One of the Bay Area’s newest museums is hidden among the trees on Angel Island State Park. It tells a story of immigration to the Pacific Coast, with particular emphasis on the Asian experience.

The Angel Island Immigration Museum opened in January. It is located inside a former U.S. Public Service hospital built over 100 years ago, where Asian patients were segregated from Europeans.

The 10,000-square-foot museum is part of the 15-acre Immigration Station, which operated on the island between 1910 to 1940, in the northeast corner of the island.

An estimated half million immigrants passed through the Immigration Station during that time frame, with more than half coming from China or Japan. Chinese immigrants were discouraged from coming to the United States under a series of restrictive immigration laws, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

About 20% of the Chinese immigrants on Angel Island were deported, according to Edward Tepporn, executive director of Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation and an Asian immigrant himself.

These sobering facts are the focus inside a bright, airy yellow two-story building, which was renovated at a cost of $15 million, after sitting vacant since World War II. Funding came from a variety of federal, state and private sources, Tepporn said.

One of the most striking features of the new museum is not its initial exhibits, but the new entry doors, which are labeled “European” and “Non-European,” to remind visitors of the immigration center’s segregated past.

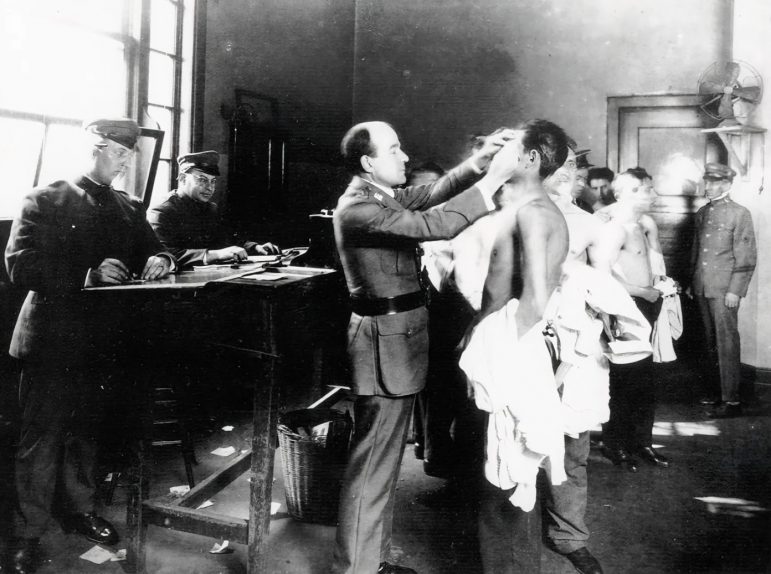

The doors, said Tepporn “weren’t actually labeled as such, but they functioned as such. Part of it was at the time the stereotypes about Asians were that they had dirty habits and they carried diseases,” he said. “And so they wanted to segregate the Asians from the non-Asians, from the Europeans.”

Asians and non-Asians were segregated throughout the entire immigration station, in the detention barracks and dining halls, and when the hospital opened in 1910, there were separate stairwells and separate entrances. But doctors complained that the hospital setup impeded the flow of patients, and it was changed, Tepporn said.

Inside the new Immigration Museum, some old doors and one room were kept intact. Parts of the second floor that were used by doctors 100 years ago now display exhibits about medical treatments in the renovated structure.

Other exhibits focus on the contributions that immigrants have made to the U.S., as well as the historic and contemporary experiences of detention and exclusion. Several rooms of the restored building are still empty.

The entire Immigration Station area is a work in progress. Many of the buildings around the new museum are boarded up, some with collapsed roofs. Since 1983, visitors have been able to tour the adjacent Detention Barracks Museum, which housed waiting immigrants. Inside, museumgoers can see 200 poems carved into the wooden walls by the immigrants. Outside, there are several historical displays.

Due to COVID concerns, the Angel Island Immigration Museum initially opened with a virtual ribbon-cutting ceremony.

“The hope is at some point we’ll be able to have a proper grand opening for the museum,” Tepporn said. “It’s probably not going to happen until spring or summer of 2023.”

On a recent sunny Saturday afternoon, when Angel Island was teeming with day trippers, only four visitors were at the new museum. A tour group of 15 had visited earlier in the day, Tepporn said.

“We want everyone to visit,” Tepporn said. “Truly it should be a site that is meaningful for everyone, regardless of where you were born or how you identify. Because it’s an important chapter of what happened here in the U.S., that’s important for everyone, and to remember and to think about how we treat newcomers and immigrants to the U.S., then and now.”

Visiting the Museum

The Angel Island Immigration Museum is currently open weekends from 11 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Admission is free, and it is designed for self-guided tours.

Visitors to Angel Island have several options for accessing the Angel Island Immigration Museum. They can walk 1.2 miles from the ferry station. Bicycles can be rented or brought on the ferries that serve the 740-acre island. Bikes need to be locked outside the immigration station’s fenced area, and cyclists then walk the last 1,000 feet to the museum. Information about taking a tram directly from the ferry to the new museum is available at https://www.angelisland.com/ or by calling (415) 435-3392. Tram tickets cost $11.

Virtual tours of the museum exhibits are available by visiting https://www.aiisf.org/aiimexhibit.

The adjacent Detention Barracks Museum is open Wednesday through Sunday, and admission is $3-$7. Children under 4 get in for free.