WHILE ONLY A fraction of the country’s 50 million public school kids headed back to school in-person this month, many have already found themselves back at home.

Within two weeks of opening, multiple states reported school-based COVID-19 outbreaks, and thousands of students and school staff have been quarantined following possible exposure to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Many of these districts are in areas with high community spread of COVID-19, and some didn’t enforce social distancing or require face masks.

Our team of infectious disease epidemiologists collected data in the San Francisco Bay Area and ran computer simulations to examine how school closures and reopenings can affect the spread of COVID-19.

What we learned points to three key strategies for minimizing the risk of coronavirus transmission while allowing kids to get back to learning, socializing and thriving in their classrooms. Those strategies involve lowering community transmission, minimizing interaction between students and teachers of different classrooms, and focusing on elementary schools.

Lessons from spring’s school closures

In mid-March, the Bay Area was one of the first places in the U.S. to close its school buildings and switch to remote classes. By the end of the spring semester, it had confirmed more than 14,000 COVID-19 cases and nearly 4,000 deaths.

Our model used data from the Bay Area, including on social contacts among children and adults during shelter-in-place, to estimate how much the virus is expected to spread. We estimate that if all K-12 schools had remained open for the full spring semester, the region would have had an additional 13,000 cases — nearly doubling the case count — and added more than 600 deaths to the devastating toll of the pandemic.

Clearly, school closures made an important contribution to slowing the coronavirus’s spread, but not all schools contributed equally.

We found that closing elementary schools averted just 2,000 cases, compared with more than 8,000 cases prevented by closing high schools. To put that in perspective, our model showed that workplace closures averted about 16,000 cases.

High schools and teachers face the highest risk

What does all this mean for the prospects of K-12 schools reopening this fall?

If community transmission remains high — as it has in the Bay Area — in-person classes carry substantial risks.

We estimate that an additional 1 in 3 teachers, 1 in 8 students, 1 in 12 family members, and 1 in 16 community members in the Bay Area would get infected and experience COVID-19 symptoms during the fall semester if area schools reopened without safety measures. More than 1 out of every 100 Bay Area teachers would be hospitalized.

The risk to teachers would be especially concerning in the area’s high schools, where we estimate nearly half of teachers would develop COVID-19 symptoms.

The predictions also show that risk is not the same across all levels of schooling.

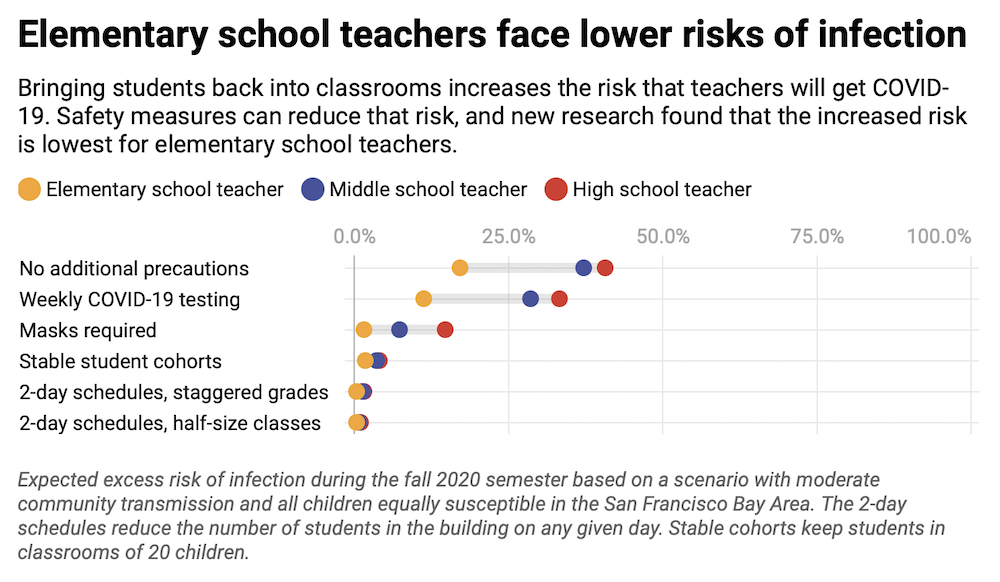

Our models show that the excess risk to elementary school teachers is five to 10 times lower than the risk to high school teachers. Our findings, released in August as a preprint study, reinforce what other researchers have concluded: that elementary schools have the best chance of reopening with the least risk.

