California has more eligible students for admission to the state’s public universities than those campuses have space for.

A new report released Wednesday by The Campaign for College Opportunity highlights that more eligible students are applying to the University of California and California State University campuses than those colleges can admit. The lack of capacity means that fewer qualified Latino and Black students are applying to these universities.

It also means that the state is still projecting a shortfall of workers with bachelor’s degrees and ranks 34th nationally in awarding four-year degrees.

“It has gotten exceedingly difficult to get into the University of California and a growing number of Cal State campuses,” said Michele Siqueiros, president of the California-based campaign organization, which is focused on improving higher education opportunities for students. “Harder than in previous generations. It’s a real issue of fairness and equity at a time when we know a college degree is valuable and more high schools are preparing for college.”

It’s a problem the legislature and governor’s office also plan to tackle. Assemblyman Kevin McCarty, chair of the Assembly Budget Subcommittee on Education Finance, said expanding access and affordability will be a priority next year.

The UC system did make a commitment several weeks ago to enroll at least 20,000 more students by 2030, but McCarty said he and the legislature will plan to ask each of the universities including CSU for at least 30,000 more.

He also said the California Master Plan for Higher Education, which was never adopted into state law, needs to be updated to reflect the 21st-century economy that requires more bachelor’s degrees. “We need more college degrees to meet the jobs of today and tomorrow,” he said, during a webinar hosted by the Campaign Wednesday about the report. McCarty said the state’s master plan was written in the 1960s and what the economy requires today is very different. “We know you need more education to focus on what you need in this economy and the number of people attending high school in California is declining, but the number of people A-G ready is through the roof.”

A-G requirements are high school courses required for admission to the UC and CSU systems such as science, English, history, algebra and geometry.

One reason for the capacity limitations – state budget cuts in the past. The share of the state budget invested in higher education declined from 18% in the mid-1970s to 11% in 2018-19, where it remains as of the 2021-22 budget, according to the report.

“We’re fortunate we have a governor in Gavin Newsom that understands and made historical investments in the last two years,” Siqueiros said. “But we haven’t done that in the course of the last 20 years, so those historic investments aren’t going to make up for the many years we haven’t made adequate investment.”

McCarty says the legislature and the governor’s office going back to former Gov. Jerry Brown have refocused on higher education, but there’s a lot of ground to make up.

“During 2009, 2010, and 2011 we increased prison spending by $2 billion and cut education and higher education by $2 billion,” he said. “We haven’t recovered from those losses, and we still need to do more.”

The report found that more California high schoolers are eligible to attend a California public university. About half of the state’s high school graduates are completing A-G courses. And more California students are applying for admission to UC and CSU.

The imbalance has long existed in California’s public university systems, but the study emphasizes the need for change.

Eligible high school students are especially impacted and face challenges when they attempt to gain access to their preferred UC or CSU campus or a specific program. And freshman admission is highly competitive to the UC system. The average high school GPA of students admitted to the system has increased and is close to or above a 4.0 at nearly all nine undergraduate campuses, according to the report. For example, at UC Merced, students admitted to the campus have the equivalent of a 3.7 GPA.

Merced is the only UC campus that accepts students from the referral pool, which describes those high-achieving students who are not admitted to their preferred campus. These are students who rank in the top 9% of their graduating high school class and meet UC eligibility. They qualify for the statewide guarantee for UC admission but not necessarily to their top choices. According to the report, nearly 12,000 UC applicants were in the referral pool in 2019. Only 553 of those opted for admission to the Merced campus and only 57 chose to enroll.

“Guaranteed admission to all eligible students is a false guarantee when they’re being directed to a campus where we know 90% of them won’t enroll,” Siqueiros said. “We think it’s especially concerning in regard to CSU because students who apply to CSU are place-bound, maybe older, or have families. If they’re not admitted into an institution in their region, they’re unlikely to go to Humboldt in the north state or a campus far away from home.”

In the CSU, 16 of the 23 campuses have more freshman applicants meeting statewide eligibility requirements than the physical capacity and resources to admit. And nearly all CSU campuses, except Dominguez Hills, have specific programs or majors that are at capacity. For example, more than 60% of business departments are at capacity across the system, especially those with accounting specializations.

Like the UC system, CSU redirects eligible freshmen who may not be admitted to the campus of their choice to a different university. But in 2020, of the more than 7,000 freshmen who were redirected only 117 enrolled.

CSU Chancellor Joseph Castro said, during the webinar, the system is currently working on a strategic plan that would allocate more than 9,000 newly enrolled students next year to the campuses with the most demand like San Diego, San Luis Obispo, Fresno and Bakersfield.

McCarty said increasing slots for students is “just one piece of the puzzle. Another piece is we’re working on housing and college costs. We need more student housing on campuses to deal with the pressure students are currently facing with housing instability.”

McCarty said he’ll propose an additional $5 billion to build “much-needed” housing for UC and CSU. As well as, more investment in financial aid to address non-tuition costs.

The capacity problems mean California ranks near the bottom, at 41st, for public undergraduate enrollment in the four-year sector.

In other states, four-year public universities account for the majority of undergraduate enrollment. But in California, “the vast majority of low-income, Latinx, and Black graduates never attend a four-year university,” according to the report. The state sends qualified bachelor’s degree-seekers to a community college instead.

