Updated Feb. 6, 2020.

Calling the bankruptcy of California’s largest investor-owned utility a “godsend,” Gov. Gavin Newsom has threatened a public takeover of Pacific Gas & Electric unless it can transform into a provider of affordable, reliable, clean and — above all — safe energy. That means no more ferocious wildfires sparked by PG&E equipment. That means no more fire-season blackouts that drag on for days or weeks, disrupting the state’s $3 trillion economy.

It has been a little over a year since PG&E sought Chapter 11 protection, fearful that it might be locked out of the capital market by mounting wildfire liability and a fire-prone, climate-driven future. Reorganization was intended to give the company breathing room, keep utility workers employed — and keep Northern California’s lights on.

PG&E hasn’t been without lifelines. Last year, the state created a fund to help utilities deal with the rising risk of wildfires. If PG&E emerges from bankruptcy by June 30, it can qualify for that assistance — something it desperately needs to get out of a hole created by nearly $25 billion in settlements with wildfire victims and insurers. One by one, as the current reorganization has proceeded, most of those victims, along with insurers and bondholders, have signed on to PG&E’s plan, in order to be repaid.

But PG&E also has a long, bitter history with Californians, from the lax maintenance that led to eight deaths in a 2010 San Bruno gas explosion to the groundwater contamination that prompted a class action lawsuit in the 1990s to the role its aging equipment has played in recent wildfires. Only Newsom, speaking for a distrustful public, now stands in the utility’s way.

Newsom has resolved to block the electricity provider unless it overhauls its corporate governance, refocuses on safety and opens itself up to state control if conditions become dangerous. He can do that: PG&E’s reorganization plan requires approval from Newsom’s appointees on the California Public Utilities Commission.

PG&E has pledged to bring in some new board members and a safety monitor. But the utility wants to keep its corporate structure intact and use stock to pay half of the settlement it owes victims of the fires caused by its equipment, essentially making them shareholders. Meanwhile, tree-trimming it was supposed to do to mitigate future risk remains backlogged. And even under its best-case scenarios, blackouts can be expected for another decade.

So can Newsom force change? And if he does, what might that change look like?

History isn’t on Newsom’s side, but …

Newsom has insisted “there’s gonna be a new company or the state of California takes it over.” But he hasn’t offered any specifics about what a public acquisition would look like – let alone mention that any takeover could cost $60 billion or more, a high price even for a state with an $18 billion rainy day fund. And bankruptcy court may be a difficult venue to do it.

“We haven’t seen the bankruptcy system in recent years used to dramatically alter the structure of a major privately owned public utility,” said Jared Ellias, law professor at UC Hastings. “This is new. There’s not a set of transaction documents sitting on anybody’s shelf.”

Still, state and local leaders don’t want to allow the status quo given PG&E’s poor track record.

One state senator has proposed a state takeover with the option to spin off local municipal authorities. A group of mayors led by San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo has an idea for starting a customer-owned electric cooperative that would provide power through their own generation plants or power purchases. And a less invasive proposal would add another layer of regulation through the appointment of a public administrator.

A December poll by the Institute of Governmental Studies at UC Berkeley conducted for The Los Angeles Times found fewer than 1 in 8 likely voters want PG&E to fix its own problems and maintain its current structure. There is no consensus, however, on what changes should be made. The poll found 35% of voters would allow PG&E to remain an investor-owned utility, 37% support government-run models and 28% had no opinion.

A state takeover with a side of municipalization

San Francisco state Sen. Scott Wiener this week introduced legislation that would turn PG&E into a publicly owned utility. Senate Bill 917 is modeled on a public-private partnership at Long Island Power Authority, owned by the state of New York. PG&E said its facilities are not for sale and pointed to Long Island’s substantial debt load and high electricity rates.

Wiener’s plan calls for establishing a state power authority, led by a governor-appointed board, to purchase the utility’s assets and then transition from investor to public ownership. The new entity would be called the Northern California Energy Utility District with a public

benefit corporation called Northern California Energy Services managing the day-to-day operations.

The bill would allow cities, such as San Francisco, to eventually fulfill plans for their own utilities.

“This is a dream a long time in coming,” San Francisco Supervisor Aaron Peskin said at Weiner’s press conference. “For 20 years, the leaders and the people of San Francisco County have been looking forward to public power. Now it has become a statewide issue and those of us who were at the forefront 20 years ago have clearly been vindicated.”

Resistance wouldn’t just come from the boardroom. Members of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, which represents utility workers, heckled Wiener’s press conference. At the Capitol, workers handed out flyers warning about job and pension losses.

A customer-owned ‘co-op’ PG&E

For months, San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo has been pushing to transition PG&E from investor ownership to customer ownership in the form of a cooperative, such as credit unions or mutual insurance companies. According to Liccardo, more than 900 cooperatives already serve 19 million customers in the U.S. The “co-op” would not require taxpayers to fork over tens of billions of dollars to buy out PG&E’s infrastructure. Instead, customers would be the owners, which would give them an incentive to make the grid safer.

