For most K-12 student groups in California, test scores have been maddeningly flat since the pandemic. But for Black students, stagnant scores have been particularly frustrating: Black students’ math and English language arts scores inched downward for most grade levels last year, notching some of the lowest scores among any student group.

At least one district, however, has reversed that trend. Emery Unified, a small district tucked between Berkeley and Oakland in the east Bay Area, saw its Black students — who make up 45% of the student population, one of the highest rates in the state — show dramatic gains from 2022. Math scores nearly doubled over last year and English language arts scores far surpassed pre-pandemic results. Chronic absenteeism dropped 8.4 percentage points, far more than the state average.

“I saw those scores and I was elated,” said Jessica Goode, principal of Emery High School. “All the work we’ve done has paid off. It’s been a challenge — there’s no road map because almost no one’s ever done this successfully.”

Emery Unified’s scores are still far below average, but they’re trending upward at a time when scores statewide are unchanged or slipping backward. The number of Black students meeting or exceeding the state English language arts standards jumped more than 12 percentage points last year, from 24% to 37%, and the math scores climbed from 9% to 15%. Statewide, Emery’s Black students outperformed their peers by a wide margin in English, and crept close to the state average for Black students in math.

Even though the scores are relatively low, the turnaround is worth celebrating, said Tyrone Howard, an education professor at UCLA.

“I see these pockets of hope, these glimmers of possibility, and think, how can we replicate this?” Howard said. “Emery Unified is on my radar, and it’s important to find out what’s happening there.”

Black students have long trailed other groups academically, Howard said, because they tend to attend schools with less experienced teachers, and are more likely to be homeless, in foster care or living in poverty — all factors that can hinder a student’s ability to focus in class.

Howard said racism plays a role, as well.

“Low expectations and a lack of resources for Black students plays just as much a factor as anything else,” Howard said.

For years, some advocates said California’s method of funding schools left many Black students without the additional resources they need. Through the Local Control Funding Formula, the state gives extra money to districts based on student poverty levels and other criteria, not based specifically on students’ race or ethnicity or the needs at individual schools. To address this, Gov. Gavin Newsom last year added a provision to the formula known as the equity multiplier, which allotts more money to districts based on student turnover and high rates of low-income students at specific school sites. The change doubles the percentage of Black students who will receive extra funding, according to Catalyst California, an education advocacy group.

Black teachers also play a big role in Black students’ success, research has shown. Emery Unified has long prioritized hiring Black teachers, far outpacing the state average. More than 30% of Emery Unified’s teachers are Black, compared to just 3.9% statewide.

According to a 2018 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research, Black students who had at least one Black teacher in the early grades were 13% more likely to graduate and 19% more likely go to college than their Black classmates who didn’t have a Black teacher. Black teachers also tend to have higher expectations for their Black students, and are less likely to view them as disruptive or inattentive, studies show.

