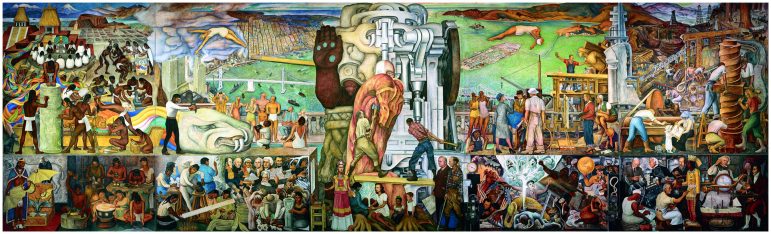

Before the limber figures, the picaresques, the colorized Aztec myths, before anything else, you’re confronted with the sheer scale of the towering fresco. Diego Rivera’s “The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on the Continent” (1940), aka “Pan American Unity,” stands 22 feet high and 74 feet long, and it’s unlike any narration you’ve seen before. Summarizing the mural in a neat paragraph is a fool’s errand.

The artist has crafted a symphonic ecosystem in which all the action takes place simultaneously. The past jostles with the present for supremacy. Cause and effect co-mingle. On the left-hand side, Rivera devotes a full one-fifth of the surface to life in the pre-Columbian continent. Stone masons fashion sculptures; artisans smelt gold and precious stones into jewelry, and the faithful worship the snake deities Cōātlīcue and Quetzalcoatl. The rightmost portion pictures a cross-section of Californian history: Forty-niners mine gold, lumberjacks collect timber and railroads plow westward. Labor is celebrated as an engine for industry.

If there is a chronology, it moves from the outside in. An imposing serpentine machine hangs dead center. It’s certainly modern and eye-catching, but how does it work? As Rivera has designed it, the inputs of history, industrial power and human labor (on the left and right) feed into this massive machine to “produce” the defeat of Nazism. A larger-than-life arm draped in the American flag emerges from the machine to quash a smaller swastika-tattooed hand. It’s a clever allegory, and visitors enjoyed it. In the two hours I spent with the 10 panels — now on display on the street level of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art — about three dozen people were gathered at any given moment to gaze at the mural.

People love Rivera’s work. Yes, his gorgeous illustrations and color palette play a part, but I think he draws sizable crowds because he speaks to viewers in an accessible visual language. He’s playful, humorous, biting. It invites you in, and once he’s captured your attention, you savor a scenery that teaches you to reassess your assumptions about class, about history and, most importantly, about power.

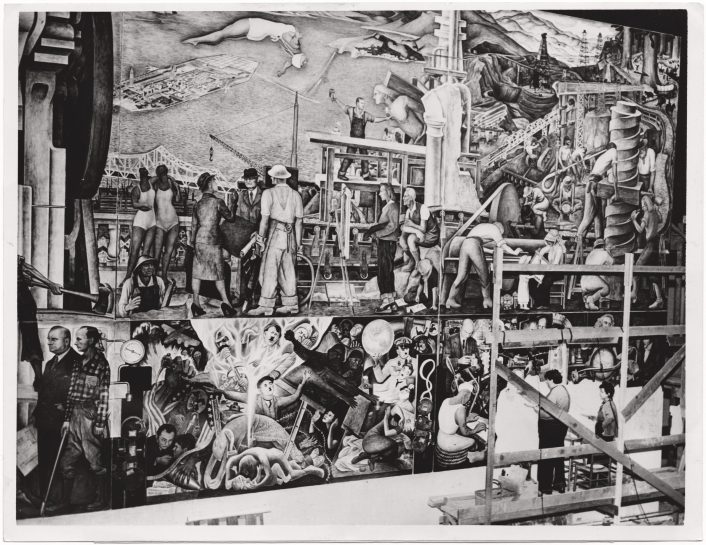

Diego Rivera was known to paint at breakneck pace and under punishing conditions. He kept his studios frigid — with temperatures rivaling an ice chest — to slow the lime plaster of his frescos from drying, thereby clawing back precious time to paint. He often clocked 14-hour days, sometimes even sleeping on the scaffolds surrounding his frescos so that wasteful commutes wouldn’t eat into his workday. By the time of each unveiling, he and his team would be exhausted. There’s a shiver of urgency to his workaholism, as if something — inspiration, maybe, or creative power — might desert him were he too slow to lock his designs in plaster.

