In summary

Schools that banned phones a few years ago have advice for other districts as the governor calls for a crackdown.

At Bullard High School in Fresno, it’s easy to see the benefits of banning students’ cellphones. Bullying is down and socialization is up, principal Armen Torigian said.

Enforcing the smartphone restrictions? That’s been harder.

Instead of putting their devices in magnetically locked pouches, like they’re supposed to, some kids will stick something else in there instead, like a disused old phone, a calculator, a glue bottle or just the phone case. Others attack the pouch, pulling at stitches, cutting the bottom, or defacing it so it looks closed when it’s really open. Most students comply, but those who don’t create disproportionate chaos.

“You should see how bad it is,” Torigian said. “It’s great to say no phones, but I don’t think people realize the addiction of the phones and what students will go to to tell you ‘No, you’re not taking my phone.’”

Bullard, which began restricting phones two years ago, is a step ahead of other schools around the state that have moved recently to prohibit cellphones in classrooms. Bullard and other pioneering schools offer a preview of how such bans might play out as they become more common. Educators who have enacted the smartphone restrictions said they help bolster student participation and reduce bullying but also raise challenges, like how to effectively keep phones locked up against determined students and how to identify and treat kids truly addicted to their devices.

Citing Bullard as an example, Gov. Gavin Newsom last week urged school districts statewide to “act now” and adopt similar restrictions on smartphone use, reminding them that a 2019 law gives them the authority to do so. Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district, recently approved plans to ban phones in January. One bill before the state Legislature would impose similar limits statewide while another would ban the use of social media at school. Another would prevent social media companies from sending notifications during school hours as part of a broader set of regulations intended to disrupt social media addiction.

Calls to limit how students use smartphones are driven in part by concerned educators. A Pew Research Center survey released in June found that 1 in 3 middle school teachers and nearly 3 in 4 high school teachers call smartphones a major problem. During school hours in a single day, the average student receives 60 notifications and spends 43 minutes — roughly the length of a classroom period — on their phone, according to a 2023 study by Common Sense Media.

There is growing pressure to protect young people from excessive screen time generally:

- In June, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy urged Congress to require social media companies to place warning labels on their content in order to protect young people

- Attorneys general from 45 U.S. states filed lawsuits against Meta for failing to protect children

- Released in March, the popular book The Anxious Generation correlates declining mental health among young people with smartphone adoption and encourages parents to demand school districts ban smartphones until high school

The moves to limit smartphone use in California put it near the forefront of an increasingly national trend. In New York, Gov. Kathy Hochul has reportedly been mulling a statewide school smartphone ban for several months now. Florida, Ohio, and Indiana have all imposed some degree of statewide restrictions on phones in schools, and several other states have introduced similar legislation. Education Week in June said 11 states either restrict or encourage school districts to restrict student phone use.

In San Bernardino, ban leads to higher teacher satisfaction

Teachers have had classroom phone policies for years; what’s new at schools like Bullard are that their bans are blanket, campus-wide restrictions. Many of the schools that moved early to adopt such bans are smaller and charter schools, like Soar Academy, a TK-8 charter school with 430 mostly low-income students in San Bernardino. Like Bullard, it also found enforcement of its ban was tough. Suspending students wasn’t an option. Neither was yanking phones from students’ hands. That left an honor system, which relied on students’ willingness to accept that smartphones and social media are harmful to their mental health and a distraction from learning.

“The key was that we needed 100% buy-in from teachers. There couldn’t be a weak link,” said Soar principal Trisha Lancaster. “It was scary, because we weren’t sure it was going to work. But we were determined to try.”

Lancaster said it also helped not to give parents or students a choice in the matter. The school simply presented the new policy, alongside ample research on the harmful effects of cellphones and social media on young people, and made it clear what the punishments would be.

For the first violation, staff would keep a student’s phone for the day and call their parents. Punishments would escalate until the sixth offense, when a student would have to meet with the school board, whose members might suggest the student enroll elsewhere.

“It was scary, because we weren’t sure it was going to work. But we were determined to try.”

Trisha Lancaster, principal, soar academy in san bernardino

At Soar, the idea originated at the end of the 2022-23 school year, when teachers said they were fed up with distracted students and an overall dispiriting school climate. Students, Lancaster said, “had lost their social skills.”

So the staff decided to ban phones during class, at recess, at lunch and after school — essentially, all times except when in a special area where parents or others can pick them up from school. Students must keep phones off and in backpacks when they are not permitted.

