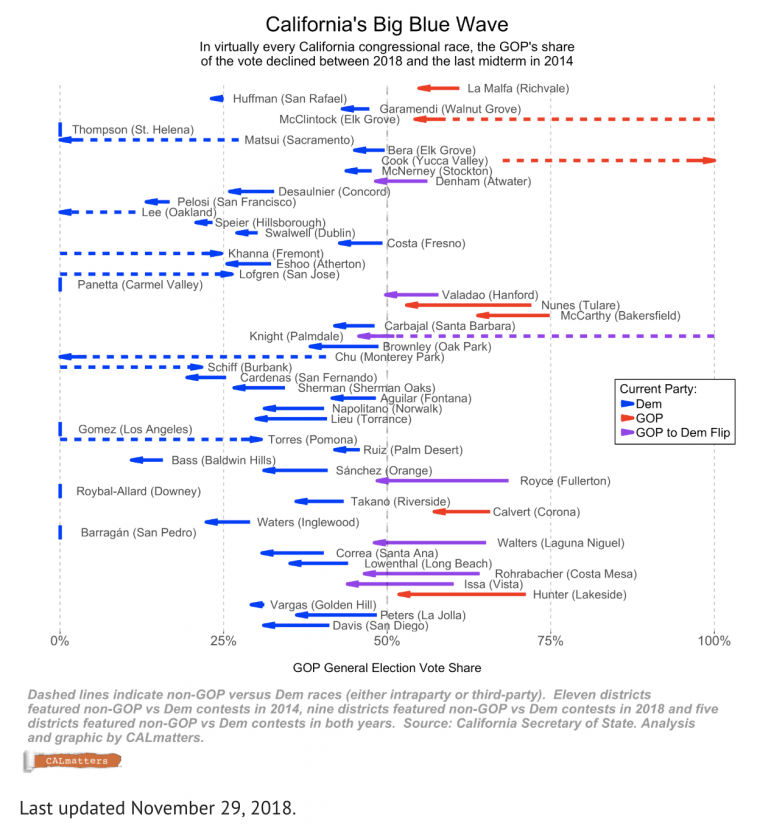

No doubt you’ve heard about the blue wave: the electoral tsunami of left-of-center enthusiasm that slammed into California on election day, flipping seven of 14 GOP-held congressional districts to the Democrats. But that was just the wave’s frothy cap.

For every single congressional district that featured a face-off between a Democrat and Republican in this midterm and the last, the California electorate shifted further blue. The average Democratic gain was 9 percentage points since 2014.

As the sea of leftward pointing arrows above shows, Democrats amassed a larger share of the vote in all but five districts this year, including several that stayed in GOP hands. In 2014, for example, Central Valley Republican Rep. Devin Nunes won 72 percent of the vote. This year (at last count) he snagged a slim majority of 53 percent.

As the sea of leftward pointing arrows above shows, Democrats amassed a larger share of the vote in all but five districts this year, including several that stayed in GOP hands. In 2014, for example, Central Valley Republican Rep. Devin Nunes won 72 percent of the vote. This year (at last count) he snagged a slim majority of 53 percent.

There was a leftward shift in most solidly blue districts this year too. Take Rep. Ted Lieu in Torrence. In 2014, he won his seat by a little less than 60 percent of the vote, leaving 41 percent of the vote for his Republican opponent. This year, he won by an even more resounding 70 percent.

The only districts that proved immune to the national wave of anti-Trump energy that swept the country—and swept Democrats back into the House majority—were districts where a Democrat and Republican did not square off against one another in one of the two election years (those districts are indicated by dashed lines above).

In California’s 8th congressional district, which covers much of the state’s eastern desert, two Republicans, Rep. Paul Cook and former Assemblyman Tim Donnelly, made it into the top two. That sole GOP shutout in the primary allowed the Republicans to rack up 100 percent of the vote there this year.

The other exceptions are true blue enclaves such as Burbank or San Jose where Republicans were shutout in 2014. This year, Republican candidates in those districts were able to improve upon their party’s prior vote share of 0 percent—but only modestly.

Democratic districts such as the one based in San Pedro didn’t see a Republican compete in either year. Not much room for Democratic improvement there.

If the graphic above looks familiar, it’s because we’ve run a similar version before. In a post from earlier this summer, we showed how the share of the vote going towards Republican candidates in the June primary fell dramatically in most seats between 2014 and 2018. The title of that article was “California’s Blue Wave watch: Why this graphic should worry Republicans.”

In retrospect, that sounds about right.