It has been 13 years since Nick C. sat in an Alameda County jail at the age of 24, facing decades in prison and the prospect of never seeing his kids again.

He looks back on it as a turning point: Years in juvenile detention and a young adulthood spent dealing drugs culminated in a “bar fight gone sideways.” Charged with attempted murder, he pleaded guilty to assault with a deadly weapon, according to court records.

In the following years, he took anger management classes, earned a GED and worked as a dishwasher after a higher-paying maintenance job offer fell through when his background check turned up with a violent felony, he said. Then an electricians’ union gave him an apprenticeship without caring about his record. Now he works nights, has his kids back and recently bought a house with his wife.

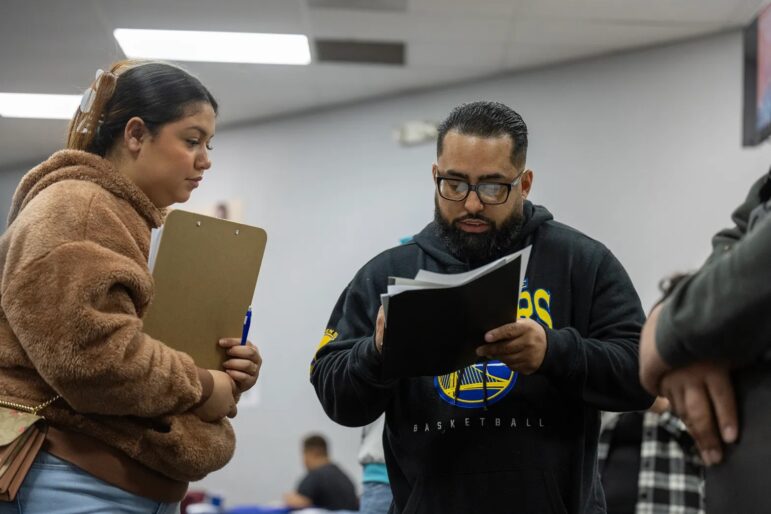

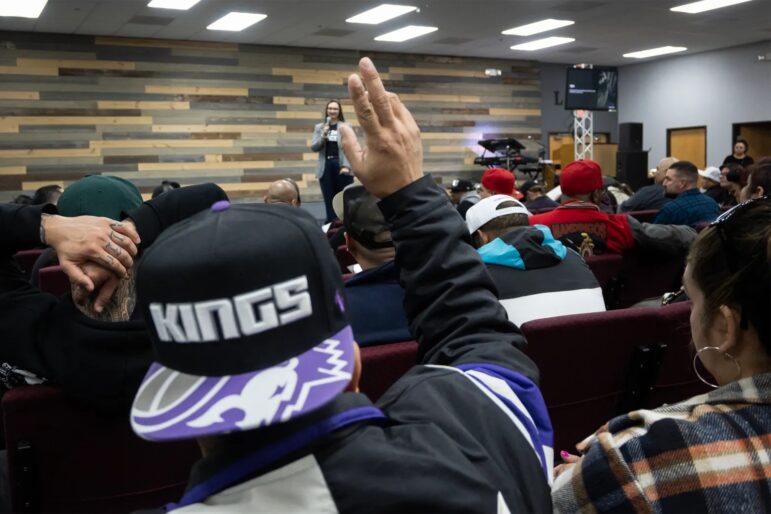

The final step Nick wants to take is to clear his record, the 37-year-old said on a recent Saturday morning, standing in line inside a south Sacramento church with nearly 200 fellow Californians with felony convictions.

He was waiting for a notary to scan his fingerprints, which would generate a record of his California arrests and convictions for a nonprofit attorney to review. He said he’s stayed out of trouble since the assault, which would likely make him eligible under a recent law to ask a judge to dismiss the case and seal it from public view. His record blocks him from certain job sites, such as government construction projects, he said, so he hopes an expungement would open more professional doors.

“It’s to show my kids that my past is my past, and that’s where it’s going to stay,” said Nick, who wanted to be identified only by his first name to avoid jeopardizing job opportunities if the expungement is successful.

California has allowed expungements of misdemeanors and some lower-level felonies, but not crimes that would be serious enough to send the offender to prison.

That’s no longer the case: Under Senate Bill 731, which went into effect in mid-2023, Californians with most kinds of felony convictions, including violent crimes, can ask for their records to be cleared. Sex offenses are the primary exception. To be eligible, applicants must have fully served their sentences, including probation, and gone two years without being re-arrested.

