In 1972, just 18 days after he was selected to run for vice president with Democratic Sen. George McGovern, Thomas Eagleton was forced off the ticket. The issue? Years earlier, Eagleton had been hospitalized and treated with electroshock therapy for depression. The disclosure of his mental health history was a blow from which the Missouri senator could not recover.

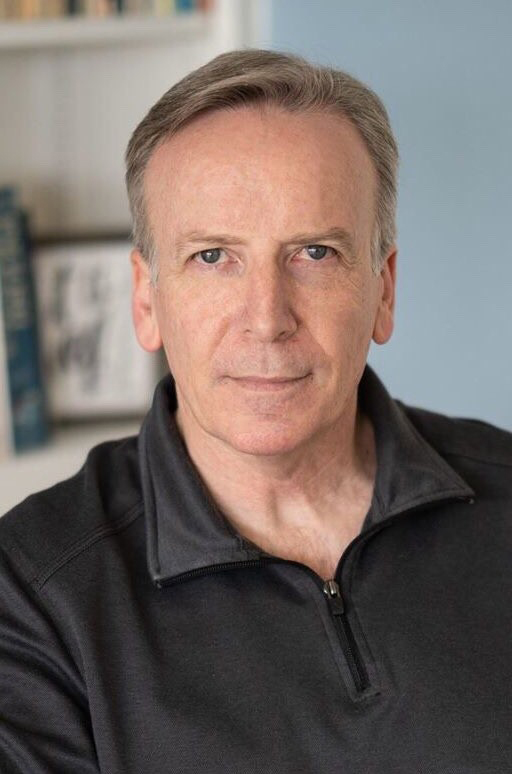

Eagleton’s torpedoed candidacy has been a cautionary tale for elected officials ever since, says California Superior Court Judge Tim Fall, who serves in Yolo County. But rather than remain quiet as he approached his own reelection season last year, Fall came out with a book that detailed his decades-long struggles with anxiety and depression.

As it turned out, Fall was unopposed for another six-year term in office. But it was a previous challenge for his seat, in 2008, that had triggered his most difficult bout with mental illness. That campaign forms the backdrop of “Running for Judge,” which Fall said he wrote to show that struggling with mental illness doesn’t disqualify people from high-pressure professions.

Fall, 61, who has a law degree from the University of California-Davis, was 35 when then-Gov. Pete Wilson, a Republican, appointed him as a municipal judge in 1995. Three years later he became a Superior Court judge for Yolo County; the 2008 election was the only time he ran opposed. Fall also teaches judicial ethics to other judges around the state.

He spoke with KHN in his chambers in Woodland, California. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: When did you realize you had a problem dealing with stress?

I’d been on the bench four or five years. I was leaving a committee meeting in the Bay Area for the California Judges Association, and I got to my car and started the engine, and all of a sudden my left shoulder and arm were numb. My first thought was a heart attack and my second thought was a stroke, but then the numbness diminished. The doctor said it was stress, and I said, “What do you mean, stress?” He said, “You don’t get it. Your job is at a stress level that most people don’t deal with, and you don’t recognize it because you’ve been dealing with it for a few years now.”

Q: That conversation with your doctor was 20-plus years ago.

Right. And it came to a head when I finally got a medical diagnosis regarding mental illness in 2008, after an attorney decided to run against me. The stress went to 11 immediately. It built upon itself and eventually got to where I would wake up at midnight and then stay awake for the night, feeling overwhelmed, feeling some depression, feeling some anxiety.

Q: Was it the idea of having to campaign for yourself that was the stressor?

Exactly. Some judges seem to thrive if challenged, and I’m happy for them. I speak in public regularly, but to do it when I was trying to keep my job was brand-new. The essential diagnosis was generalized anxiety disorder, with depressive episodes. We found some medication that worked for me, and that is important, because there are a lot of medications out there. Finding the right one and the right dosage is key.

Q: You wound up winning that 2008 election.

Handily. And the day after the election, I slept like a baby, and I woke up the next morning with absolutely no anxiety. It was the first time I’d had that kind of night’s sleep and that kind of waking moment since the first day someone announced to run against me. But I’ve had recurring episodes of anxiety since then, mostly having to do with my father’s health. Going back to my time in community college, I actually had a panic attack during an algebra final.

Q: Your father passed away in 2019. Then, in 2020, the pandemic hit.

And pandemic stress is real. We have pandemic rules in place, and it is my job to enforce those in my courtroom. Every morning, I’m reminding people how to wear a mask properly, and I am conducting remote appearances or in-court appearances. The level of attention that I have to give to things that people would say aren’t normally a part of a judge’s job is just very high.

Q: Why did you decide to make your story public?

The common statistics are that 20% to 25% of our population has anxiety or depression — or both. There are a little over 1,700 judges on the bench in California. And what that means is, statistically, 400 of them have anxiety or depression or both. I thought, somebody should speak about this in a way that starts to remove the stigma, that says this is just part of being in our culture, that anxiety and depression are real medical issues. People in all professions deal with these medical conditions: teachers, physicians, journalists, grocery clerks, whatever. I deal with them, and it does not disqualify me from being on the bench.

Q: Considering the political history and Thomas Eagleton’s experience, did you hesitate, given the potential stakes?

I did take a moment to count the cost. The benefit of getting my story out in an effort to encourage others, inform families and friends, and work to destigmatize mental illness far outweighed any flak I might have faced in an election campaign.

Q: Do you employ other mental health strategies besides medication?

I exercise six days a week. I run and I lift weights and stay on top of that. Eating right. I had no caffeine for the five or six months that I was dealing with the worst of this, and I love coffee. I’m also very far along the spectrum toward introversion and need to have my alone time to recharge. So that is another tool that I use, especially when stressful things come up, which may mean that I say no to some things that I might normally say yes to.

Q: One thing that didn’t change during all this was work. You continue to perform at a high level in a high-stress job, which is one of the things you write about.

Let’s say an auto mechanic has a rotator cuff injury that becomes a chronic condition. This person needs to find a way to still do their job while accommodating the fact that one of their shoulders may not be as strong or limber as the other. Nobody goes to the mechanic and says, “You’re disqualified from doing your job. Go home.” Mental illness is the same. There are tons of ways to get the job done if you have anxiety or depression. It simply requires that same type of attention: This is my condition. This is my job. What do I need to be able to carry out my job that is appropriate? What it does not do is disqualify.

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.