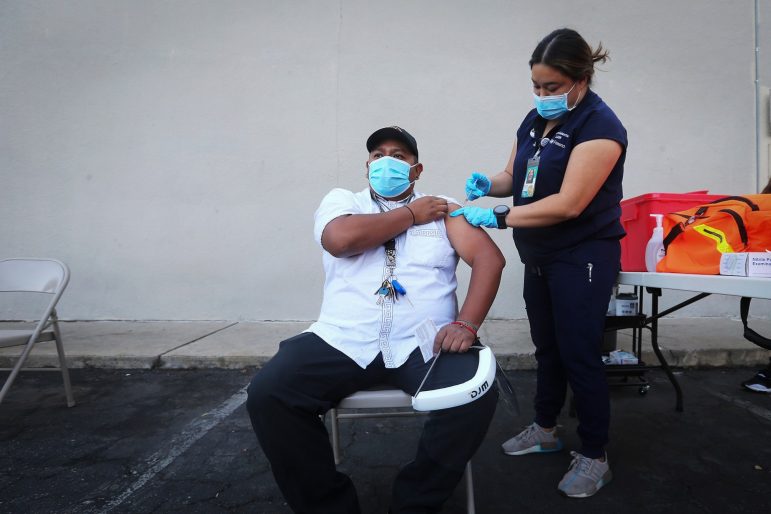

Ismael Patia and his family arrived at a COVID-19 vaccine clinic in downtown Fresno on a recent Saturday afternoon. His decision to get vaccinated had been a difficult one. But he finally was persuaded by an interpreter who talked to him in his native language, Mixteco, and eased his fears.

“I’ve been hearing about people dying of the vaccine,” Patia, a farm worker from Lagonia Yucutini in Guerrero, said in Mixteco.

Patia’s language has no written form, and he is one of the hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Mexico and Guatemala in California who speak Indigenous, non-Spanish languages and have struggled to stay informed and healthy during the pandemic.

Often unvaccinated, with limited access to information about the vaccines, many of these immigrants are farmworkers who live in poverty, with low wages, less access to health care and crowded housing. Combined with the language barriers that allow pandemic misinformation to spread, they are particularly vulnerable to infection and serious illness.

State and county officials have tried to reach them: They have provided COVID-19 materials translated into Mixteco and other Indigenous languages. And many counties teamed with Indigenous community groups to launch their own extensive outreach programs and clinics.

But so many migrants in California — including 350,000 Indigenous Oaxacans — speak such a vast variety of languages that advocates say the efforts are insufficient. And they worry that many people are still falling through the cracks and remain unvaccinated.

“(Indigenous farmworkers) are extremely poorly vaccinated, especially in the rural areas,” said Rick Mines, a former U.S. Department of Labor researcher who has conducted farmworker surveys for more than 40 years, including 12 years directing the National Agricultural Workers Survey.

“The Indigenous earn less, pay for rides more, live in more crowded apartments and are covered by health care less often. So, though we can’t know that they get fewer vaccines on average, we suspect that it is true due to these associated conditions,” he said.

When the Delta variant sent California’s COVID-19 rates spiking again during the summer, many Indigenous Mexican and Guatemalan immigrants were hit hard.

“Everyone knows someone that has passed away, or multiple people that have passed away because of COVID,” said Sarait Martinez, director at Centro Binacional para el Desarrollo Indígena Oaxaqueño, which serves Indigenous people in the Central Valley and Central Coast.

Indigenous-speaking immigrants told CalMatters that the myths and misconceptions that proliferated focused on fear that the vaccine would harm them, even kill them. One person said after his first dose he was afraid to get another because he thought the side-effects were a sign that the vaccine was harming him.

Most of the people who speak Indigenous languages live in farm regions — primarily the Central Coast and the Central Valley. Others live in cities and are essential workers in sectors like the restaurant or garment industry.

The variety of languages and dialects hampers health officials’ efforts to communicate vital, complex and highly personal health issues related to COVID-19.

