Social distancing may be good for public health these days, but it isn’t good for the California economy. As the coronavirus pandemic forces millions of residents to cancel dates and travel plans, retreat from social life to shelter in place, key cogs of the state’s economic engine are grinding to a halt. That’s an unprecedented shock for a modern economy, experts say — one that will test the resilience of California’s decade-long boom and the adequacy of its $18 billion cash reserve.

What we know so far: The coronavirus is almost certainly causing the first pandemic-induced recession of the postwar era. For millions of Californians and their families, that may mean less work, lower income and more financial stress, particularly for those least able to weather the shock: Californians living at or below the poverty line, those without savings or outside financial support and people living on the street.

What we still don’t know: how bad this will get. Never before in the state has so much business activity come to such an immediate and widespread stop at once, the experts say. Policymakers, businesses and regular Califorians are just beginning to grapple with what this all might look like.

“It’s so much larger than anything we’ve encountered before,” said Jesse Rothstein, professor of public policy at UC Berkeley. “I think this is going to be larger than the Great Recession. I hope it doesn’t last as long, but the magnitude of the shock is bigger.”

The state’s enormous, diversified economy — fifth largest in the world — isn’t reliant on any one industry. But sunny California’s tourism, hospitality and retail sectors — together providing about one in five jobs, according to state statistics — are proportionately larger here. So are transportation, warehousing and other trade-related industries. All are taking the most immediate financial hit.

And while the tech sector that has driven so much of the state’s economic growth may very well be better equipped to handle — even prosper from — the new housebound economic order, such a dramatic slowdown is likely to leave few sectors unscathed.

“A month ago California was in a situation where we still had one of the strongest economies we’ve ever had,” said Rob Lapsley, president of the California Business Roundtable, which represents major employers in the state. “Now, the underlying analysis on all of this is uncertainty. Nobody knows. We’re in uncharted territory.”

Will the coronavirus crisis cause a recession?

Earlier this week, President Trump said the U.S. economy may be headed for a recession. Some experts say we’re already there.

According to a team of economic forecasters at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, the country likely entered recession this month. California, said Jerry Nickelsburg, who directs the forecast, probably will get hit harder than the nation as a whole.

“Over the last week … transportation in the U.S. has plummeted,” he said. “People are not going on vacation. Transatlantic flights have been canceled, which means less travel but also takes a lot of (air) cargo out of the system.”

The forecasters project the state unemployment rate to go from just under 4% in January to 6.3% by the end of the year.