Why do elementary schools have a lower risk?

Elementary schools have fewer students than high schools, so it’s less likely that an infected student will enter the classroom. Since elementary students don’t move between rooms as often, there also is less opportunity to seed a school-wide outbreak.

Additionally, studies suggest that younger children may be half as likely to get COVID-19 after exposure to the virus than adults, potentially because children have fewer of the receptors that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to infiltrate cells in the body. If infected, children are more likely to have mild symptoms or no symptoms at all.

Some studies have suggested that younger children don’t transmit the virus as easily, but that children over 10 years may pass on the virus as efficiently as adults. Scientists’ understanding of how susceptible children are to the virus and how infectious they can become is rapidly evolving.

If schools are closed, elementary school students are also more likely to be exposed to other people in the community, particularly through day care and running errands with their parents.

We surveyed hundreds of Bay Area households to see how students and families were able to shelter in place during long-term school closures. Before the pandemic, older children ages 13-17 were found to have more contacts than younger children, ages 5-12. We found that during school closures, however, younger children had twice as many interactions with other people as teenagers.

More precautions are needed

To safely reopen schools, communities must reduce their transmission rates. That alone isn’t enough, though. Safety precautions, such as wearing face masks and social distancing, are also necessary.

Our models predict that even if community transmission is moderated, opening a Bay Area elementary school of 350 students without safety measures would result in 1 in 25 teachers becoming infected. The risks balloons to nearly 1 in 5 if young children are found to be as efficient at acquiring the virus as adults.

We found that the following safety measures would allow schools to keep the number of school-attributable infections among teachers below 1%:

- Keep children in small class groups of no more than 20 students.

- Sharply reduce interactions between class groups, including keeping teachers apart from each other.

- Require everyone to wear a mask.

South Korea is one example of how these measures can be successfully implemented. In many schools, students eat lunch at tables with plastic barriers, and lunch times are different for each grade. Hallways are one way, and arrivals are staggered. Teacher-to-teacher socializing is limited. Everyone wears a mask.

Which neighborhoods to focus on first

In deciding whether to reopen schools or keep classes online, the impact on students’ learning is also important. In communities with the highest rates of COVID-19 transmission, schools often have fewer resources that would allow them to reduce class sizes, provide masks and find space for distanced lunches and recess. At the same time, their students may lack support at home during the day to help them succeed in an online learning environment.

That and our findings suggest that communities should focus first on developing pandemic-resilient classrooms in elementary schools in high-transmission neighborhoods, particularly those with low-income families.

Jennifer Head is a Ph.D. candidate at University of California, Berkeley. Justin Remais is an associate professor and chair of Environmental Health Sciences at University of California, Berkeley. The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

I really do wish that it was a simple matter of throwing more money into designing functional and safe classrooms. South Korea is not the best example because many Asian cultures teach respect and self discipline from a very young age. Both are key requirements for resuming in person learning. In addition to conflicting ideas of letting kids be kids, not making parents vicariously responsible for the actions or inaction of their children, and America’s strong emphasis and sometimes unbalanced emphasis on individuality, low income areas probably have undiagnosed or untreated cases of attention deficit-related issues among the students. Diseases don’t discriminate but healthcare providers do especially if the children do not have strong advocates at their side. The low income classrooms will be ok once people stop turning a blind eye to discrimination in the provision of basic services. Let’s start there instead of simply throwing more money around.