’s allegations — particularly the ones relating to fraud, and self-dealing — were only alleged “on information and belief,” a term used in legal pleadings when a party asserts something that he or she believes to be true after investigation but cannot definitively prove without more information. OpenAI argued that such statements cannot support a preliminary injunction.

While OpenAI and Microsoft have focused on discrediting Musk, the case has nevertheless attracted the attention of governmental agencies, and they have moved closer to getting involved in one fashion or another.

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk explains Starship’s future to senior U.S. military leaders in Colorado Springs in this 2019 photo. Amid growing scrutiny from states and agencies, an Oakland federal judge postponed Musk’s lawsuit against OpenAI, claiming it abandoned its nonprofit mission. (Illustration by Diane Bakunawa for Local News Matters; photo courtesy NORAD/USNORTHCOM via Bay City News)

The Federal Trade Commission

Last Friday, a few days before this week’s now-postponed hearing, the federal Department of Justice filed a “Statement of Interest” on behalf of the U.S. and the Federal Trade Commission. The statement said that it expressed no view on the truth of the allegations made by the parties, and it did not advocate for a particular result. However, it wanted the court to be aware of its position on the proper way to interpret the provisions of the Clayton and Sherman Acts that Musk had put into play.

Its statement then provided an interpretation that seemed aligned with the interpretation posited by Musk and urged the court to resolve the preliminary injunction “consistent with the legal principles above.”

The Delaware attorney general

OpenAI Inc. was chartered in Delaware. It applied for and obtained nonprofit status as a “tax exempt organization,” meaning that donors to the company were entitled to claim a deduction on their federal returns. The effect was that the public indirectly bore a portion of the funding of the enterprise. OpenAI’s corporate tax returns show $33.5 million in grants and contributions in 2021 alone.

In many states, the state attorney general has broad authority over charitable corporations. Delaware gives its AG general responsibility over nonprofit corporations.

On Dec. 30, 2024, Delaware’s Attorney General Kathleen Jennings asked Judge Gonzalez Rogers to permit her to file a “friend of the court” or “amicus” brief in the Musk lawsuit. In the brief, which was allowed by Gonzalez Rogers, Jennings advised that as attorney general she had an interest in the controversy.

She said that under Delaware law, she had authority to review the proposed conversion of OpenAI into a for-profit corporation. She said that the legality of the transaction would be governed by Delaware law and if she determined that it was not lawful, she had the power to ask for modifications to the transaction or seek an injunction in Delaware state court.

Jennings advised Judge Gonzalez Rogers that she was in “ongoing dialogue” with OpenAI and she was “actively reviewing” the transaction to ensure that OpenAI is adhering to its specific charitable purposes for the benefit of the public beneficiaries, as opposed to the commercial or private interests of OpenAI’s directors or partners.

She said her review would include an analysis of whether the charitable purposes of OpenAI’s assets would be impaired by the transaction and whether OpenAI’s directors are meeting their fiduciary duties.

Jennings took no position on the preliminary injunction but wanted Gonzalez to be aware of Delaware’s interest.

The California attorney general

Meanwhile, in California, Attorney General Rob Bonta was technically a party in the case after having been joined in the case as an “involuntary party.” (Before the suit, Musk asked Bonta for permission to sue “on behalf of” OpenAI on the theory that its alleged conflicts of interest and self-dealing prevented it from asserting its own rights. When Bonta did not answer the question, Musk named him as a party.)

But whether or not he is a party, Bonta, like Jennings, has an interest in the case.

On Aug. 28, 2017, OpenAI Inc. was registered with the Registry of Charitable Trusts maintained by California’s attorney general. The registration requirement, subject to some exemptions, applies to charitable corporations “holding assets for charitable purposes or doing business in the State of California.”

When the act applies, “The Attorney General may investigate transactions and relationships of corporations and trustees subject to this article for the purpose of ascertaining whether or not the purposes of the corporation or trust are being carried out in accordance with the terms and provisions of the articles of incorporation or other instrument.”

Bonta has not filed any pleadings that reveal what role his office will seek to play in the ongoing drama.

Rose Chan Loui, a lawyer who serves as executive director at the Lowell Milken Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofits at the UCLA School of Law, has spent her much of career on issues of nonprofit corporation governance.

Loui said that as the state of incorporation, Delaware’s focus is on the corporation’s governance and its legal “purpose,” that is, what its charter says it is to do. California, on the other hand, has jurisdiction over the company’s charitable assets and how they are used.

She said that in the past, “California has been quite aggressive about exercising its authority.”

California is usually very concerned with whether statements to the public are being complied with. Loui said that when OpenAI formed as a nonprofit, they got a “halo effect” that likely helped them recruit engineers and scientists because OpenAI was developing AI “with an eye to benefitting all of humanity.”

Loui thought there was a role for each of the states and thought it likely that they were talking with each other to work out a common position.

She did not know what that position would be because OpenAI’s charter gives it the mission of developing artificial intelligence safely and with an open-source approach. She wondered whether that purpose could be satisfied simply by the payment of a large sum for the charitable assets.

Others weigh in

The national consumer advocacy organization Public Citizen had advice for the attorneys general. In a Dec. 17 letter, it said that OpenAI had surrendered its nonprofit mission and should be “dissolved” and its assets devoted to charity.

If OpenAI wants to convert to a for-profit organization, Public Citizen urges that payments on account of the charitable assets must be made to “a new, independent charitable enterprise completely separate from OpenAI.”

In its view, the alleged conflicts and self-dealing between OpenAI (the nonprofit) and Altman and the for-profit OpenAI are so pervasive that it is not possible for OpenAI (the nonprofit) to take an independent position.

Public Citizen does not say how much OpenAI should receive for its assets but says the amount at bare minimum would be $30 billion.

The post Oakland judge postponed Musk suit against OpenAI even as interest in the case gathers appeared first on Local News Matters.