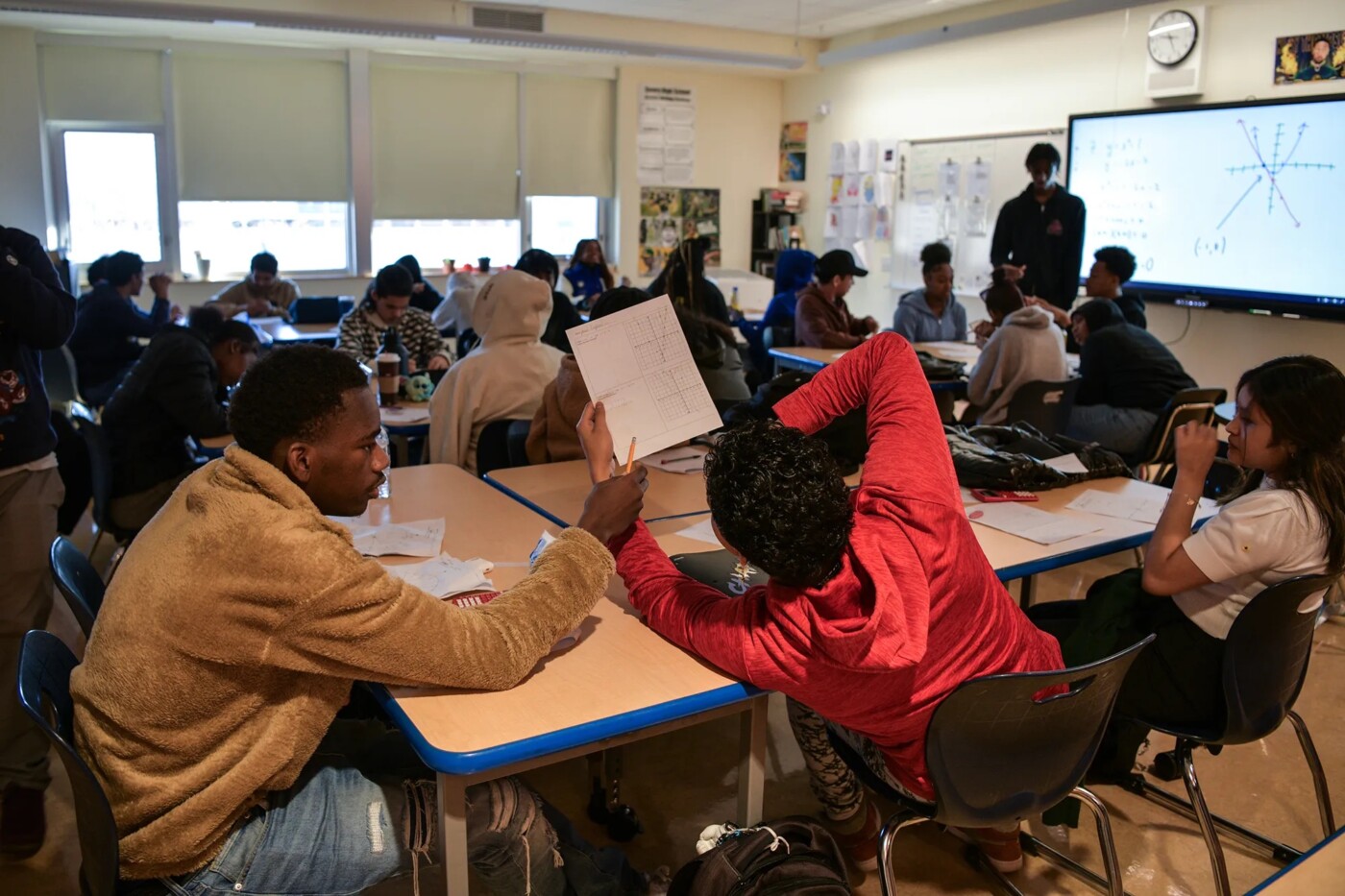

Efforts to turn things around at Emery High began long before the pandemic. Goode and her staff started meeting regularly to look closely at student performance data and curriculum, giving extra attention to students who were struggling.

The school also shifted to a “grading for equity” system, which focuses more on assessing students’ knowledge at the end of the grading period rather than their classroom behavior or whether they turned homework in on time. The new system helped motivate students and gave teachers a better idea of how students were progressing, Goode said.

Another tactic that’s helped: paying teachers extra money to stay after school and tutor students. The school also started taking students on college tours around California, bolstering its skilled trades program and expanding its mental health resources.

“I hated school so much when I was a teenager,” Goode said. “That’s always been my goal here: I don’t want these students to hate school. I want them to have options, both in school and after they graduate.”