The first year of the ban went smoother than expected, Lancaster said. Some students and parents protested, but most understood the policy was in students’ best interests. Test scores didn’t budge much, but at the end of the school year, a survey of teachers showed much higher job satisfaction than they recorded previously. And walking across campus, the improvements are obvious, Lancaster said.

“Everyone on campus is so much happier. You see kids actually socializing, problem solving, enjoying themselves,” Lancaster said, choking up as she described the school atmosphere. “It’s true, it’s one more thing to enforce. But education matters, and now kids are learning. That’s the No. 1 reason we did this.”

Bans from San Mateo to San Diego

Soar’s experience has been mirrored on a larger scale in the San Mateo-Foster City School District, which serves 10,000 students at 21 TK-8 schools south of San Francisco. After a full-time return to campus in 2022, teachers in the district found many students were “interacting intensely with cellphones in a way we didn’t see before the pandemic,” said superintendent Diego Ochoa, and so the school district adopted a smartphone ban for four middle schools in 2022.

Administrators were convinced to do so following a trip to a nearby high school with a smartphone ban. There, they saw students speaking to each other and looking at one another during break time instead of their phones.

Ochoa said the benefits of locking smartphones away is evident from improved test scores and an anonymous annual student survey that found a decline in depression, bullying, and fights in the 2023-24 school year relative to prior years. But saying the smartphone ban led to those benefits is tricky because they could have also been caused by other policy changes that happened at the same time, including a ”restorative” approach to discipline that relied less on detention and suspension and more on support from counselors. Still, when students were surveyed specifically about the policy and the biggest difference in their education since it was put into place, they said that they pay more attention in class.

Ron Dyste also implemented a smartphone ban and, like Ochoa, recommends them. Dyste is principal at Urban Discovery Academy, a TK-12 charter school in San Diego, which banned cellphones during the 2023-24 academic year amid an uptick in bullying, harassment and anxiety among students, staff told CalMatters. Nearly 90% of discipline cases, across Urban Discovery Academy and a school where he worked previously, could be traced to misuse of phones or social media, including students filming fights, spreading nude photos of classmates and encouraging students to kill themselves.

“I may never get some of those images out of my head. It’s horrible, what kids can do to each other,” Dyste said. “The damage to our kids and our communities is real.”

Dyste got the idea to ban phones when he and his wife went to a Dave Chapelle performance where audience members were required to secure their phones in locked pouches.

“My wife said, why don’t we do this in schools?” he said. “We knew we had to do something.”

Over last summer, the school sent out notices to families about the new policy, explaining the rationale. Some students complained, but parents were thrilled, Dyste said. And the improvements in campus climate were almost immediate.

“The damage to our kids and our communities is real.”

Ron Dyste, principal, Urban Discovery Academy in san diego

Instead of “hiding away with their screens,” said Jenni Owen, the school’s chief operations officer, students spent their breaks talking, dancing, playing volleyball, and having fun. They developed empathy and a sense of community, she said.

At the end of the academic year, the school logged zero fights. The previous year, the school’s suspension rate was 13.5%, almost four times the state average.

“For schools that are wondering if they should take this on, I think the answer is, we have to,” Dyste said. “If we don’t educate kids on how and when to use this technology, we’re going to continue seeing a rise in suicide, sexual harassment, and anxiety.”

State legislators have recognized the importance of healthier technology use among children. California students are supposed to learn about “appropriate, responsible, and healthy behavior… related to current technology” under a media literacy law passed in October.