Passed in 2022 mostly along party lines, the law came after years of efforts to reduce the burdens that a criminal record still places on Californians’ job and housing opportunities. It was among the broadest expungement laws in the nation, including about one million residents with felony convictions, said Californians for Safety and Justice, the advocacy group that sponsored the bill.

The law goes even further, directing the state Department of Justice to automatically seal from public view non-serious, nonviolent and non-sexual felony convictions when the defendant has completed their sentence and not been convicted of another crime in four years. That provision was supposed to begin last year, but lawmakers agreed to delay it until this July.

In the meantime, those hoping to get their convictions cleared are turning to the courts, just as the public and some Democratic leaders have taken a tougher stance on crime. Applicants have since last year filed a trickle of expungement requests with the help of legal aid attorneys, public defenders and nonprofits such as the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, which provides prison re-entry services and offered the free fingerprinting in Sacramento this month.

“They served their time, and they’ve done their own internal work and diligence to come out the other side,” Elizabeth Tüzer, the coalition’s expungement legal project manager, said of her clients. “It doesn’t mean they shouldn’t have a job, or be able to survive or have housing.”

For these requests, judges have the ultimate say, and can consider evidence of rehabilitation as well as any opposition from prosecutors.

It’s not clear how many of these felony expungements have been granted. The state Judicial Council isn’t specifically tracking it, and most of the superior courts in the state’s largest dozen counties could not immediately distinguish them from other cleared cases. Since mid-2023, there have been 26 felony expungements in Sacramento County, 72 in Kern County and 48 in Riverside County, according to court spokespersons.

The Anti-Recidivism Coalition has helped clients file nearly 200 requests statewide, Tüzer said, with about half granted so far.

The expungements, which state law calls “records relief,” don’t erase the cases entirely.

The records will still be kept by the state justice department, which will share them with other government agencies, police and prosecutors if an ex-offender is arrested again, or with the state Department of Education if the ex-offender applies for a school job. Under the law, expungements also don’t allow someone to own firearms again, or avoid disclosing a conviction if they run for public office or apply for a job with law enforcement.

But they do mean local courts are required to block cleared cases from public searches and from the background check companies commonly used by private-sector employers and landlords.

Saun Hough, a manager at Californians for Safety and Justice, said the benefits extend beyond those with a job application on the line. Old criminal records hinder Californians from fully participating in society in a variety of ways, he said, from chaperoning their children’s field trips to holding positions in a homeowners’ association.

“Peace of mind, that’s the biggest of all the new doors that are open,” he said.

For Alexis Pacheco, a friend of Nick’s in San Francisco who told him he may be eligible, expungement provided psychological relief.

Pacheco, 39, recently won a judge’s order to seal an old felony that she said stemmed from a fight with an ex-husband. The conviction hung over her head in subsequent child custody disputes, she said, and for years after her release from jail, she worked at a storage facility in a job a relative helped her get. Her career was stagnating, she said, but she was “scared to go for more, scared they’ll run a background check.”

She now works at a nonprofit and attends college, hoping to one day enroll in law school. To ask for her record to be sealed, she said an attorney directed her to write a letter detailing how she’s turned her life around. A San Mateo County judge granted an expungement in December, according to a court order she shared with CalMatters.

“If people don’t know your story you’re just this person on paper,” she said. “When I got the letter, I cried. It’s no longer, you’re just this person.”

When the automatic felony expungement begins in July, about 225,000 Californians will qualify, said Californians for Safety and Justice, with more becoming eligible in the future as more time passes after their convictions.

Automatic expungement eliminates the need for defendants with lower-level convictions to find an attorney, pay filing fees or go before a judge. Criminal justice reform proponents have pushed for these “clean slate” bills across the country. They’ve cited a 2020 Harvard Law Review study that found few eligible ex-offenders apply for expungement, and argued it’s fairer to instead grant relief to everyone who qualifies.

California began automatically sealing old misdemeanors in 2022, in response to a prior law. In the first six months, state records show the Department of Justice directed county courts to shield 11 million cases from public view, helping six million defendants. The agency called it the “the largest record relief carried out over such a short time period in U.S. history.”

“Automatic record relief is ultimately about equity,” Attorney General Rob Bonta said in a statement emailed by his office Wednesday. “Individuals who have served their debt to society deserve a second chance, and they should not have to hire an attorney to get that second chance.”

As a state Assemblymember in 2018, Bonta authored a law to automatically clear cannabis convictions. He also supported the automatic misdemeanor sealing law.