In California agriculture, workers speak 23 Indigenous languages, representing 13 Mexican states, according to the 2010 Indigenous Farmworkers Study, which Mines directed. Most spoke a variation of Mixteco, Zapoteco or Triqui. In Guatemala, Indigenous people speak 24 languages, including 22 Mayan languages, according to Translators without Borders. In California, they speak K’iche, Q’anjob’al, Mam and Akateko, among others. Many of these languages have dialects that vary from town to town.

Indigenous languages are usually not written, and many Indigenous immigrants are not literate. Community organizers say outreach on COVID-19 is most effective when it’s done in person or through audio and video formats.

“If it’s just written, it’s not going to reach these Indigenous communities,” said Aurora Pedro, who translates in Akateko for Comunidades Indígenas en Liderazgo and the Center for Indigenous Languages and Power, both based in Los Angeles.

Some migrants speaking Indigenous languages cannot read forms or retrieve the documentation necessary to get aid from state-sponsored medical programs.

“Part of the challenge (for Indigenous groups) has often been having access to someone’s guidance to be able to get the vaccine, and also, obviously, inform them about that vaccine and the reaction (side effects),” said Miguel Villegas Ventura, immigration project coordinator at Centro Binacional.

Ventura said he and other interpreters have gained trust by reaching out to people in the fields and knocking on doors, informing people to get vaccinated and guiding people through the registration process. With that trust, they’ve persuaded people to get vaccinated.

Elvia Vasquez, an agricultural worker in Fresno who is Mixteco, from Peña Larga, Oaxaca, knows many people who lost loved ones to COVID.

“Luckily, thank God, that with us it didn’t happen,” Vasquez said in Spanish, “But all my family had COVID except me, my son and my husband. We are a family of 20. Everyone got it except us.”

Although she does not speak Mixteco, she lives around people who do. Many are not vaccinated because they have not had access to accurate information and many have doubts because of how quickly vaccines became available, she said.

Vasquez, like many of those at the Oct. 9 vaccine clinic in Fresno, chose to get vaccinated because organizations like Centro Binacional and Comunidades Indígenas walked them through every step of the process. Translators also parse convoluted materials to fit Indigenous languages — a pandemic, for example, would be described as “a sickness going around” — to make it easier to inform community members on everything from the latest variants to vaccine announcements.

Community organizers say they need more interpreters and staff to run their outreach programs and clinics. In August, nearly 120 people attended vaccines at Centro Binacional’s monthly clinic in Fresno.

Although these outreach efforts have been significant in making sure people are vaccinated, “it’s not enough,” Ventura said.

A lack of COVID data

To those working with Indigenous people from Mexico and Guatemala, the problems with vaccination access seem clear. But there is little data to back it up.

Advocates and researchers say data about the infection and vaccination rates among the state’s indigenous-speaking people doesn’t exist, even though there are hundreds of thousands of them.

This poses a problem for community groups that want to quantify which language gaps still exist and for agencies trying to determine where vaccine outreach is still needed.

Because governments only ask for broad identification, such as Latino or Black, when people get their vaccines, Martinez said many Indigenous people will either identify as Latino or “other.” In state and county health data, people might be counted as Spanish-speaking, despite speaking languages like Mixteco, Zapoteco and Triqui.

Sara Bosse, director of public health at Madera County, said she “highly suspects” Indigenous farmworkers there are poorly vaccinated. “But I actually just don’t know because the data isn’t collected,” she said.

Some small-scale efforts have been made to track Indigenous-language populations, such as We are Here, a mapping of some of Los Angeles’ populations. It’s the first time anyone has mapped the ZIP codes of these language groups in the city, Pedro said, providing vital information that affects government support and funding.

The California Department of Public Health said in a statement that while it may be able to estimate COVID figures for these groups in the future, it doesn’t have the resources to do so at this time.

Experts say examining individual ZIP codes can offer a snapshot of the vaccination problem. For instance, the 93268 area code of Taft in Kern County is identified as having predominantly Mixteco speakers from San Pablo Tijaltepec in Oaxaca, according to Mines’ research on Indigenous hometown networks. In this area code, only about 36% of the population was fully-vaccinated as of Nov. 2, according to state data.