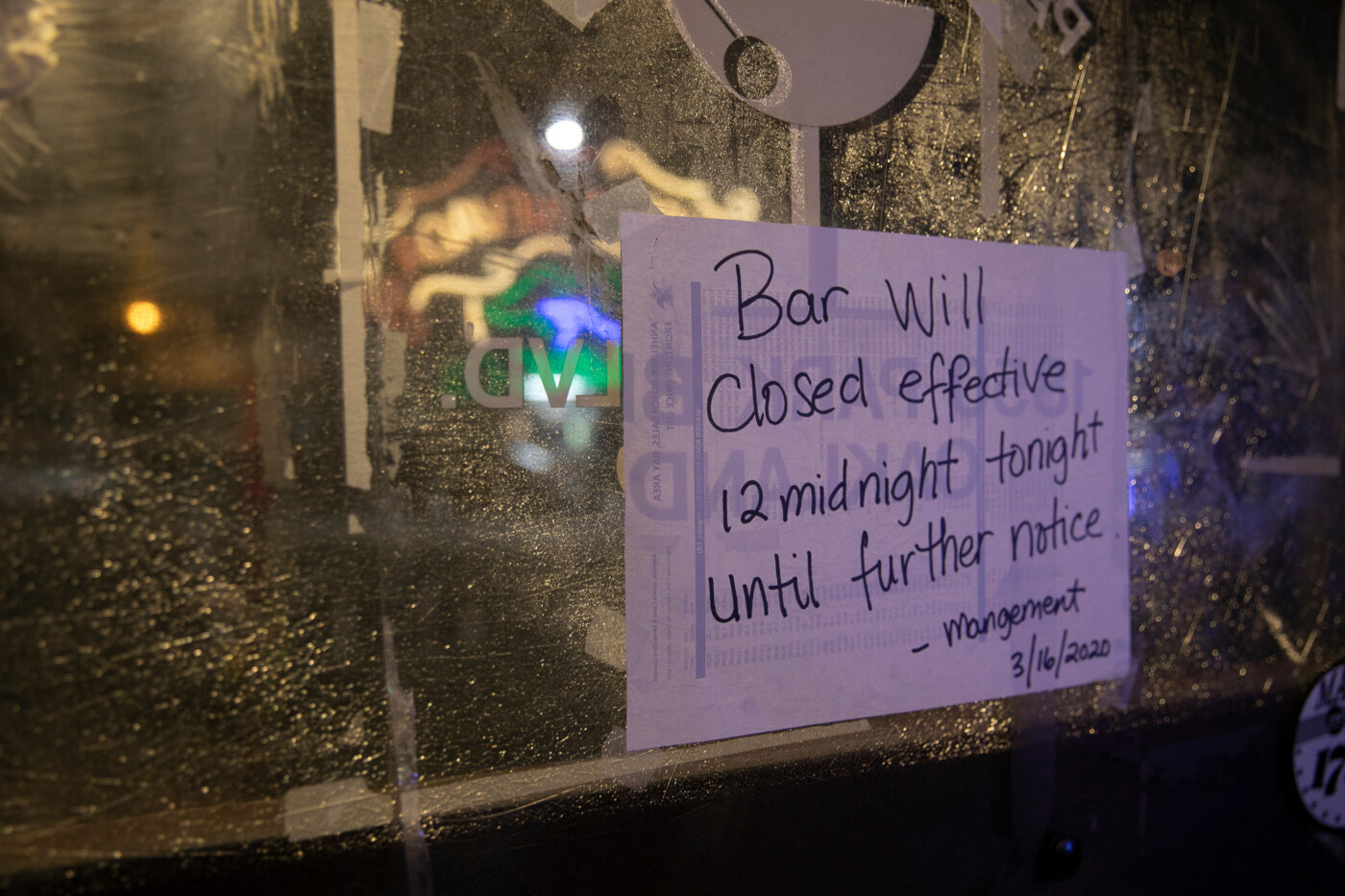

Hitting bars, restaurants, gyms and hotels especially hard, the economic constriction, like the contagion that precipitated it, is likely to spread quickly as newly unemployed workers stop spending, shuttered businesses cut off their orders and lenders and landlords stop receiving their monthly checks.

“You add it all up and who is holding up the economy? Health care,” said Nickelsburg. “That’s not enough.”

Who gets hit the hardest?

During a public health emergency, when millions of people are being told to steer clear of restaurants, bars, hotels and airplanes, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to surmise which industries will suffer the most.

Liz McAlpine was a bartender in Oakland before the restaurant where she works went take-out only, cut her schedule to four hours a week and put her on boxing and bagging duty for deliveries. She makes about $14 an hour and can no longer count on the tips that one made up a considerable portion of her earnings. She had side jobs that have fallen through. She said she has $17,000 in student loans to repay. Her three housemates are now out of jobs, too.

“None of us have a Plan B or C or D,” she said. We have no idea what we’re going to do. I have a tent.”

The pandemic has hammered both the state’s neighborhood bars and bistros and its biggest tourism draws. This month, Disney shuttered the gates of the Magic Kingdom, and the Coachella music festival was postponed from April to October. The opening of a 466-room Marriott in Anaheim was canceled and has yet to be rescheduled while, nationwide, roughly 8 in 10 hotel rooms sit empty.

Retail, hospitality, food and travel are not just major employers in the state. They also hire a disproportionate number of California’s low-wage workers.