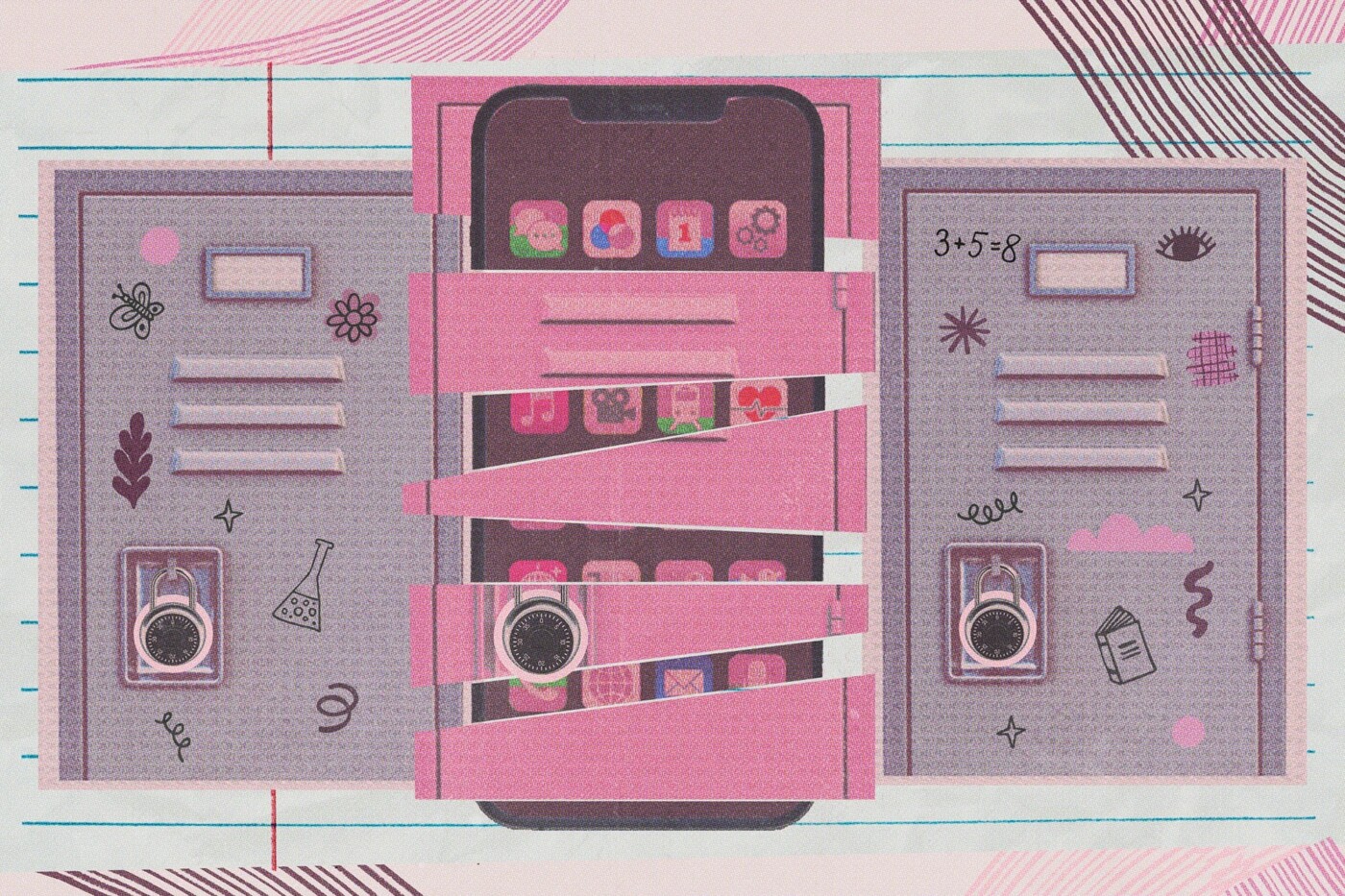

To pouch or not to pouch

To enforce smartphone bans, some schools rely on smartphone lockers or locked pouches like the kind Dyste saw in use at the Dave Chappelle show.

He tried using locked pouches from the Los Angeles-based company Yondr but encountered numerous issues. Some kids were breaking and smashing the pouches to open them, or they’d listen to music all day by connecting their earbuds to their locked-away phones using Bluetooth.

“We had to return what was left of the equipment,” he said. Instead of going with Yondr, which wanted $6,000 to cover 110 kids, Dyste found clear, plastic phone lockers on Amazon that cost $50 each and put one in each classroom.

Yondr told CalMatters: “Our pouches are designed to withstand heavy-duty usage, and we are continuously working to improve the durability of our solution. However, there will always be students who try to push boundaries, especially when policies are initially rolled out. For this reason, it is critical that our team works directly with districts and administrators in rolling out the Yondr Program, to ensure that the most effective policies and procedures are implemented for successful school-wide adoption. Without adherence to strong policies, schools may struggle with student compliance.”

Soar Academy also considered purchasing Yondr phone pouches but was discouraged by the $19,000 price tag.