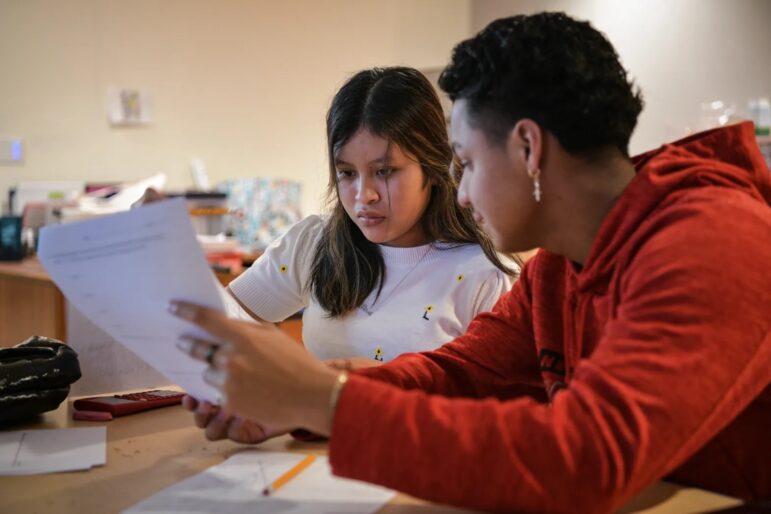

Jesus Herrera, a math teacher at Emery High, credited the surge in math scores to his close collaboration with the school’s other math teacher. The two started meeting daily to align their lesson plans and set consistent, higher standards, ensuring smooth transitions from algebra to geometry and beyond.

Seeing the improvements has been gratifying, Herrera said.

“I like teaching, and this shows we’re doing a good job,” Herrera said.

Jordan King, a junior at Emery High who is Black, said he appreciates the small, close-knit campus culture, and that most of his teachers are Black or Latino.

“There’s so many people of color in leadership roles. They understand what students go through, the struggles,” King said. “They’re not biased when they teach history, for example. And they’re nice people in general.”

King, who’s on the school’s debate and track teams, hopes to go to college after he graduates. As the student representative on the school board, he’s considering pursuing politics, law or history.

He credits his teachers with inspiring him to excel.

“I definitely push myself more than I used to. I go to tutoring all the time, missing track or debate if I have to,” King said. “I want to make my family proud, let them know they raised a scholar, a good kid who’s going to achieve things.”

At the elementary school, principal Samantha Burke credits three initiatives for the turnaround in test scores and chronic absenteeism. The first is a focus on writing skills, starting before students can even read. In kindergarten, students “write” stories by drawing pictures, gradually adding words and short sentences, to develop story-telling skills. In older grades, students practice a variety of writing styles, such as opinion pieces, fictional narratives and expository pieces, with increasing complexity.

For example, an assignment for third-, fourth- or fifth-graders might be to write a multi-paragraph story about a celebration, followed by instructions to add plot twists, suspense and a surprise ending. Burke and her staff came up with the idea because they noticed that during remote learning, students were reading a bit, but doing very little writing because teachers weren’t able to offer individual guidance.

“We found that focusing on writing has helped students with reading, too,” Burke said. “They learn spelling, vocabulary, grammar, patterns. It’s had so many benefits.”

Elementary English language arts scores jumped 5 percentage points, from 33% meeting or exceeding the standard in 2022 to 38% last year.

Another change focused on accountability. Teachers started showing students their standardized test scores, and Burke met with each student individually to discuss the results and set goals. Students who scored at or above grade level standards were honored with awards and celebrations.

“It was highly time consuming but it created higher expectations. Students understand they need to do the best you can,” Burke said. “You could see a shift. Students started taking school more seriously.”

The third initiative focused on attendance. The school hired an attendance clerk to follow up with families who struggled to get their kids to school. School officials also planned regular events “to make school more fun,” such as pool parties, ice cream days, dance and capoeira martial arts classes and family nights with bingo and movies.

Chronic absenteeism was still high last year — 33% — but declined more than 8 percentage points from the previous year.

“When I saw our scores, there was a sense of relief,” Burke said. “These practices we’re building, they’re not for naught. We’re on the right track. Now we have to continue moving the needle.”