Yet, speed did not distract him from clarity of vision. Despite his frantic tempo, churning out masterpieces every few months or so for three decades, his attention to historical detail is thorough. Nothing discernible is lost in the scramble. He always did his homework, poring over textbooks to accurately depict the intricacies of local history and class struggle that defined his Marxist understanding of global politics.

He wore his beliefs on his sleeve, especially his Marxist bona fides, which earned him a reputation as a firebrand and a pinko. Communist affiliations didn’t always endear him to American audiences, a fact that holds true today. (While I was jotting down notes for this essay at SFMOMA, a man approached me and, in our brief conversation, was quick to remind me that Rivera was a Commie.)

This life-long proximity to anti-capitalism and revolutionary ideology meant Rivera was never a stranger to controversy. In 1933, the Rockefeller family commissioned him to depict “Man at the Crossroads Looking With Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future.” Before the fresco was completed, however, construction stalled at the foot of brewing public outrage.

The cause of the scandal? Rivera had snuck in a portrait of Vladimir Lenin and a scene from a Soviet May Day parade, unbeknownst to his patrons. A media frenzy ensued. Rockefeller asked Rivera to remove the revolutionary’s likeness from the mural. But Rivera refused. In what turned out to be a painfully clairvoyant foreshadowing, he claimed that “rather than mutilate the conception,” he would “prefer the physical destruction of the conception in its entirety, but preserving at least its integrity.”

Rivera was paid the remainder of his $21,000 commission, and the mural was summarily chipped off the lobby of 30 Rockefeller Plaza. (The jury is still out on whether Rockefeller or his chief architect, Raymond Hood, ordered the painting destroyed.)

Though he would reproduce “Man at the Crossroads” in Mexico City’s Palacio de Bellas Artes a year later, the effacement still stung. Rivera mourned the fate of his “murdered painting” for months and slumped into a depression, abandoning his cherished murals entirely for easel paintings along the way. In these fallow years (1936-1940), his workload shrank, commissions stopped entirely and his marriage to Frida Kahlo crumbled, a result of his notorious womanizing. It was only when he received a commission from San Francisco in the summer of 1940 that he recovered from the blow and picked up the fresco technique again.

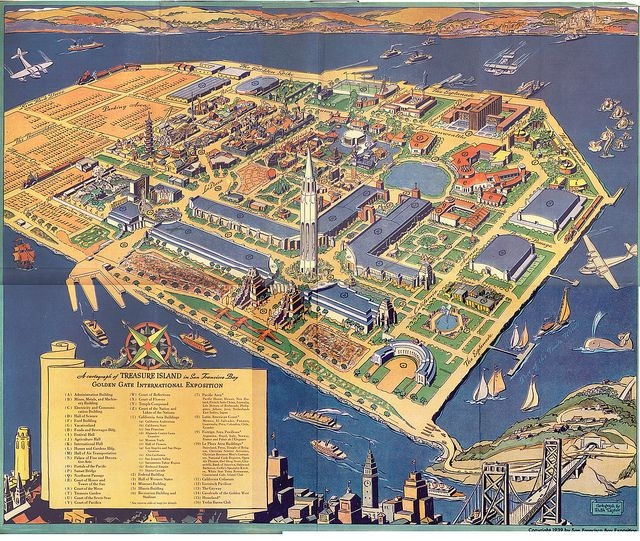

Lapped by the bay’s salty air at Treasure Island, Rivera painted “Pan American Unity” over a brisk four months. He worked in front of a crowd for the Golden Gate International Exposition’s Art in Action exhibition, which brought sculpture and painting and printing and mosaics down from the rarefied heights of the museum and into the streets.

Among his collected body of work, the mural stands out as a bit of a misfit. For a figure so associated with his obdurate attitude and avowed Marxism, it’s strange to find Rivera striking a conciliatory tone here, almost as if he’s pandering to the capitalists he otherwise disdained. Take his portrait of Henry Ford in the bottom right-hand side. The tycoon grins, gazing at a Ford V-8 fuel pump. His body is obscured from the waist down by a propeller engine in a nod to his company’s work in producing war matériel. Miniature employees toil on a conveyor belt at his back to make the product he admires, workers whose union organizing he denigrated and violently suppressed. (“People are never so likely to be wrong as when they are organized,” he said in 1922.)