The San Mateo-Foster City School District paid $50,000 to obtain Yondr pouches for roughly 3,000 students. To use them, staff hand out pouches at school entryways each morning, then students swab the pouch over a demagnetizer to unlock the pouch at the end of the day. Kids who want an exception to the rule — for a family emergency for example — must come to the school front office and ask for permission.

Yondr pouches come with a hefty price tag, Ochoa said, but he thinks it’s worth it to improve student focus.

“Call up five random superintendents, I don’t care where they’re at and ask them, how much would you spend to have your students pay more attention? It’s worth millions,” he said.

Mixed feelings among students

Whether phones get locked in a clear box or a silver pouch, Oakland High School senior Leah West said she finds it punitive to require students to lock their phones away before they have broken any rules with the devices. While Oakland High School does not have a blanket smartphone ban, her former English teacher sometimes locked student phones in Yondr pouches.

“We should be given a chance to prove ourselves,” she said, adding that such an approach can motivate a rebellious streak in students like her who like freedom and don’t like when she isn’t trusted to make a responsible decision.

Louisa Perry-Picciotto, who graduated from high school in Alameda in June, said students with jobs rely on their phones for work updates and all teens use their phones to communicate with their friends.

Still, she’s grateful her parents didn’t get her a smartphone until she was in eighth grade.

“I get distracted easily, and without a phone I was a lot more connected to the world,” she said.

Edamevoh Ajayi, who is a junior at Oakland Technical High School, said there’s no question some students don’t pay attention in class because they’re busy texting or playing games. Those students would definitely benefit from rules surrounding cellphone use like the kind being implemented at her school this year.

But she feels like she has a strong sense of self-control and a desire to learn, and doesn’t need a phone ban.

“When they take away my belongings, I feel like I’m being treated like a child,” she said. At her school, policies vary by classroom. In general, students are free to use their phones between classes and at lunch.

When students use their phones in class it can be frustrating for everyone else, said Fremont High School science teacher Chris Jackson. It puts teachers in a tough position: Either ignore that student and carry on for the sake of the students who are listening or disrupt learning for all students and confront them.

In the long run, Jackson said he’s worried that Black and brown students, who have historically faced higher rates of punishment than other students, will again bear the brunt of disciplinary actions related to smartphone bans. Rather than punishment, Jackson would prefer to see solutions that address root issues like addiction that lead students to use their devices in violation of the rules. So no matter what policy school districts adopt, he wants the focus to remain on teaching students digital literacy and how social media can be a risk to their health.

Course corrections

Some schools who helped pioneer smartphone bans have reassessed their initial approach.

This year, Bullard is changing its policy to allow students to access their smartphones at lunch time. Torigian said school administrators wanted to make room for important communications, for example by allowing students who pick up younger siblings to text with their parents. They also hoped the looser rules would encourage more students to comply with the ban.

If kids don’t comply, teachers call parents, and if they still refuse they’re sent to what the school calls the re-engagement center. Starting last month, California began prohibiting suspensions for “willful defiance.” Torigian believes that schools need an exemption from the policy in order to enforce smartphone restrictions. He wants it back because he said he needs a way to hold kids accountable.

“That’s why the governor’s got to give us some leeway on this willful defiance; you can’t do one [smartphone restrictions] without the other.”

“Our teenagers told us, ‘you forgot to explain why we’re doing this.’”

Diego Ochoa, superintendent, San Mateo-Foster City School District

Ochoa said if he had to do it over again in San Mateo-Foster City he would devote more time to explaining to students why they adopted such a policy before putting it into place. Getting a smartphone is a big deal for middle school students, a milestone for adolescents that represents more freedom and autonomy, and it’s counterproductive for the school environment if they feel punished or something they value is taken away with little explanation.

“Our teenagers told us, ‘you forgot to explain why we’re doing this,’” he said, adding that even if a small percentage of kids violate the policy it can be really harmful academically and to school culture. “Even with your conviction to implement a policy like this, spend the time developing the language around the policy and explaining it to your students.”

Common Sense Media CEO Jim Steyer, whose nonprofit is focused on how children use media and technology, agreed that it works best to explain to kids why a rule to limit smartphone access at school is necessary. Parents and teachers need the same explanation so that they can help enforce some restrictions in order to keep kids safe and healthy.

“Any even remotely engaged parent is going to want their kid to do well in school, and is going to want them to understand why phones and social media platforms get in the way of learning and can be really distracting and can affect your mental health,” he said.