At lunch last school year, sixth graders at Bayside Middle School in Virginia Beach could be heard shouting “Uno” and tapping out sound patterns on a Simon game console.

Getting students hooked on classic games is one way Principal Sham Bevel has tried to soothe their separation anxiety after the district banned cellphones two years ago. At Bayside, students must keep the devices in their lockers during school hours.

But convincing kids there’s something better than posting TikTok videos or browsing friends’ Instagram posts is an ongoing struggle.

“Cellphones are to children what the blanket was to Linus,” Bevel quipped.

Cellphone bans during school hours have gained momentum in recent months, with states like Virginia, Ohio and South Carolina taking action and the Los Angeles and New York districts moving in that direction.

But schools may find that deciding to remove phones is the easy part. The real test is finding a way to secure and store them that both staff and families find acceptable. Complete bans leave some parents nervous, but partial restrictions often put teachers in the uncomfortable position of policing the rules during valuable class time.

“All of these have pluses and minuses,” said Todd Reid, spokesman for the Virginia Department of Education. The agency is gathering public comments on how best to implement Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s July 9 executive order to have phone restrictions in place by Jan 1. Officials will release guidance in mid-September. “All of them really come down to how the policies are implemented.”

One approach to banning phones, storing them in students’ lockers, can be hard to enforce, said Kim Whitman, a co-founder of the Phone-Free Schools Movement.

“Teachers say that students ask to go to the bathroom and then go get their phones,” she said. “It still allows negative activities to happen between classes — cyberbullying, planning fights and others videoing them.”

Sheila Kelly, a board member for Arlington Parents for Education, a Virginia advocacy group, raised another practical issue: Not all schools have lockers. What’s most important to her is that schools restrict phone use not just in class, but during breaks.

“It’s during those in-between times … that students can experience the mental health advantages of phone-free interactions, allowing them to grow socially and emotionally,” she said.

‘Loopholes’

A growing number of schools say Yondr pouches, which cost about $25 per student, accomplish that goal.

The neoprene sleeves, often used at live music and comedy events, lock with a magnetic closure and can be reopened with a device usually mounted near a school exit. Districts among the company’s top customers include Cincinnati and Nashville, according to GovSpend, a data company.

In June, Delaware Gov. John Carney signed a budget that includes $250,000 for a Yondr pilot program in middle and high schools this fall. Last year, the company earned $3 million in government contracts — doubling its business from 2022, GovSpend shows.

In New York City, where Chancellor David Banks is currently hammering out the details of a ban expected next year, some teachers prefer Yondr because it takes them out of the enforcement business: Students lock up their phones in a pouch when they come to school in the morning and can’t remove them until they leave in the afternoon.

Vinny Corletta, a Bronx English teacher, used to work in a school where teachers employed incentives to discourage phone use. Kids could rack up points for prizes — from pencils to sneakers. But frequent reminders still took time away from instruction.

“I’m a teacher; I don’t want to hold 30 cellphones for students all day,.” he said.

Now he teaches at Middle School 137, where students put their phones in a Yondr pouch when they arrive and then store them in their backpacks. He thinks that even if they can’t access their phones, students prefer having them close by rather than in a locker or classroom storage container.

But no method is foolproof. Students have been known to disable Yondr locks or even surrender a dead older phone while stowing their current model in a backpack.

“Kids are so smart — sometimes more than adults — and always find loopholes,” said Elmer Roldan, executive director of Communities in Schools of Los Angeles, a nonprofit that provides support services to students in low-income schools.

He’s worried about students being “policied, patrolled and punished” for violations, recalling the Los Angeles district’s failed iPad rollout in 2013. Students easily broke through the security firewall and used the iPads to play online games like Subway Surfers and Temple Run. The district stopped allowing students to take them home.

“I thought the district should’ve hired those kids … to teach district staff about technology security,” he said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if schools exhaust their energy trying to implement this ban.”

Los Angeles officials have until October to specify how they’ll enforce a ban the board approved in June.

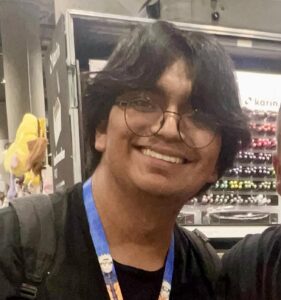

But some L.A. students think adults have blown the issue out of proportion. Alejandro Casillas, who will enter 11th grade at Hamilton High School in Los Angeles this fall, said teachers already confiscate phones if they see them more than once during class or offer extra credit to limit use. He gave up his phone once to get the additional points.

“I think this image of phones being a distraction is over-exaggerated,” he said. “If the district were to take away cellphones, I think some students would still be distracted.”