The top job categories for the state’s working poor, according to an analysis by the Public Policy Institute of California, include janitorial services, food preparation and jobs in the arts and entertainment industry. Another PPIC analysis estimates that 22% of food and accommodation workers in California are at or below the poverty line already.

“Poverty in California is really about working poverty,” said Sarah Bohn, one of the authors of both analyses. “The social safety net plays an important role, but for the vast majority of low-income families, it’s really about their earnings.”

Many of these workers are “already vulnerable (to) becoming homeless or suffering other sorts of housing instability,” said Chris Hoene, executive director of the California Budget and Policy Center, a think tank that focuses on low-income Californians. “What will change in their hours or work schedule mean for them?”

And when the public health emergency does end, many laid-off workers may not be able to count on getting their old jobs back, said UCLA’s Nickelsburg. One possible side effect of this downturn is that it will accelerate trends that were already developing before the pandemic.

”Brick-and-mortar retail was already contracting,” he said. “To the extent that (the epidemic) forces more contraction for brick-and-mortar, you might not expect all those businesses to come back.”

Meanwhile, Amazon announced that it would be hiring 100,000 workers to handle the flood of online delivery requests. A company spokesperson said 12,000 of those hires are expected to be in California.

Rachel Michelin, president of the California Retailers Association, which represents the state’s largest retailers, said consumers shifting to online sales may “might make a dent” in the financial landslide now burying the association’s members — but only a small one.

Even if the shelter-in-place order is lifted, she said, “you have people who aren’t working, consumers who are now wondering, ‘Am I going to have a job?’” she said. “I think people are going to think twice about buying things they don’t necessarily need until we get past this.”

A prolonged economic freeze would be particularly hard for smaller businesses that don’t have the cash reserves to cover overhead like payroll, rent, mortgages and taxes until things improve.

“How do you give restaurants, in this case, the ability to hibernate?” said Jot Condie, president of the California Restaurant Association. How do they “ramp down operations so that when the all-clear is given, they can hit the switch and their workers can start working again and get back into the game, and restaurants can be open for business?”

With slim margins and high overhead costs, Condie said, many restaurants won’t survive much longer than a month without outside help.

“How do you give restaurants, in this case, the ability to hibernate? [How do they] ramp down operations so that when the all-clear is given, they can hit the switch and their workers can start working again?”

—Jot Condie, California Restaurant Association

Ann Callahan owns and operates a bed-and-breakfast in San Diego’s Hillcrest neighborhood, a cozy getaway spot that has become a kind of pandemic boarding house.

Although all of her typical conventioneer clients have cancelled, she still has four rooms booked. Three are occupied by out-of-towners who want to spend the crisis close to loved ones in the area, and a couple from London whose cross-county American holiday was abruptly cancelled.

Callahan said she’s set up new protocols, making sure chairs are at least six feet apart and directing all guests to use hand sanitizer before using appliances. She said she’s lucky to have enough money saved up to weather a prolonged crisis. But no one knows how prolonged this one will be.

“It’s not like 9/11. When it hit us, everything closed. But then we knew the worst of it was over going forward,” she said. “We don’t know when we’ve hit the peak of the pandemic.”

The state is prepared to extend hundreds of millions of dollars in loans to small businesses through its infrastructure bank, the treasurer’s office and the office of the Small Business Advocate. The federal Small Business Administration also announced that it would make loans for post-disaster rebuilding available to small companies weathering the shutdowns.

“The biggest thing we’ve been hearing from employers is (they’re) concerned about capital: How do they make payroll? How do they ensure that business can stay open if they’re seeing a massive decrease in demand for their goods and services?” said Mark Herbert, director of Small Business Majority, a group that lobbies on behalf of small businesses in Sacramento.

And in a sign that the slowdown is sending business both small and large reeling, shipments in and out of California’s major ports have started to slow. That’s likely to affect the state’s trade, transportation, warehousing and manufacturing sectors.

