The State Board of Education is moving forward with plans to add the state’s science assessment to the California School Dashboard, making it a new piece of the statewide school accountability system.

Students first took the online science test in 2019, before Covid forced an interruption of testing in 2020. Starting in 2025, performances by district, school and student groups will receive one of five dashboard colors, designating the lowest (red) to the highest performance (blue) — just as with math, English language arts and other achievement indicators. Each color reflects two factors: how well students performed in the latest year and how much the score improved or declined from the previous year.

Science teachers welcomed the move as a way of drawing more attention to science instruction. “Doing so will add visibility to ensure that districts invest in making sure that all California students receive the science ed they deserve,” Peter A’Hearn, a past president of the California Association of Science Educators, told the state board at a hearing March 6.

“Our biggest frustration is that students have not been getting any or minimal instruction in elementary schools, especially in low-performing and low-socioeconomic schools,” A’Hearn said.

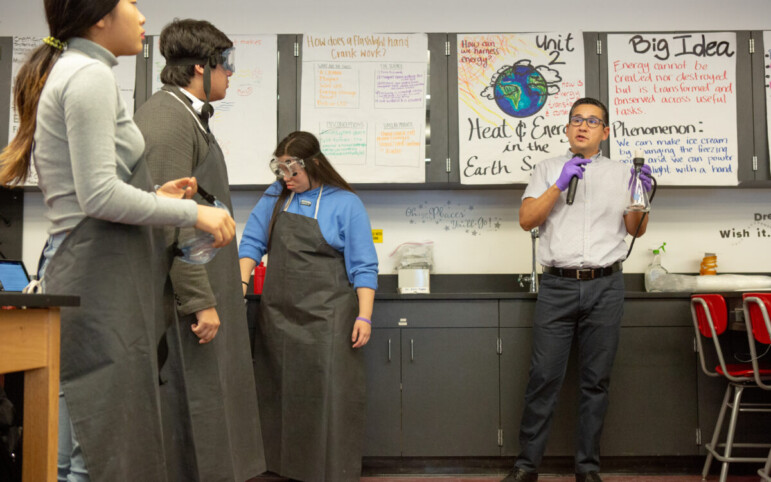

As required by Congress, all students in grades five, eight and at least once in high school take the California Science Test or CAST. Designed with the assistance of California science teachers to align with the Next Generation Science Standards, the test includes multiple-choice questions, short-answer responses and a performance task requiring students to solve a problem by demonstrating scientific reasoning.

For the 2022-23 year, only 30% of students overall scored at or above grade standard. Eleventh-grade students did best, with 31.7% meeting or exceeding standard.

The test measures knowledge in three domains: life sciences, focusing on structures and processes in living things, including heredity and biological evolution; physical sciences, focusing on matter and its interactions, motion, energy and waves; and Earth and space sciences, focusing on Earth’s place in the universe and the Earth’s systems.

California replaced its science standards with the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) in 2013. NGSS was a national science initiative that stressed hands-on learning, broad scientific concepts and interdisciplinary relationships of various science domains. The state board adopted the state’s NGSS framework in 2016, and textbook and curriculum adoption followed.

Districts’ implementation has been slow, with no funding specifically dedicated to teacher training and textbook purchases. The pandemic set back momentum, said Jessica Sawko, director of the California STEM Network, a project of the nonprofit advocacy organization Children Now.

“NGSS pointed us to a higher-quality and richer approach, but it has not yielded statewide equitable access to science,” she said. “There have been shifts in instruction, but they have not been widespread and haven’t resolved a narrowing of access to science, particularly before fifth grade.” She said many districts don’t include goals for science education in their three-year planning document, the Local Control and Accountability Plan. Tracy Unified, which budgeted $768,000 this year for teacher training in NGSS and STEM studies, is an example of one that did (see page 28 of its LCAP).

Although the science assessment will be part of the state dashboard, the State Board of Education has yet to decide how it will factor into the state and federal accountability systems — if at all.

Congress does not require the science test to be included with math, English language arts and graduation rates. Folding the science test into the state system would entitle the lowest-performing districts and student groups to assistance in science instruction from their county office of education.

Student growth measure, too

Also at the March 6 meeting, the state board discussed a timetable for adopting a system to measure individual students’ growth on standardized test scores — an idea that has been discussed for nearly a decade. More than 40 states are using a student growth model for diagnosing test scores.

The state’s current system, which the California School Dashboard reflects, compares the percentage of students who achieved at grade level in the current year with the previous year’s students’ level of achievement. The student growth model, a more refined measure, looks at all students’ individual gains and losses in scale points over time.

A comparison of the two ways of measuring scores was a factor that led to the settlement last month of the Cayla J. v. the State of California lawsuit. Brought on behalf of students in Oakland and Los Angeles, one of its claims was that Black, Latino and low-income children’s test scores fell disproportionately behind other student groups during the pandemic.

The state, using the current method, said that all student groups’ scores fell about the same percentage from meeting standards. Harvard University education professor Andrew Ho’s analysis for the plaintiffs showed that “racial inequality increased in almost all subjects and grades. Economic inequality also increased.” The settlement calls for using scale scores under a student growth model to determine which groups of students will be eligible for state improvement money.

The state must collect three years of data for a student growth model, which it won’t have until next year. Then the state board must decide whether to use it as a replacement or as a complement to the current system for the state accountability system, said Rob Manwaring, a senior adviser for Children Now.