Migrant communities are growing

Pedro said the need for more Guatemalan translators reflects the growing immigration from Guatemala to the United States. Pedro canvasses the MacArthur Park neighborhood in South Los Angeles and said she sees increasing demand for Q’eqchi’, Mam and Q’anjob’al — all Indigenous languages from Guatemala.

Ventura, who translates Mixteco, said increasing numbers of Mam language speakers from Guatemala have settled in the Central Valley. Centro Binacional is working to find them, he said.

Centro Binacional is one of the few organizations in the state to employ multiple Indigenous-language translators. Yet it did not have “sufficient staff or resources to scale up their outreach” at the beginning of the pandemic, according to the Indigenous Agricultural Worker report, released in October by the California Institute for Rural Studies.

Michael Méndez, a professor of environmental policy at the University of California, Irvine who studies how the lack of focus on Indigenous immigrant communities in wildfire planning exacerbates inequality, said this plays into a “Latinization” of these groups, which are often seen as Latinos despite distinct languages and cultures.

Méndez’ research highlights how translation services, among other disaster preparedness measures by the Office of Emergency Services for Indigenous people, have been overlooked for years despite California’s sizable population. The state auditor’s office 2019 report lambasts the state for not prioritizing those with limited English-language proficiency.

“Not having appropriate — culturally, linguistically — disaster planning and response can mean life or death for many of these Indigenous communities,” Méndez said.

Many of these migrants already faced widespread medical inequality before the pandemic, according to the Indigenous Agricultural Worker report. Language barriers, lack of funds or insurance and deep-seeded medical mistrust all play a role.

County and state outreach

The state’s COVID-19 Health Equity Pilot Projects Program awarded $5 million in grants to 19 community-based organizations. Two of them — Mixteco Indígena Community Organizing Project and United Way Fresno and Madera — serve Indigenous communities. The state also put together a vaccine advisory committee that included Indigenous immigrant advocates.

But Bosse of Madera County said the state money is spread thin statewide among a lot of large community organizations, and their programs “don’t necessarily get into… niche outreach” for groups like Indigenous language speakers.

In response, some counties like Madera started their own extensive efforts. Eight of 11 counties contacted by CalMatters — Madera, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz, Monterey, Los Angeles, Tulare, Kern and Fresno — partnered with a community organization that could translate information into Indigenous languages. Kern County asked the state for translation services to assist with outreach. Two counties, Kings and Ventura, did not respond for comment and one, Yolo, said it did not provide Indigenous language services.

Santa Cruz County’s Health Services Agency established a Language Line a year ago to connect non-English speaking residents with COVID resources and vaccine appointments. Spokesperson Jason Hoppin said 30% of calls are in Mixteco and 2% are in Triqui. Operators scheduled 200 vaccine appointments.

Fresno, Monterey, Tulare and Madera counties partnered with Centro Binacional to provide outreach services in Indigenous languages and host vaccine clinics. Santa Barbara County partners with multiple organizations including Mixteco Indígena to provide vaccine outreach to Indigenous farmworker communities.

Los Angeles County works with community health workers to do outreach and translate materials in languages such as Kaqchikel, K’iche, Kanjobal. The county has also partnered with Comunidades Indigenas for vaccine outreach and to distribute aid.

“That helps us with the immediate things and it is definitely not enough,” Martinez said. “At least it ended up covering some of the Central Valley and some parts of the Central Coast, but there’s other communities that we’re not touching.”

The state health agency says it’s continuing to provide grants for future projects. The Office of Health Equity contracted with UC Davis Health and community organizations to run vaccine and testing clinics for immigrant and farmworker populations in Sacramento and Yolo counties from October to March 2022. The initiative will include Mixteco speakers.

Outreach is labor-intensive, but reaching out personally to individuals may be the only way some people ever get vaccinated.

In Fresno, Patia said without community-based help, he would have struggled to find reliable information about the safety of the vaccine. Now he says he will encourage others to get their shots, too.

“I will tell people to come,” he said, “because everything is okay.”