In Los Angeles, cargo volumes last month were 23% lower than February 2019, and 41 vessels have already canceled their scheduled trans-Pacific voyages to and from the port through April. That’s up from a typical 17 cancellations over the same period.

In the Long Beach and Oakland, the state’s two next largest ports, volume is also down, with cancellations up.

That’s not an unprecedented dip, said Mike Zampa, spokesperson for the Port of Oakland. There is always a slump in Pacific Rim trade in February, as factories across Asia shutter for the Lunar New Year.

“Once the factories come back online, the order of imports tends to come back up,” he said. “But there’s no question at all that the spread of the virus has affected imports throughout the U.S.”

Are there any economic winners in this pandemic?

As consumers stock up, stay home and try to take the edge off, supermarkets sales, online retailing and demand for cannabis and booze have been skyrocketing.

All that online shopping ought to be good news for the Inland Empire’s burgeoning warehousing and logistics industry, said Rob Lapsley of the Business Roundtable. Amazon operates more than a dozen fulfillment centers in the region.

Warehousing and logistics have been “the backbone of that region’s growing economy since the recession, a completely enhanced logistics economy down there that’s been replacing a lot of our manufacturing jobs,” he said.

But online shopping isn’t likely to make up for losses elsewhere. And the surge in spending on non-perishable groceries, toiletries and marijuana now may simply lead to less spending in the future. (Those who loaded their trunks with toilet paper this week may not need a re-up on new rolls anytime soon).

The biggest employer in the California private sector is certain to see a huge surge in spending throughout the pandemic: the health care industry. Hospitals, clinics and labs across the country are now scrambling to ramp up capacity to test, treat and contain those who are infected. Policymakers in Washington and Sacramento are scrambling too, which will likely mean billions more in government spending.

That could benefit workers in certain niche industries, like the country’s medical-device manufacturers, which are rushing to meet demand as hospitals and clinics run out of equipment. Roughly 17% of those workers are employed in California.

But the surge in demand for medical services could bring its own disruptions.

“If there are a lot of cases in the ICU, hospitals are going to have to try to collect from either insurers or patients, and the question is whether anyone will have enough cash flow to service that while the hospitals are overflowing,” said Mathy, from American University. “This would be a very bad time for hospitals to start going bankrupt.”

And the various jobs that fall into the “health care and social assistance” category created by federal economic analysts is broad. Most health care work is not related to the coronavirus.

Kate Schmidt, a retired Olympian javelin thrower, now runs her own rehabilitation service, helping her well-heeled clients at their homes. It’s a business that takes her from house to house, touching her clients, their belongings, their pets.

“I do all of the things we aren’t supposed to do now,” she said. And many of her clients are of an age that puts them at higher risk of lethal infection.

If she were responsible for transmitting the virus to any of them, she said, “I would never be able to forgive myself, so I pulled the plug.”

She’s put her business on hold. Unlike many personal-care workers, she has enough money saved to make it through a few months without income. But she’s still trying to find a way to keep her business operating.

“I’m trying to figure out Zoom, to see who amongst my clients will take me on their phone in their house,” she said.

A spokesperson for Zoom, the San Jose-based teleconferencing company, declined to share new usage numbers. But if any sector is equipped to deal with, and benefit from, California’s new work-from-home regimen, it would be the tech sector.

The demand for remote-working options to keep housebound people productive could become a silver lining in what is otherwise a very dark economic cloud for the state. That’s to say nothing of the demand for productivity-diminishing entertainment options available at such online sites as Netflix, based in San Jose, and Burbank-based Disney, which recently debuted its wildly popular Disney+ streaming service. Neither company responded to requests for new subscription data.

But not all of Silicon Valley can serve consumers stuck in their living rooms, said Carl Guardino, CEO of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group. Apple is in the manufacturing and retail business. Square, the San Francisco company that helps businesses process credit-card purchases on smartphones and tablets, depends on the health of small businesses. AirBnB is in the hospitality industry.