Students might think they’re good at multitasking, but experts say that allowing them access to phones in class prevents them from focusing deeply on their lessons. Research also points to increases in test scores following phone bans.

Israel Beltran, a rising sophomore at Mendez High School, said he doesn’t use his phone in class except when teachers allow it during breaks. At that point, he often turns to funny videos on YouTube. But the idea of a total ban makes him feel like he’s back in elementary school.

“When we had a toy or something we shouldn’t bring to school, they usually would take it away from us and give it back at the end of the day,” he said.

‘A lifeline’

Parents have been among the most divided over districts’ efforts to ban students’ phones. The Phone-Free Schools Movement has a team of 80 ambassadors across the country, mostly parents who track district policies and promote cellphone bans for students in their communities.

But a recent national survey from the National Parents Union showed that while parents support “reasonable limits” on use, a majority — 56% — think students should occasionally have access during school hours.

That’s especially true for parents whose children have disabilities or health issues.

In Los Angeles, Ariel Harman-Holmes doesn’t want an across-the-board ban. She was afraid her son, who will enter sixth grade at the Science Academy STEM Magnet this fall, would lose a phone. So she gave him an Apple Watch, with its own number and data plan. With ADHD and a condition called face blindness, he sometimes can’t recognize people or even familiar places — a limitation that was especially stressful when people wore masks during the pandemic.

“He couldn’t even tell who was an adult and who was a child. He didn’t know who to trust,” she said. One day he used his watch to call his parents, who helped him get reoriented. Now she plans to have use of the watch written into his special education plan as an accommodation. “I feel like kids with certain disorders or disabilities, like autism, anxiety, possibly depression, need a lifeline to their parents.”

Regardless of which method districts adopt, parents have found that enforcement can be inconsistent.

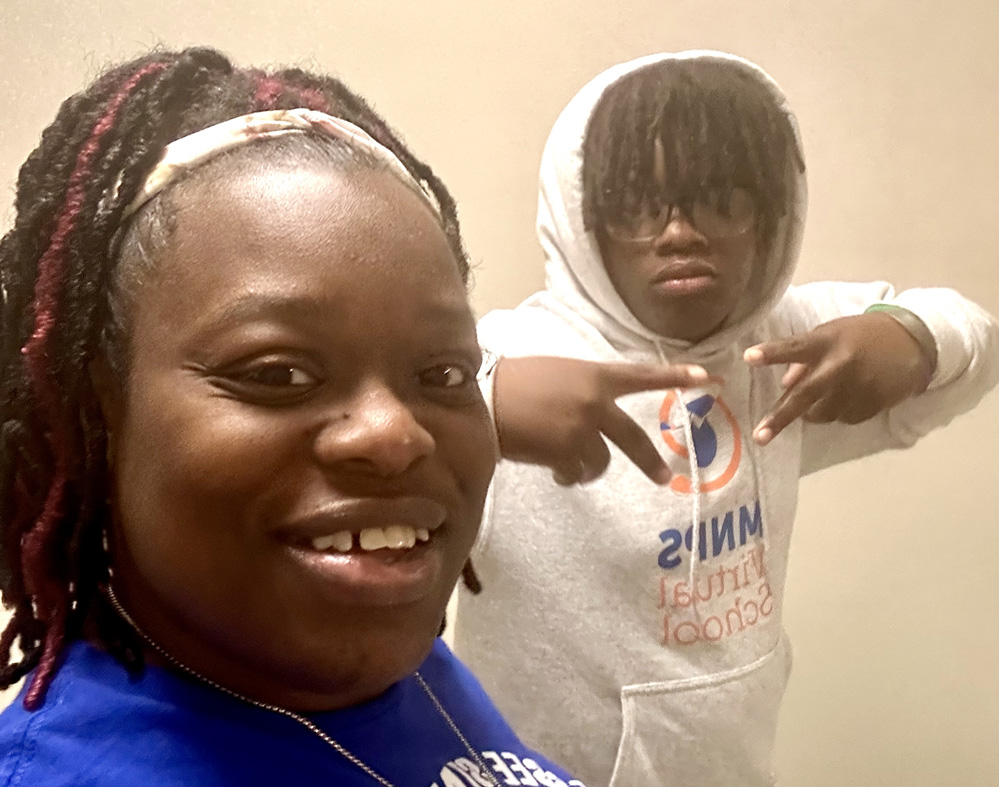

Victoria Gordon, whose son Malik attends Republic High School, a Nashville charter, supports leaders’ efforts to minimize use during class. The school’s official policy prohibits students from accessing social media during school hours. But visiting one day last year, she saw her son using his phone in class. Sometimes, she glimpses photos he posts during school hours.

“Why is my child on Instagram at 10 o’clock in the morning?” she asked. “They’re not implementing what they’re saying.”