To carry it out, his department booted up a computer program that every month scans through every criminal record in the state to identify those that have become eligible to be expunged. Then it sends a list of the cases to be sealed each month to the county courts where the charges were brought. The department also does this for some arrest records.

Starting in July, that program will begin to flag newly eligible felony convictions.

Prosecutors and police associations have been vocally opposed, saying in 2022 that it would pose public safety risks.

Jonathan Raven, assistant CEO of the California District Attorneys Association, said prosecutors’ offices have complained they sometimes aren’t given information about automatically expunged misdemeanors when looking up someone’s record. He did not cite specific examples, but said district attorneys don’t always have the resources to double-check the list of automatically sealed cases each month to ensure those defendants are not facing current charges.

“It’s a challenge to have to go through the list and review cases after the fact,” he said.

A spokesperson said the justice department hasn’t received reports from law enforcement agencies unable to view expunged records.

Hough said administrative problems remain for defendants. Some aren’t getting notified their old cases were sealed, he said, while some cases identified by the state haven’t been fully sealed by county courts.

It’s also not yet clear what effect automatic expungement will have on ex-offenders’ employment rates.

Shawn Bushway, an economist and criminologist at RAND Corp. who has studied the issue, is skeptical. He said while there’s no doubt qualified job applicants face discrimination for having prior convictions, requiring a judge’s approval for an expungement sends employers a “reliable signal” that someone has proven their rehabilitation.

He pointed to research conducted after some states passed “Ban the Box” laws blocking employers from asking applicants upfront whether they have criminal convictions, that showed businesses instead discriminated on the basis of race.

With default expungements, “employers will start to realize that there’s a lot of people in their pool with no records that actually have records,” Bushway said. “They could potentially start to discriminate on other grounds.”

The same studies also showed those laws increased the chances that applicants with records get called back for interviews. California has had such a law since 2018. And a recent tight labor market has made some employers more open to hiring ex-offenders.

Employers’ groups such as the California Chamber of Commerce and the National Federation of Independent Businesses have in recent years steered clear of debating expungements. Neither took a position on the new law before it was passed. The federation declined to comment for this story.

Ashley Hoffman, the chamber’s senior policy advocate, said businesses are more concerned about a 2021 California appellate court decision that limits the ways private background check companies can search court records. But some employers under state or federal regulations on who can be hired, including those in the financial and healthcare sectors, are concerned about increasing expungements, Hoffman said.

“We have concerns about some of the movement that is really trying to get to a world where background checks for employees don’t exist or can’t exist,” she said.

At the Sacramento expungement event, Tüzer fielded a series of “what if” questions from a crowd of hopeful potential applicants.

No, the law wouldn’t seal convictions in other states. Yes, it could help them get security clearances to visit family members in state prisons.

Some occupational licensing boards may still be able to see the convictions, Tüzer said, but she advised the crowd to request expungement anyway, reasoning it would look favorable on future applications.

She encouraged them to gather documents for a judge: their own letter outlining how they’ve changed since their crimes; supporting testimony from family, community members and employers; and evidence they’d worked, taken classes or earned degrees since going to prison.

The Anti-Recidivism Coalition said it hasn’t yet had an expungement request be denied, but they have taken anywhere from three months to more than a year to be granted. For violent convictions, judges usually require a hearing or take longer to make a decision, she said.

“I think there is a public hesitancy to see these types of crimes expunged,” Tüzer said. “I think there’s not a whole lot of understanding of what it truly takes for a person who was convicted of a life sentence to come out and reintegrate and how difficult that is.”

Prosecutors have opposed some petitions, but Tüzer said that’s been rare so far. The Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office told CalMatters it doesn’t have a policy on when to oppose petitions, and doesn’t track how many its prosecutors have filed.

For cases where judges hesitate, the coalition returns to a second hearing with further evidence of rehabilitation. That’s what they did for Anthony R., who was granted a felony expungement by a Los Angeles County judge last week, according to a court order he shared with CalMatters.

Anthony, who asked to be identified by his first name to protect his future job prospects, said after coming home from prison in 2016 he struggled to find an apartment and could no longer land the computer programming jobs he used to work. Though he found jobs in homeless services or counseling other ex-offenders, the pay is much lower.

“Anything white collar, I wasn’t going to get,” he said.

After a judge was hesitant to grant an expungement earlier this year, he said he supplied more documentation of ways he’s tried to improve his life, including a coding course he had recently taken. He hopes to work in his former field one day.

Getting the case sealed, he said, made him feel like a different person.

“I feel like I’m a part of society again,” he said.