“A customer-owned cooperative would encounter sharply lower capital costs than PG&E does today, because it would not need to pay dividends to shareholders, or federal taxes to Uncle Sam,” Liccardo wrote in an op-ed for CalMatters. “By saving billions in interest payments, a customer-owned company would devote more of its resources to improving the company’s infrastructure and service.”

While most co-ops were formed to deliver electricity to rural America, none exist on the scale Liccardo is proposing, said Michael Wara, director of the energy and climate program at Stanford Law School’s Woods Institute for the Environment. He notes there would be the same governance challenges to install a board with the necessary experience and expertise.

“There’s no silver bullet,” Wara said.

A radical third way: Treat wires like highways

In order to make PG&E safer, somebody – either investors, taxpayers or customers – will have to contribute significant sums of money to bury the most fire-prone power lines and do the necessary “hardening” of the electrical grid. PG&E’s rates are already high for the state, if not the country. And taxpayers are already paying for the firefighters who have to be deployed before a wildfire starts. For the upcoming wildfire season, Newsom said teams will be pre-positioned along PG&E’s transmission lines.

David Freeman, who headed the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and served for decades as general manager of the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, is proposing a radical third way: Take over all the poles and wires in California and treat them as a public good as the state does with roads, highways and bridges.

Freeman proposes creating a new state agency to take over all transmission systems in California and tasking it with making the infrastructure safe and reliable. The cost to taxpayers would be tremendous, perhaps to the tune of $1 trillion over 10 years, but he argues the cost of disrupting the state economy is even higher.

“This problem is more fundamental and bigger than the utilities,” Freeman said, referring to the climate change that is driving high winds and extreme temperatures now in summer and fall. “With all due respect, I think the governor and many other people in California are just lacking in vision. I think we’ve reached a fundamental tipping point. I think we need to be thinking of the electric delivery system as perhaps even more important than our highways.”

Utilities would continue to run the business of selling electricity. Freeman said treating the power lines like freeways would actually improve utilities’ finances because it would relieve both public and private utilities of strict liability for disaster damages — an ongoing issue that stems from a legal doctrine in state law known as “inverse condemnation.”

“I’m not saying this is an easy thing to do,” Freeman said. “But like Jack Kennedy said, we do some things because they’re hard. This problem is going to encompass everybody as time goes on.”

A refresher on PG&E resistance

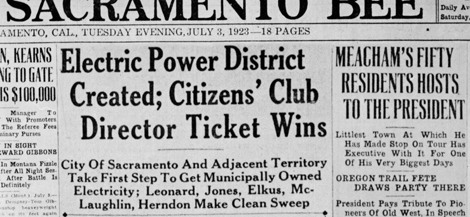

PG&E, which serves 16 million people in 48 counties, has long thwarted defectors. Nearly a century ago, the citizens of Sacramento voted to establish a community-owned, not-for-profit electricity service, and to get out of PG&E’s service territory. Decades of litigation ensued.

The Sacramento Bee’s investigative role in the fight is part of the paper’s lore now. Only in the late 1940s did the Sacramento Municipal Utilities District begin operations. More recently, PG&E sank more than $46 million into a failed campaign in 2010 on Proposition 16, which would have limited the ability of local governments to enter the electricity business. The initiative would have made municipal power authorities harder to establish by requiring cities and counties to win two-thirds approval before spending public money to start or join a public power agency.

Today, PG&E says it’s committed to exiting the bankruptcy process as quickly as possible. A white paper conducted by Concentric Energy Advisors outlines rebuttals to both municipalization and cooperatives, citing high debt and high customer rates.

“We remain convinced,” the company stated, “that a government or customer takeover is not the optimal solution that will address the challenges ahead and serve the long-run interests of all customers

in the communities we serve.”

What does the governor really want?

Newsom made multiple takeover threats during an appearance at the Public Policy Institute of California last week.

“PG&E, that company no longer exists,” Newsom said. “There’s gonna be a new company or the state of California takes it over and that new company is going to be transformed and in five or 10 years, I think that an IOU (investor-owned utility) potentially could make every one of us proud and could be a model for the rest of the nation if we do our job.”

What the governor is specifically demanding are significant changes within PG&E — namely a more qualified and independent board of directors made up of a majority of Californians; a way for the state to step in in extreme conditions; and for shareholders to give up some of their interests so the company has more capital to focus on safety. As things stand, Newsom says PG&E’s reorganization plan uses a combination of debt and securitization that leaves it with little financing room for making billions of dollars in safety investments.

It’s not clear if PG&E’s latest offer to turn over some board seats and name directors with more safety expertise, which follows weeks of closed-door talks with Newsom’s lead negotiators, is enough to appease the governor.

Time is running short. PG&E doesn’t just need to reemerge by June 30 to tap $21 billion in state financing. Sometime in July, it will lose its 18-month exclusive right to propose a reorganization plan in bankruptcy court. In that unlikely scenario, the court could look to competing reorganization plans from wildfire victims to bondholders.

And, of course, there’s another looming deadline.

“Fire season is coming,” noted Ellias, the law professor. “And it would be really good if this company is out of bankruptcy by then.”