It ought not be forgotten either that Ford espoused staunch antisemitic ideologies and expressed his allegiance to the Third Reich through his business dealings: Ford-Werke AG, the German subsidiary of Ford Motor Company, produced vehicles for the Nazi regime. In July 1938, Hitler awarded Henry Ford the Grand Cross of the German Iron Eagle, which Ford refused to return, and in April 1939, Ford-Werke donated 35,000 Reichmarks to Hitler’s 50th birthday fund. (A news reporter visited the future Führer in 1922 and discovered he kept a large portrait of the American business magnate in his office.)

Why paint this man with such an unusually gentle brush? If wage labor is exploitation, as Marx theorized and Rivera no doubt believed, why celebrate capitalists at all? Was Rivera reneging on his claim that “the role of the artist is that of a soldier of the revolution”?

I don’t think so. I imagine him grappling with a bigger picture. Rivera completed his fresco at the tail end of 1940, a year before the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor and months before the German invasion of the Soviet Union would galvanize public opinion in favor of intervention. Many Americans at the time believed World War II to be a European war, an interstate squabble external to American interests.

News from Europe, meanwhile, was grim. The Luftwaffe’s unrelenting blitzkrieg campaigns brought city after city to its knees. Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and France all fell in quick succession, and the Third Reich was consolidating power by courting allies: Benito Mussolini in Italy, Hideki Tōjō in Japan and, for a time, Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union. I picture these headlines piling up and up and up alongside a creeping sense of dread as Rivera tackled his commission with urgency — his message being, “If I can momentarily let these men off the hook, so can you.”

Why flatter these titans of industry? For the sake of pragmatism and survival, to put it bluntly.

But pragmatism is not the same thing as compromise. The mural isn’t shorn entirely of criticism — he still takes a swipe at Spanish colonization of the Americas — but it is sentimental, in as much as any plea to elites is bound to be. In the mural, we see a politically engaged, socially aware artist bargaining with the powers that be to turn the tide of the war. He implored them to live up to the mythical ideals of the U.S.’s Founding Fathers and Mexico’s Revolutionaries, whom he positions under the “Liberty Tree.” Maybe “entice” is a better word. Painting the muscular, Brown arm of America crushing the puny arm of Nazism with ease, for instance, was an attempt to unite a divided world against tyranny.

He even painted a how-to. American warships ought to leave port in San Francisco and set sail West toward the Japanese-occupied Pacific. No matter their product, America’s industrialists ought to produce for the war effort: Hollywood film to garner support for anti-fascism and industrial production for matériel. Oh, and per his guidelines, workers and women ought to have a place at the table, too.

Rivera recognized his instructions for an Allied victory for what they were, a colossal ask, and rendered them as equally colossal on his surfaces. Victory, he emphasized, would require all kinds of power — brainpower, manpower, firepower, creative power and economic power — from across the Americas. Only in this spirit of continental collaboration could the ghoulish trio of Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin be vanquished.

The mural cost $3,000 (an estimated $58,000 today, adjusted for inflation). It’s a pittance for what the director of SFMOMA, Neal Benezra, called “the greatest work of public art in San Francisco that very few people have had the opportunity to experience.” Quite the high praise for 60,000 pounds of painted plaster.

“Pan American Unity” was to be the last mural Rivera would create in the United States. His Communist sympathies during the Cold War all but confined his career to Europe and Mexico. The fraternity he hoped to manifest vanished almost as soon as the German Instrument of Surrender signed the Third Reich out of existence in 1945. (In fact, the prelude to the Cold War, Greece’s Civil War, broke out in the streets of Athens during World War II.) In its place, a new conflict splintered the globe as hot wars tore across the American continent, from Mexico and Guatemala to Argentina and Chile.

Though times have changed in the intervening decades, the urgency of Rivera’s thesis has not. Today’s emergencies require the same forward-thinking, collaboration and ingenuity that he pleaded for all those years ago, way back in 1940.

“Pan American Unity” will be showing for free on the street level of SFMOMA until summer 2023. The museum is open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Mondays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays and 1-8 p.m. Thursdays. General admission to the other floors is $25, and the first Thursday of every month is free to Bay Area residents. For more information, visit www.sfmoma.org.