And electric-car maker Tesla “is obviously an innovation-economy company,” said Guardino. The firm, which employs roughly 10,000 people in the Bay Area, is suspending production at its Fremont factory as of March 23.

Investors on the whole don’t seem to think that tech is all that much more insulated than the rest of the economy. Since the beginning of the year, the S&P 500 Index, which tracks the performance of stocks belonging to the country’s largest companies, has fallen by 26%. The NASDAQ Index, which includes tech giants like Apple, has plummeted by 21%.

What about the state budget?

Call it Jerry Brown’s “I told you so” moment.

In the years after the Great Recession, Brown pushed the state to build a stockpile of cash that fiscal analysts say should weather a mild recession without necessitating serious cuts in funding for public schools, colleges or social-welfare programs.

According to the Department of Finance, the state has roughly $21 billion in reserves, most of that in an $18-billion rainy day fund. And in case that starts to run low, the state controller reported having nearly $42.8 billion available as cash that could be shifted among various state agencies to keep things running.

With any recession, the state budget takes a hit from both ends. As economic activity slows, the flood of revenue destined for state coffers dries up. In the short term, as panicked investors cash out of the stock market, there may actually be an increase in capital-gains tax revenue, which is paid when stocks, bonds and other assets are sold.

But in the longer term, “basically every source of state tax revenue that you can imagine is going to be down,” said Jeffrey Clemens, an economist at UC San Diego. That includes sales taxes, which depend on transactions in the now-paralyzed retail sector, and the state’s progressive income tax, which is particularly prone to whipsawing with each boom and bust.

We may not know the extent of the damage for a while.

Normally, budget bean counters rely on the bulk of filings during tax season to flesh out the state’s spending plan for the coming year. But the state and federal governments are extending tax deadlines, which will give budget officials an incomplete picture.

On the other side of the equation, there’s now increased pressure on state spending. That would be true even during a typical downturn, as more Californians turn to state programs like unemployment insurance, CalFresh food stamp benefits and CalWORKS, the welfare program.

Add to that the unique costs of addressing a public health crisis.

State legislators passed a bill allowing Gov. Newsom to spend up to $1 billion “for any purpose,” with much of it likely to go toward expanding the capacities of hospitals to treat the severely ill and of public health authorities to set up testing and quarantine sites. In the months ahead, uninsured Californians may turn to Covered California, the state’s subsidized health insurance market, for coverage. And if infections ramp up as expected, low-income Californians are likely to increase their use of Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program.

State lawmakers will need to pass a budget by mid-June. Because California’s Constitution limits how much the state can borrow and for what purpose, the only way to patch a fiscal hole without cutting services or jacking up tax rates in the middle of a recession is to draw down the rainy day fund or turn to the feds for help.

It’s not yet clear what kind of help Washington might offer. The Trump administration has proposed sending many American households some $500 billion over the next two months, with the bulk going to low earners. They’re also proposing another $300 billion in loans for small businesses.

Unlike past recessions, when stimulus packages of tax cuts and new spending have been enacted to entice people to go spend money at restaurants, bars and shops, new public spending is likely to have a very different impact this time, said UC San Diego’s Clemens.

This time around, most of the financial support is likely to be directed at “making sure that people don’t default on mortgages or miss rent payments just because they were an hourly worker who had their hours massively cut back,” he said.

Allowing the private sector to wait out the crisis in suspended animation could soften, or least delay, stress on the state budget.

Beyond that, there’s the fiscal reserve.

“If there is any silver lining, it is found in the condition of California’s budget, which entered 2020 on strong footing,” Gabriel Petek, the state’s nonpartisan legislative analyst, wrote this week. Earlier this year, his office estimated that California’s nest egg is big enough to weather a recession “typical of the post‑World War II era,” with no need to find money elsewhere.