And because of challenges and barriers to transfer, the state isn’t producing enough bachelor’s degree holders. For example, more than three-quarters of community college students plan to transfer, but only 19% do so within four years.

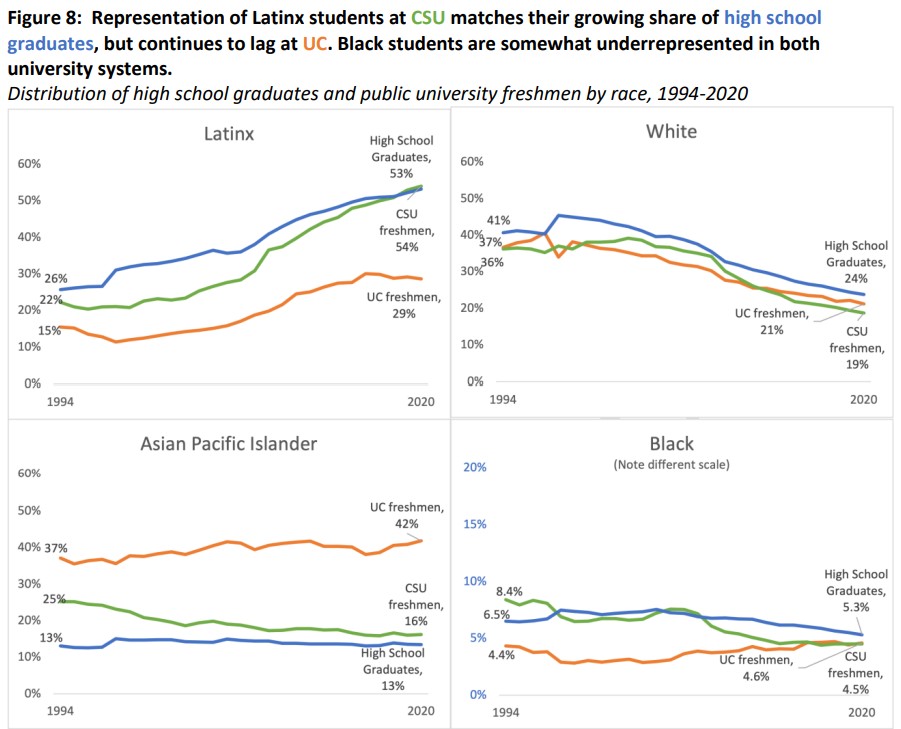

The report also highlights that Black and Latino students are significantly underrepresented in the UC system when their percentage of enrollment is compared to the eligible graduating students in the state. (Only Black students are underrepresented in the CSU.)

The report also found that among eligible Latino high school graduates who had completed A-G courses, less than half applied for admission to the UC.

“UC is celebrating record applications and admissions for Latinx students this year,” Siqueiros said. “But much of that is driven by reality and growth in that demographic.”

Siqueiros said it’s concerning what’s happening to Black and Latino students, that they don’t apply even when they’re qualified.

Black and Latino high school graduates are looking for campuses that give them a sense of belonging, are welcoming and have plenty of faculty and staff who look like them, Siqueiros said.

“For Black students, we’ve seen the real impact that the ban on affirmative action has had on universities’ ability to intentionally recruit and admit,” she said.

Data on high school graduates and their admission shows that the representation of Latinx students at CSU matches their growing share of high school graduates, but representation continues to lag at UC. Black students are somewhat underrepresented in both university systems. At CSU the share of Black freshmen has been dropping steadily from 7.2 percent in 2007 to 4.5 percent in 2020. “California’s Black students are disproportionately likely to start their college careers at a community college,” the report concludes. While white students are “not much more likely than Black students to end up in a California public university,” nearly 1 in 5 white high school graduates go out of state for college, the report said.

Beyond the report, the campaign is also making several recommendations that the public university systems and the state Legislature should undertake to increase access and produce more bachelor’s degrees, including:

- Formally adopting a statewide degree-attainment goal that ensures 60% of adult Californians earn a degree or high-value certificate.

- Revise and expand eligibility requirements in the California Master Plan for Higher Education so graduates from the top 15% of high schools would be eligible for the UC and the top 40% for the CSU.

- Build a five-year plan to increase enrollment at the UC and CSU to meet the statewide degree goal while also closing racial and ethnic gaps in access and completion.

- Establish a higher education coordinating body to set goals, provide oversight and collect data to help advance the state toward the 60% degree-attainment goal.

- Eliminate the use of standardized tests like the SAT or ACT for admission. CSU is considering dropping the exams, and UC has already done so.

Castro said the system’s Board of Trustees will receive a recommendation from an advisory committee in January to drop the SAT and ACT exam for admission. The board will vote on the issue in March.

A five-year strategic plan to address these issues has to be more than a one-time infusion of additional dollars, Siqueiros said.

“Institutions need to be able to plan,” she said. “They can’t hire faculty overnight to teach more courses, they can’t provide adequate and affordable housing overnight or build buildings overnight. How are we going to be strategic and intentional about expanding access and just as intentional and thoughtful about closing persistent inequities?”