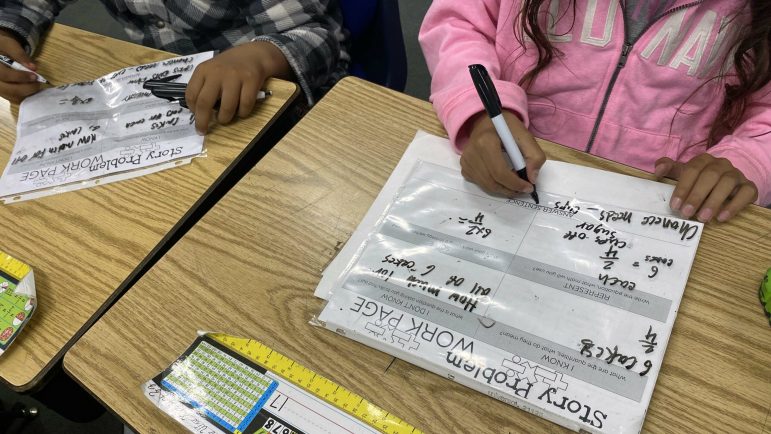

When Nicole Thompson teaches a math word problem to her fourth grade class in Pajaro Valley Unified, she has the class read it over three times.

After the first read, students discuss with a partner what the situation is that’s described in the word problem. The second time, they discuss what numbers they see and what those numbers mean. The third time, they talk about the question and what they need to solve.

Thompson said the strategy really helps her students, especially those for whom English is a second language.

“This really enhances the comprehension part of it,” said Thompson. “Our story problems are paragraphs long and the students can feel really bogged down when they’re looking at their math page.”

Thompson learned this strategy during a series of trainings on improving math instruction for multilingual learners, a term that refers to all students who speak a language other than English at home. The trainings were organized by the nonprofit organization TNTP, formerly known as The New Teacher Project and Stanford University’s center for Understanding Language, which is focused on improving instruction and assessment of English learners and other students. TNTP offered the training program in 2021 to teachers in Pajaro Valley Unified in Santa Cruz County, West Contra Costa Unified in the Bay Area and Aspire Public Schools in the Central Valley.

“We know from our work that multilingual learners do not have the same access to grade-level assignments as their peers,” said Jeanine Harvey, director of multilingual learner academics at TNTP.

“We wanted to show teachers that all students could engage with grade-level assignments with the right supports.”

Jeff Zwiers is a senior researcher at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and the director of professional development for the Understanding Language initiative. He said it’s important for students learning English to talk with each other a lot about what they’re learning, and ask questions like, “What do you mean by that? Why did you do that? Where in the problem does it say that? What’s an example of a ratio in real life?” These questions require deeper discussion of ideas, and more language, giving students a chance both to practice using language to describe ideas and to listen to how others speak – vocabulary, syntax and organizing sentences.

“They’ll hear some from the teacher. But if they’re face to face with another person, there’s a lot more attention, there’s a lot more focus,” Zwiers said. “Very few kids will raise their hand and say ‘Can you explain that?’ to the teacher, particularly multilingual learners, who need it the most, they won’t do that. But with one other person, it’s a safer setting.”

In addition to teaching strategies for supporting more student discussion in the classroom, TNTP staff worked with teachers to analyze word problems from their district’s math curriculum, identify what vocabulary students would need to understand in order to grasp the problem, and design graphics or word definitions to help their students.

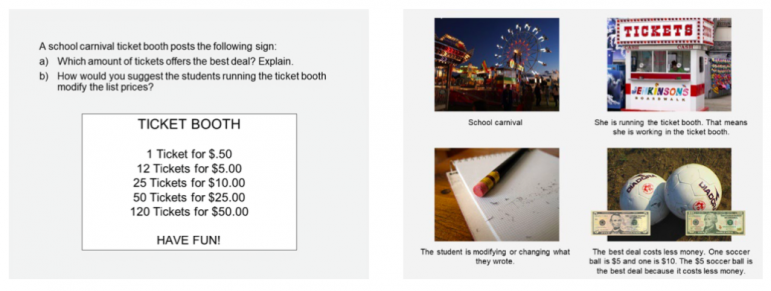

For example, one math problem showed a school carnival ticket booth sign with prices for different quantities of tickets, and asked, “Which amount of tickets offers the best deal? How would you suggest the students running the ticket booth modify the list prices?” Teachers found pictures to illustrate the meaning for words or phrases that multilingual learners might not understand, like “modify,” “school carnival,” “best deal” and “running the ticket booth.”

After trying out a strategy in the classroom, TNTP also worked with teachers to reflect on which students participated, how they used language in the classroom, and how they could work to include more students in the next lessons.

According to surveys conducted by TNTP, the training program improved teachers’ confidence. Before the training, only 40% of teachers in Pajaro Valley Unified and West Contra Costa Unified said they felt confident in supporting English learners in their classrooms. Afterward, more than 75% felt confident.

Many teachers also said the training helped them see that their students are capable of hard work.

“Sometimes we forget that students are more capable than we see. These trainings kind of opened my eyes on that. Now I see them as more talkative, more capable of doing their work on their own,” said Juan Gonzalez, who teaches fifth grade in Pajaro Valley Unified.

Gonzalez said he enjoys seeing his students having conversations about math and using more complex vocabulary.

Rebecca Aldrich, who teaches fifth grade at Aspire’s Alexander Twilight College Preparatory Academy in Sacramento, participated in the training sessions held by TNTP in March 2021 and then in yearlong coaching with TNTP staff. She said her students’ scores on i-Ready, a diagnostic assessment of math and English, improved by 178%.

“For me the proof is in the data. I really started seeing students take over their own learning, apply what they were learning,” Aldrich said. She said students started using the same strategies for discussing and solving problems in other classes as well. “They became more collaborative in all areas.”

Suzanne Marks, partner of academics for TNTP, said she was struck by how many teachers did not have access to data about which students were learning English and how far along they were in their progress of learning the language.

“Even for teachers who had access to information, I was struck by how infrequent and cursory their analysis and engagement with that data was. A lot of them talked about getting it at the beginning of the year and that was it,” Marks said.

Thompson said she has seen more students raising their hands to participate out loud in class. She said the strategies have been especially helpful this year, after a year of distance learning.

“My class this year is super, super quiet. They’ll play and laugh and have fun on the playground, but once we come into class, they are a very timid group,” Thompson said. “It was really important to me to give as much time to talk with each other as I can.”

Karlisha Alston, a sixth-grade teacher in Pinole, in West Contra Costa Unified, said she uses some of the strategies she learned in the math trainings in her English language arts classes as well. For example, she has students discuss their answers with each other, compare and contrast how they got their answers, and then revise them.

“I like it because when we start a lesson, sometimes kids are very, like, ‘I don’t know if I’m going to learn this.’ When they do their reworking, it lets them know, ‘You learned something new. It’s OK to continue to learn,’” Alston said.