Normally, budget bean counters rely on filings during tax season to build next year’s spending plan. But the state and federal governments are extending tax deadlines, giving officials an incomplete picture.

But nothing about the current situation is typical.

“While it’s a substantial amount of discretionary reserves, we are anticipating that we need to do everything that we can to meet this moment and not go small,” Newsom said at a recent press conference.

And once that moment passes, the state’s longer-term fiscal future may look a little more grim.

With the collapse in stock prices, the state’s public-employee pension systems — mainly California Public Employees’ Retirement System and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System — are taking a beating.

At last count, the combined retirement liability for state workers and teachers topped $250 billion. And because the funds depend largely on investment earnings to keep up with pension checks, Wall Street’s rout will lead to bigger unfunded liabilities at CalPERS and CalSTRS.

“I don’t even want to think about the impact on the pension funds,” said Brad Williams, a veteran budget analyst and partner at Capitol Matrix Consulting. “We know that pensions were underfunded going into this, and…once you get behind, it’s hard to claw back, so we really need a bounce back in markets to avoid pretty dire circumstances.”

Just how bad will this downturn be?

The size of the economic hit will depend on the severity and duration of the public health emergency. On that question, uncertainty abounds. But most experts are projecting a range of outcomes that span from “very bad” to “very, very bad.”

The UCLA forecast projects a recession that will last through the fall. That assumes the worst of the pandemic will be over by summer.

“That’s based on very little data, but it looks like, in places like China and South Korea, that the number of new cases…is declining now,” said Nickelsburg. “So that’s what we’re basing it on.”

The best-case scenario, said Chris Thornberg, founding partner of the consulting firm Beacon Economics, is that social distancing measures will have their desired effect and slow the spread of the virus. In that relatively rosy picture, there is a sharp, but short-term, decline in retail and restaurant spending. But soon the public health emergency abates and economic activity revs back up within a few months. It’s what some analysts call a “V-Shaped” recession — down and then up again.

“If we have sufficient panic now” — meaning a coordinated pause of daily financial life — “it will be nothing more than a blip,” he said. “For once in my life, I’m espousing panic.”

But there are less rosy scenarios. If hundreds of thousands of people are sickened, if prolonged periods of isolation are mandated, if individuals and companies are pushed into bankruptcy in the meantime — or all of the above — “then swaths of people get laid off and that’s when it feeds back on itself.”

UCLA forecasts a recession that will last through the fall. That assumes the worst of the pandemic will be over by summer.

It’s not clear that a modern economy has ever experienced a disruption quite like this one.

In virtually every downturn in American history — from the Great Depression through the Great Recession — contractions have started in large, but not particularly labor-intensive, industries like manufacturing and construction. In general, said Gabe Mathy, an economist and economic historian at American University in Washington, D.C., spending on day-to-day things like restaurants, bars, gyms and shopping trips continues apace, offering some stabilizing ballast to the economy at large. Even in bad times, people still need to get their hair cut.

“During the Great Recession, spending on services was higher at the (lowest point), in 2009, than it was after the recovery,” he said. “Obviously this recession is going to look very different than the Great Recession.”

Mathy calls what we’re seeing now is a services recession — “the first one we’ve seen in world history” — and it’s hitting the economy in a sector that employs 86% of all American workers. The California labor force is particularly concentrated in the service sector.

“I don’t want to be too catastrophic, but the job losses we’re likely to see might be kind of eye-popping,” he said.

In a national poll sponsored by NPR and PBS and conducted in mid-March, 18% of respondents said they or someone in their household had either been let go or had their work hours cut.

In the second week of March, there were 58,208 applications for state unemployment insurance, an indicator of how many Californians have lost their jobs since the beginning of the public health crisis. In a live-streamed address this weekend, the governor said that the total clocked in at 135,000 on a single day last week.

The typical daily figure in the previous months was less than 6,000.

CalMatters’ Judy Lin, Jackie Botts and Anne Wernikoff contributed reporting to this article.